Deism

Deism (/ˈdiːɪzəm/ DEE-iz-əm [1][2] or /ˈdeɪ.ɪzəm/ DAY-iz-əm; derived from the Latin term deus, meaning "god")[3][4] is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology[5] that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation of the natural world are exclusively logical, reliable, and sufficient to determine the existence of a Supreme Being as the creator of the universe.

[11] More simply stated, Deism is the belief in the existence of God—often, but not necessarily, an impersonal and incomprehensible God who does not intervene in the universe after creating it,[8][12] solely based on rational thought without any reliance on revealed religions or religious authority.

[14] Since the 17th century and during the Age of Enlightenment, especially in 18th-century England, France, and North America,[15] various Western philosophers and theologians formulated a critical rejection of the several religious texts belonging to the many organized religions, and began to appeal only to truths that they felt could be established by reason as the exclusive source of divine knowledge.

[20] The 3rd-century Christian theologian and philosopher Clement of Alexandria explicitly mentioned persons who believed that God was not involved in human affairs, and therefore led what he considered a licentious life.

[23][24] In the 9th–10th century CE, the Ashʿarī school developed as a response to the Muʿtazila, founded by the 10th-century Muslim scholar and theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī.

[25] This position was opposed by the Māturīdī school;[26] according to its founder, the 10th-century Muslim scholar and theologian Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī, human reason is supposed to acknowledge the existence of a creator deity (bāriʾ) solely based on rational thought and independently from divine revelation.

The first two-thirds of his book De Veritate (On Truth, as It Is Distinguished from Revelation, the Probable, the Possible, and the False) are devoted to an exposition of Herbert's theory of knowledge.

[31] The appearance of John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) marks an important turning-point and new phase in the history of English Deism.

[35] Following Locke's successful attack on innate ideas, Tindal's "Bible" redefined the foundation of Deist epistemology as knowledge based on experience or human reason.

[36][37] "Constructive" assertions—assertions that deist writers felt were justified by appeals to reason and features of the natural world (or perhaps were intuitively obvious or common notions)—included:[38][39] "Critical" assertions—assertions that followed from the denial of revelation as a valid source of religious knowledge—were much more numerous, and included: A central premise of Deism was that the religions of their day were corruptions of an original religion that was pure, natural, simple, and rational.

Humanity lost this original religion when it was subsequently corrupted by priests who manipulated it for personal gain and for the class interests of the priesthood,[41] and encrusted it with superstitions and "mysteries"—irrational theological doctrines.

Lord Herbert of Cherbury and William Wollaston[46] held that souls exist, survive death, and in the afterlife are rewarded or punished by God for their behavior in life.

Enlightenment philosophers under the influence of Newtonian science tended to view the universe as a vast machine, created and set in motion by a creator being, that continues to operate according to natural law without any divine intervention.

[53] In Waring's words: The clear reasonableness of natural religion disappeared before a semi-historical look at what can be known about uncivilized man— "a barbarous, necessitous animal," as Hume termed him.

And the history of religion was not, as the deists had implied, retrograde; the widespread phenomenon of superstition was caused less by priestly malice than by man's unreason as he confronted his experience.

English Deism was an important influence on the thinking of Thomas Jefferson and the principles of religious freedom asserted in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Other Founding Fathers who were influenced to various degrees by Deism were Ethan Allen,[55] Benjamin Franklin, Cornelius Harnett, Gouverneur Morris, Hugh Williamson, James Madison, and possibly Alexander Hamilton.

[58][59][60] In his Autobiography, Franklin wrote that as a young man "Some books against Deism fell into my hands; they were said to be the substance of sermons preached at Boyle's lectures.

"[61][62] Like some other Deists, Franklin believed that, "The Deity sometimes interferes by his particular Providence, and sets aside the Events which would otherwise have been produc'd in the Course of Nature, or by the Free Agency of Man,"[63] and at the Constitutional Convention stated that "the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth—that God governs in the affairs of men.

[65] Thomas Paine is especially noteworthy both for his contributions to the cause of the American Revolution and for his writings in defense of Deism, alongside the criticism of Abrahamic religions.

He commanded the spirit of victory to direct the hand of the faithful French, and in a few hours the aristocrats received the attack which we prepared, the wicked ones were destroyed and liberty was avenged.

[82] According to Taylor, by the early 19th century this Deism-mediated exclusive humanism developed as an alternative to Christian faith in a personal God and an order of miracles and mystery.

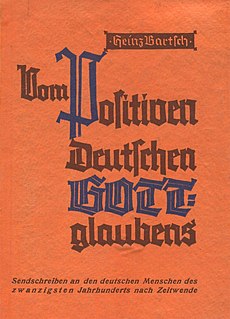

[85][86] The 1943 Philosophical Dictionary defined Gottgläubig as: "official designation for those who profess a specific kind of piety and morality, without being bound to a church denomination, whilst however also rejecting irreligion and godlessness.

[84] Those who left the churches were designated as Gottgläubige ("believers in God"), a term officially recognised by the Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick on 26 November 1936.

[84] The term "dissident", which some church leavers had used up until then, was associated with being "without belief" (glaubenslos), whilst most of them emphasized that they still believed in a God, and thus required a different word.

[97][98][99][100][101][102][103] The report's publication generated large-scale controversy in the Turkish press and society at large, as well as amongst conservative Islamic sects, Muslim clerics, and Islamist parties in Turkey.

[108] Edison was labeled an atheist for those remarks, and although he did not allow himself to be drawn into the controversy publicly, he clarified himself in a private letter: You have misunderstood the whole article, because you jumped to the conclusion that it denies the existence of God.

All the article states is that it is doubtful in my opinion if our intelligence or soul or whatever one may call it lives hereafter as an entity or disperses back again from whence it came, scattered amongst the cells of which we are made.

"[109] The 2001 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) report estimated that between 1990 and 2001 the number of self-identifying Deists grew from 6,000 to 49,000, representing about 0.02% of the U.S. population at the time.

[111] The term "ceremonial deism" was coined in 1962 and has been used since 1984 by the Supreme Court of the United States to assess exemptions from the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, thought to be expressions of cultural tradition and not earnest invocations of a deity.