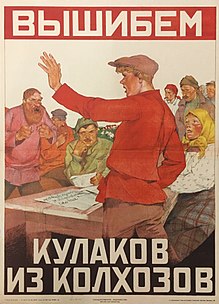

Dekulakization

They posed a danger to Stalin's collectivization efforts, which sought to end private land ownership and centralize agricultural production under state supervision.

Lenin sent several other telegrams to Penza demanding harsher measures in order to fight the kulaks, kulak-supporting peasants and Left SR insurrectionists.

"[10] The Politburo of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) formalized the decision in a resolution titled "On measures for the elimination of kulak households in districts of comprehensive collectivization" on 30 January 1930.

[11] In fact, a high-ranking member of the OGPU (the secret police) shared his vision for a new penal system that would establish villages in the northern Soviet Union that could specialize in extracting natural resources and help Stalin's industrialization.

[12] An OGPU secret-police functionary, Yefim Yevdokimov (1891–1939), played a major role in organizing and supervising the round-up of kulaks and their mass executions.

His adversary, Leon Trotsky, condemned the "liquidation of the kulaks" in 1930 as a "monstrosity" and had urged the Politbureau during the intra-party struggle to raise taxation on wealthier farmers and encourage farm labourers along with poor peasants to form collective farms on a voluntary basis with state resources allocated to agricultural machinery, fertilizers, credit and agronomic assistance.

The actions taken against the kulaks were a part of a larger effort to end private land ownership and centralize agricultural output under state control, which had significant repercussions for Soviet society and the peasantry.

Families in their entirety, including children of all ages, were frequently deported to distant parts of the nation or sent to camps for forced labor.

Children were "put into homes or orphanages and separated from their families as part of the dekulakization policies in the Soviet Union during the 1930s," according to historian Lynne Viola.

During the dekulakization effort, they had to deal with a variety of difficulties, such as losing their homes and belongings, being separated from their families, as well as the danger of forced labor and violence, both physical and sexual.

[18] Sociologist Michael Mann described the Soviet attempt to collectivize and liquidate perceived class enemies as fitting his proposed category of classicide.

The official goal of kulak liquidation came without precise instructions, and encouraged local leaders to take radical action, which resulted in physical elimination.

The New Economic Policy (NEP), which was implemented by the Soviet secret police known as the Cheka, gave rise to the phrase "liquidation" in the early 1920s.

The liquidation campaign was directed at those who were thought to pose a threat to the Soviet government's attempt to consolidate its control, such as former Tsarist regime members, bourgeois intellectuals, and other deemed adversaries of the state.

The liquidation campaign, which included arrests, executions, and other acts of repression, was part of a larger initiative to quell dissent and solidify the Soviet Communist Party's power.

The liquidation campaign was largely focused on the political opponents of the Bolshevik government in the early years of the Soviet Union.

The campaign's objectives, however, changed in the late 1920s to include perceived adversaries of the Soviet economy, such as the so-called "kulaks" or prosperous peasant farmers.

The drive to eliminate the kulaks was a component of a larger collectivization strategy that attempted to centralize agricultural output under state control.

The liquidation campaign, which lasted through the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s, was a crucial component of the Soviet Union's endeavor to achieve complete control over all facets of society.

Although it is difficult to assess the scope of the campaign and the number of casualties, historians estimate that tens of thousands of individuals were put to death or imprisoned during this time.

The Soviet government targeted the so-called "kulaks" or wealthy peasant farmers, who were viewed as a threat to the collectivization of agriculture, during the most intense era of liquidation, which took place in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The phrase was not specifically applied to Soviet politics in its earlier usage; rather, it referred to the act of removing barriers or resolving issues.