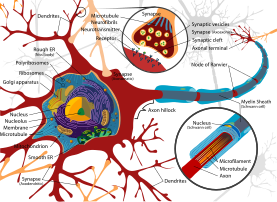

Dendrite

Dendrites play a critical role in integrating these synaptic inputs and in determining the extent to which action potentials are produced by the neuron.

To generate an action potential, many excitatory synapses have to be active at the same time, leading to strong depolarization of the dendrite and the cell body (soma).

Unipolar neurons, typical for insects, have a stalk that extends from the cell body that separates into two branches with one containing the dendrites and the other with the terminal buttons.

[4] The term dendrites was first used in 1889 by Wilhelm His to describe the number of smaller "protoplasmic processes" that were attached to a nerve cell.

[9] German anatomist Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters is generally credited with the discovery of the axon by distinguishing it from the dendrites.

Swiss Rüdolf Albert von Kölliker and German Robert Remak were the first to identify and characterize the axonal initial segment.

Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley also employed the squid giant axon (1939) and by 1952 they had obtained a full quantitative description of the ionic basis of the action potential, leading to the formulation of the Hodgkin–Huxley model.

[13] Experiments done in vitro and in vivo have shown that the presence of afferents and input activity per se can modulate the patterns in which dendrites differentiate.

[14] Little is known about the process by which dendrites orient themselves in vivo and are compelled to create the intricate branching pattern unique to each specific neuronal class.

A complex array of extracellular and intracellular cues modulates dendrite development including transcription factors, receptor-ligand interactions, various signaling pathways, local translational machinery, cytoskeletal elements, Golgi outposts and endosomes.

Other important transcription factors involved in the morphology of dendrites include CUT, Abrupt, Collier, Spineless, ACJ6/drifter, CREST, NEUROD1, CREB, NEUROG2 etc.

This integration is both temporal, involving the summation of stimuli that arrive in rapid succession, as well as spatial, entailing the aggregation of excitatory and inhibitory inputs from separate branches.

Dendrite radius has notable effects on resistance to electrical current, which in turn affects conduction time and speed.

[22][23] Dendrites release a multitude of neuroactive substances that are not confined to specific neurotransmitter class, signaling molecule, or brain area.

In the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial peptide system, oxytocin and vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone or ADH), are notable neuropeptides that are released from the dendrites of magnocellular neurosecretory cells (MCNs), allowing them to quickly enter the bloodstream.

Loss of dopamine from in the nigrostriatal pathway affects neuronal activity from the basal ganglia, therefore playing a role in the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's.

Dendritic release of oxytocin, ADH and dopamine have been found to have both autocrine and paracrine effects on the neuron itself (and nearby glia), as well as on afferent nerve terminals[24].

In females, the dendritic structure can change as a result of physiological conditions induced by hormones during periods such as pregnancy, lactation, and following the estrous cycle.