Demographic transition

[1] However, the existence of some kind of demographic transition is widely accepted because of the well-established historical correlation linking dropping fertility to social and economic development.

Scholars also debate to what extent various proposed and sometimes interrelated factors such as higher per capita income, lower mortality, old-age security, and rise of demand for human capital are involved.

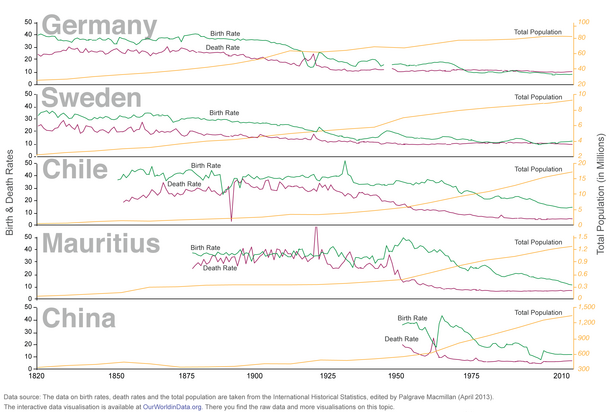

Many countries such as China, Brazil and Thailand have passed through the Demographic Transition Model (DTM) very quickly due to fast social and economic change.

[1] Family planning and contraception were virtually nonexistent; therefore, birth rates were essentially only limited by the ability of women to bear children.

Children contributed to the economy of the household from an early age by carrying water, firewood, and messages, caring for younger siblings, sweeping, washing dishes, preparing food, and working in the fields.

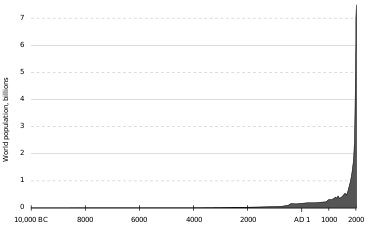

During the second half of the twentieth century less-developed countries entered Stage Two, creating the worldwide rapid growth of number of living people that has demographers concerned today.

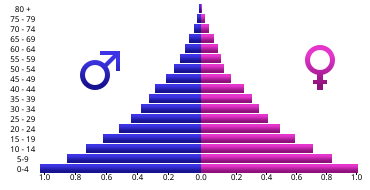

Hence, the age structure of the population becomes increasingly youthful and start to have big families and more of these children enter the reproductive cycle of their lives while maintaining the high fertility rates of their parents.

Countries that have witnessed a fertility decline of over 50% from their pre-transition levels include: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Panama, Jamaica, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Lebanon, South Africa, India, Saudi Arabia, and many Pacific islands.

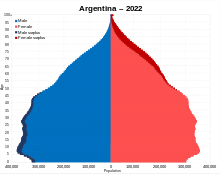

Countries that were at this stage (total fertility rate between 2.0 and 2.5) in 2015 include: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cabo Verde, El Salvador, Faroe Islands, Grenada, Guam, India, Indonesia, Kosovo, Libya, Malaysia, Maldives, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, New Caledonia, Nicaragua, Palau, Peru, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Tunisia, Turkey, and Venezuela.

The global data no longer support the suggestion that fertility rates tend to broadly rise at very high levels of national development.

[30][31] Jane Falkingham of Southampton University has noted that "We've actually got population projections wrong consistently over the last 50 years... we've underestimated the improvements in mortality... but also we've not been very good at spotting the trends in fertility.

This stage of the transition is often referred to as the golden age, and is typically when populations see the greatest advancements in living standards and economic development.

[citation needed] Scientific discoveries and medical breakthroughs did not, in general, contribute importantly to the early major decline in infectious disease mortality.

The uniqueness of the French case arises from its specific demographic history, its historic cultural values, and its internal regional dynamics.

Several interrelated reasons account for such singularities, in particular the impact of pro-family policies accompanied by greater unmarried households and out-of-wedlock births.

An effective, often authoritarian, local administrative system can provide a framework for promotion and services in health, education, and family planning.

[41] Cha (2007) analyzes a panel data set to explore how industrial revolution, demographic transition, and human capital accumulation interacted in Korea from 1916 to 1938.

The interwar agricultural depression aggravated traditional income inequality, raising fertility and impeding the spread of mass schooling.

Landlordism collapsed in the wake of de-colonization, and the consequent reduction in inequality accelerated human and physical capital accumulation, hence leading to growth in South Korea.

Both supporters and critics of the theory hold to an intrinsic opposition between human and "natural" factors, such as climate, famine, and disease, influencing demography.

They also suppose a sharp chronological divide between the precolonial and colonial eras, arguing that whereas "natural" demographic influences were of greater importance in the former period, human factors predominated thereafter.

Sparsely populated interior of the country allowed ample room to accommodate all the "excess" people, counteracting mechanisms (spread of communicable diseases due to overcrowding, low real wages and insufficient calories per capita due to the limited amount of available agricultural land) which led to high mortality in the Old World.

In New Orleans, mortality remained so high (mainly due to yellow fever) that the city was characterized as the "death capital of the United States" – at the level of 50 per 1000 population or higher – well into the second half of the 19th century.

Some trends in waterborne bacterial infant mortality are also disturbing in countries like Malawi, Sudan and Nigeria; for example, progress in the DTM clearly arrested and reversed between 1975 and 2005.

[55]: 181 [55][56][57] SDT addressed the changes in the patterns of sexual and reproductive behavior which occurred in North America and Western Europe in the period from about 1963, when the birth control pill and other cheap effective contraceptive methods such as the IUD were adopted by the general population, to the present.

[59] In 2015, Nicholas Eberstadt, political economist at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, described the Second Demographic Transition as one in which "long, stable marriages are out, and divorce or separation are in, along with serial cohabitation and increasingly contingent liaisons.

"[60] S. Philip Morgan thought future development orientation for SDT is Social demographers should explore a theory that is not based on stages, a theory that does not set a single line, a development path for some final stage—in the case of SDT, a hypothesis that looks like the advanced Western countries that most embrace postmodern values.

The Latin American countries experienced a major growth in pre-marital cohabitation in which the upper social classes were catching up with pre-existing higher levels among the less educated and some ethnic groups.

The opposite holds for Asian patriarchal societies which have traditionally strong rules of arranged endogamous marriage and male dominance.

In industrialised East Asian societies a major postponement of union formation and parenthood took place, leading to an expansion of numbers of singles and to very low levels of sub-replacement fertility.

Note the vertical axis is logarithmic and represents millions of people.

Pink line: crude death rate (CDR), green line: (crude) birth rate (CBR), yellow line: population.