Deinonychus

Ostrom noted the small body, sleek, horizontal posture, ratite-like spine, and especially the enlarged raptorial claws on the feet, which suggested an active, agile predator.

[5][6] Additionally, teeth found in the Arundel Clay Facies (mid-Aptian), of the Potomac Formation on the Atlantic Coastal Plain of Maryland may be assigned to the genus.

"[8] He informally called the animal "Daptosaurus agilis" and made preparations for describing it and having the skeleton, specimen AMNH 3015, put on display, but never finished this work.

[9] Brown brought back from the Cloverly Formation the skeleton of a smaller theropod with seemingly oversized teeth that he informally named "Megadontosaurus".

[9] A little more than thirty years later, in August 1964, paleontologist John Ostrom led an expedition from Yale's Peabody Museum of Natural History which discovered more skeletal material near Bridger.

Ostrom's skeletal reconstruction of Deinonychus included a very unusual pelvic bone—a pubis that was trapezoidal and flat, unlike that of other theropods, but which was the same length as the ischium and which was found right next to it.

[12] In that same year, another specimen of Deinonychus, MCZ 4371, was discovered and excavated in Montana by Steven Orzack during a Harvard University expedition headed by Farish Jenkins.

Several long, thin bones identified on the blocks as ossified tendons (structures that helped stiffen the tail of Deinonychus) turned out to actually represent gastralia (abdominal ribs).

[24][25] When conducting studies of such areas as the range of motion in the forelimbs, paleontologists like Phil Senter have taken the likely presence of wing feathers (as present in all known dromaeosaurs with skin impressions) into consideration.

Additional Deinonychus skull material and closely related species found with good three-dimensional preservation[31] show that the palate was more vaulted than Ostrom thought, making the snout far narrower, while the jugals flared broadly, giving greater stereoscopic vision.

[25] Deinonychus antirrhopus is one of the best known dromaeosaurid species,[34] and also a close relative of the smaller Velociraptor, which is found in younger, Late Cretaceous-age rock formations in Central Asia.

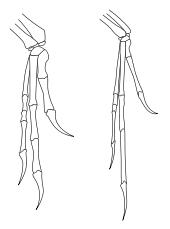

This proposal is based primarily on comparisons between the morphology and proportions of the feet and legs of dromaeosaurs to several groups of extant birds of prey with known predatory behaviors.

Fowler found that the feet and legs of dromaeosaurs most closely resemble those of eagles and hawks, especially in terms of having an enlarged second claw and a similar range of grasping motion.

[46] A 2010 study by Paul Gignac and colleagues attempted to estimate the bite force based directly on newly discovered Deinonychus tooth puncture marks in the bones of a Tenontosaurus.

They found the bite force of Deinonychus to be between 4,100 and 8,200 newtons, greater than living carnivorous mammals including the hyena, and equivalent to a similarly-sized alligator.

It is also suggested in these findings that Deinonychus may have fed by using neck-driven pullback movements to dismember carcasses when feeding, akin to modern varanid lizards.

[45] Biomechanical studies by Ken Carpenter in 2002 confirmed that the most likely function of the forelimbs in predation was grasping, as their great lengths would have permitted longer reach than for most other theropods.

The function of the fingers would also have been limited by feathers; for example, only the third digit of the hand could have been employed in activities such as probing crevices for small prey items, and only in a position perpendicular to the main wing.

[26] Alan Gishlick, in a 2001 study of Deinonychus forelimb mechanics, found that even if large wing feathers were present, the grasping ability of the hand would not have been significantly hindered; rather, grasping would have been accomplished perpendicular to the wing, and objects likely would have been held by both hands simultaneously in a "bear hug" fashion, findings which have been supported by the later forelimb studies by Carpenter and Senter.

Therefore, Ostrom concluded that the legs of Deinonychus represented a balance between running adaptations needed for an agile predator, and stress-reducing features to compensate for its unique foot weapon.

[13] In his 1981 study of Canadian dinosaur footprints, Richard Kool produced rough walking speed estimates based on several trackways made by different species in the Gething Formation of British Columbia.

[68] In a 2015 paper, it was reported after further analysis of immature fossils that the open and mobile nature of the shoulder joint might have meant that young Deinonychus were capable of some form of flight.

They dismissed the idea that the egg had been a meal for the theropod, noting that the fragments were sandwiched between the belly ribs and forelimb bones, making it impossible that they represented contents of the animal's stomach.

It is possible that this represents brooding or nesting behavior in Deinonychus similar to that seen in the related troodontids and oviraptorids, or that the egg was in fact inside the oviduct when the animal died.

[8] A study published in November 2018 by Norell, Yang and Wiemann et al., indicates that Deinonychus laid blue eggs, likely to camouflage them as well as creating open nests.

The study also indicates that Deinonychus and other dinosaurs that created open nests likely represent an origin of color in modern bird eggs as an adaptation both for recognition and camouflage against predators.

Modern archosaurs (birds and crocodiles) and Komodo dragons typically display little cooperative hunting; instead, they are usually either solitary hunters, or are drawn to previously killed carcasses, where much conflict occurs between individuals of the same species.

However, the authors still suggest gregariousness in some dromaeosaurids such as Deinonychus and they probably practiced ratite-like parental care, instead of a complete agnostic relationship as seen in Komodo dragons, due to the lack of spatial separation of juveniles and adults.

In Oklahoma, the ecosystem of Deinonychus also included the large theropod Acrocanthosaurus, the huge sauropod Sauroposeidon, the crocodilians Goniopholis and Paluxysuchus, and the gar Lepisosteus.

Crichton had met with John Ostrom several times during the writing process to discuss details of the possible range of behaviors and life appearance of Deinonychus.