Dementia praecox

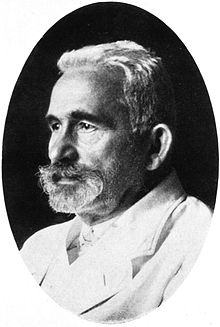

German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) popularised the term dementia praecox in his first detailed textbook descriptions of a condition that eventually became a different disease concept later relabeled as schizophrenia.

[8] By the eighteenth century, at the period when the term entered into European medical discourse, clinical concepts were added to the vernacular understanding such that dementia was now associated with intellectual deficits arising from any cause and at any age.

[10] This holds that dementia is understood in terms of criteria relating to aetiology, age and course which excludes former members of the family of the demented such as adults with acquired head trauma or children with cognitive deficits.

[11] The term démence précoce was used in passing to describe the characteristics of a subset of young mental patients by the French physician Bénédict Augustin Morel in 1852 in the first volume of his Études cliniques.

[13] Morel, whose name will be forever associated with religiously inspired concept of degeneration theory in psychiatry, used the term in a descriptive sense and not to define a specific and novel diagnostic category.

"[17] Morel described several psychotic disorders that ended in dementia, and as a result he may be regarded as the first alienist or psychiatrist to develop a diagnostic system based on presumed outcome rather than on the current presentation of signs and symptoms.

[20] This latter notion, derived from the Belgian psychiatrist Joseph Guislain (1797–1860), held that the variety of symptoms attributed to mental illness were manifestations of a single underlying disease process.

[23] Although with the passage of time this work would prove profoundly influential, when it was published it was almost completely ignored by German academia despite the sophisticated and intelligent disease classification system which it proposed.

[24] In this book Kahlbaum categorized certain typical forms of psychosis (vesania typica) as a single coherent type based upon their shared progressive nature which betrayed, he argued, an ongoing degenerative disease process.

He was accompanied by his younger assistant, Ewald Hecker (1843–1909), and during a ten-year collaboration they conducted a series of research studies on young psychotic patients that would become a major influence on the development of modern psychiatry.

An additional feature of the clinical method was that the characteristic symptoms that define syndromes should be described without any prior assumption of brain pathology (although such links would be made later as scientific knowledge progressed).

[28] Upon his appointment to a full professorship in psychiatry at the University of Dorpat (now Tartu, Estonia) in 1886, Kraepelin gave an inaugural address to the faculty outlining his research programme for the years ahead.

[29] It has also been suggested that Kraepelin's decision to accept the Dorpat post was informed by the fact that there he could hope to gain experience with chronic patients and this, it was presumed, would facilitate the longitudinal study of mental illness.

[30] Understanding that objective diagnostic methods must be based on scientific practice, Kraepelin had been conducting psychological and drug experiments on patients and normal subjects for some time when, in 1891, he left Dorpat and took up a position as professor and director of the psychiatric clinic at Heidelberg University.

[32]The fourth edition of his textbook, Psychiatrie, published in 1893, two years after his arrival at Heidelberg, contained some impressions of the patterns Kraepelin had begun to find in his index cards.

[35] Though his work and that of his research associates had revealed a role for heredity, Kraepelin realized nothing could be said with certainty about the aetiology of dementia praecox, and he left out speculation regarding brain disease or neuropathology in his diagnostic descriptions.

Nevertheless, from the 1896 edition onwards Kraepelin made clear his belief that poisoning of the brain, "auto-intoxication," probably by sex hormones, may underlie dementia praecox – a theory also entertained by Eugen Bleuler.

[36] Kraepelin, recognizing dementia praecox in Chinese, Japanese, Tamil and Malay patients, suggested in the eighth edition of Psychiatrie that, "we must therefore seek the real cause of dementia praecox in conditions which are spread all over the world, which thus do not lie in race or in climate, in food or in any other general circumstance of life..."[37] Kraepelin had experimented with hypnosis but found it wanting, and disapproved of Freud's and Jung's introduction, based on no evidence, of psychogenic assumptions to the interpretation and treatment of mental illness.

He argued that, without knowing the underlying cause of dementia praecox or manic-depressive illness, there could be no disease-specific treatment, and recommended the use of long baths and the occasional use of drugs such as opiates and barbiturates for the amelioration of distress, as well as occupational activities, where suitable, for all institutionalized patients.

Based on his theory that dementia praecox is the product of autointoxication emanating from the sex glands, Kraepelin experimented, without success, with injections of thyroid, gonad and other glandular extracts.

[37] In the early years of the twentieth century the twin pillars of the Kraepelinian dichotomy, dementia praecox and manic depressive psychosis, were assiduously adopted in clinical and research contexts among the Germanic psychiatric community.

[37] German-language psychiatric concepts were always introduced much faster in America (than, say, Britain) where émigré German, Swiss and Austrian physicians essentially created American psychiatry.

Swiss-émigré Adolf Meyer (1866–1950), arguably the most influential psychiatrist in America for the first half of the 20th century, published the first critique of dementia praecox in an 1896 book review of the 5th edition of Kraepelin's textbook.

[38][39] Both dementia praecox (in its three classic forms) and "manic-depressive psychosis" gained wider popularity in the larger institutions in the eastern United States after being included in the official nomenclature of diseases and conditions for record-keeping at Bellevue Hospital in New York City in 1903.

Due to the influence of alienists such as Adolf Meyer, August Hoch, George Kirby, Charles Macphie Campbell, Smith Ely Jelliffe and William Alanson White, psychogenic theories of dementia praecox dominated the American scene by 1911.