Demographic history of Kosovo

[8] The decrease in material finds corresponds to the effects which the plague of Justinian probably had throughout the Balkans as millions of people died and many regions became depopulated.

According to historian Richard J. Crampton, the development of Old Church Slavonic literacy during the 10th century had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into the Byzantine culture, which promoted the formation of a distinct Bulgarian identity in that area.

In 1072 an unsuccessful rebellion led by local Bulgarian landlord Georgi Voiteh arose in the area and in 1072 in Prizren he was crowned "Tsar of Bulgaria".

Chrysobulls related to tax rights for Orthodox monasteries form the vast majority of the existing sources for the available demographics of Kosovo in the 14th century.

[27] Among the settlements over which Dečani held tax rights in modern-day Kosovo, find Serbs living alongside Albanians and Vlachs.

In the golden bull of Stefan Dušan (1348) a total of nine Albanian villages are cited within the vicinity of Prizren among the communities which were under tax obligations.

[42] Successive persecutions of Serbs by the Ottomans in the southern Balkans resulted in migrations to areas under the control of the Habsburg monarchy, in particular during the Great Turkish War of 1683–1699.

The Ottoman statistics are regarded as unreliable, as the empire counted its citizens by religion rather than nationality, using birth records rather than surveys of individuals.

[52] Apart from the Lab region, sizeable numbers of Albanian refugees were resettled in other parts of northern Kosovo alongside the new Ottoman-Serbian border.

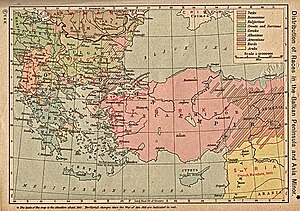

[59] In the late Ottoman period, Kosovo vilayet contained a diverse population of Muslim Albanians and Orthodox Serbs that was split along religious and ethnic lines.

[60] Muslim Bosniaks whose native language was Slavic formed a sizable number of Kosovo vilayet's population and were concentrated mainly in Yenipazar sanjak.

[61] In the northern half of Kosovo vilayet Orthodox Serbs were the largest Christian group and formed a majority within the eastern areas.

[61] Ottoman provincial records for 1887 estimated that Albanians formed more than half of Kosovo vilayet's population concentrated in the sanjaks of İpek, Prizren and Priştine.

[64] Paolo Maggiolini attributes the decline of the Christian population to failure of the 1878 uprising, which was used by the Ottoman authorities to justify forced conversions and expulsions of the Catholic and Orthodox communities in Kosovo.

[67]Because the process of religious conversion was violent and forced, Kosovo Albanians were also only nominally Muslims, with converts becoming fully only Islamicized after several generations.

[73] Beginning from 1912, Montenegro initiated its attempts at colonisation and enacted a law on the process during 1914 that aimed at expropriating 55,000 hectares of Albanian land and transferring it to 5,000 Montenegrin settlers.

[75] Serbia undertook measures for colonisation by enacting a decree aimed at colonists within "newly liberated areas" that offered 9 hectares of land to families.

[87][96] To date, access is unavailable to the Turkish Foreign Ministry archive regarding this issue and as such the total numbers of Albanians arriving to Turkey during the interwar period are difficult to determine.

[97][91][98] The majority of Montenegrin and Serb settlers consisting of bureaucrats and dobrovoljac fled from Kosovo to Axis occupied Serbia or Montenegro.

[103] Following the Second World War and establishment of communist rule in Yugoslavia, the colonisation programme was discontinued, as President Tito wanted to avoid sectarian and ethnic conflicts.

[104] Tito enacted a temporary decree in March 1945 that banned the return of colonists, which included some Chetniks and the rest that left during the war seeking refuge.

[105] A small proportion of the previous colonist population came back to Kosovo and repossessed land, with a greater part of their number (4,000 families) later leaving for other areas of Yugoslavia.

The majority of these post-war migrants were family members of Albanians settled in Kosovo during the Second World War by the Italian occupation force.

[108][109] In 1953, an agreement was reached between Tito and Mehmet Fuat Köprülü, the foreign minister of Turkey that promoted the emigration of Albanians to Anatolia.

[108] From 1961 to 1981, the ethnic Albanian population of Kosovo almost doubled as a result of high birth rates, illegal migration from communist Albania and rapid urbanisation.

[113] As such, the state made available loans for building apartments and homes along with employment opportunities for Montenegrins and Serbs that chose to relocate to the region.

[113] At the time, the government under President Slobodan Milošević pursued colonisation amidst a situation of financial difficulties and limited resources.

[113] Laws were passed by the parliament of Serbia that sought to change the power balance in Kosovo relating to the economy, demography and politics.

[115] It outlined government benefits for Serbs who desired to go and live in Kosovo with loans to build homes or purchase other dwellings and offered free plots of land.

[116] In 1995, the government attempted to alter the ethnic balance of the region through the planned resettlement of 100,000, later reduced to 20,000 Serbian refugees from Krajina in Croatia to Kosovo.