Dendritic spine

Dendritic spines serve as a storage site for synaptic strength and help transmit electrical signals to the neuron's cell body.

In addition to spines providing an anatomical substrate for memory storage and synaptic transmission, they may also serve to increase the number of possible contacts between neurons.

[4] Excitatory axon proximity to dendritic spines is not sufficient to predict the presence of a synapse, as demonstrated by the Lichtman lab in 2015.

Formation of this "spine apparatus" depends on the protein synaptopodin and is believed to play an important role in calcium handling.

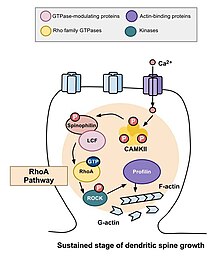

The role of Rho family of GTPases and its effects in the stability of actin and spine motility[9] has important implications for memory.

Rho family of GTPases makes significant contributions to the process that stimulates actin polymerization, which in turn increases the size and shape of the spine.

[11] Because changes in the shape and size of dendritic spines are correlated with the strength of excitatory synaptic connections and heavily depend on remodeling of its underlying actin cytoskeleton,[12] the specific mechanisms of actin regulation, and therefore the Rho family of GTPases, are integral to the formation, maturation, and plasticity of dendritic spines and to learning and memory.

One of the major Rho GTPases involved in spine morphogenesis is RhoA, a protein that also modulates the regulation and timing of cell division.

[13] A study conducted by Murakoshi et al. in 2011 implicated the Rho GTPases RhoA and Cdc42 in dendritic spine morphogenesis.

Both GTPases were quickly activated in single dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus during structural plasticity brought on by long-term potentiation stimuli.

[14] Calcium influx into the cell through NMDA receptors binds to calmodulin and activates the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases II (CaMKII).

Murakoshi, Wang, and Yasuda (2011) examined the effects of Rho GTPase activation on the structural plasticity of single dendritic spines elucidating differences between the transient and sustained phases.

[10] Applying a low-frequency train of two-photon glutamate uncaging in a single dendritic spine can elicit rapid activation of both RhoA and Cdc42.

Half of the synapsing axons and dendritic spines are physically tethered by calcium-dependent cadherin, which forms cell-to-cell adherent junctions between two neurons.

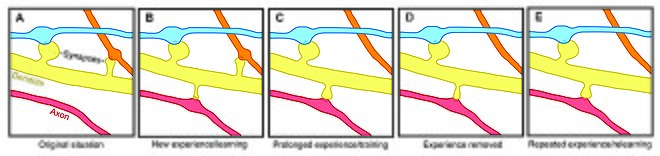

[1][22][23] This high rate of spine turnover may characterize critical periods of development and reflect learning capacity in adolescence—different cortical areas exhibit differing levels of synaptic turnover during development, possibly reflecting varying critical periods for specific brain regions.

On the one hand, experience and activity may drive the discrete formation of relevant synaptic connections that store meaningful information in order to allow for learning.

[1] In lab animals of all ages, environmental enrichment has been related to dendritic branching, spine density, and overall number of synapses.

Since the extent of spine remodeling correlates with success of learning, this suggests a crucial role of synaptic structural plasticity in memory formation.

One study using mice has noted a correlation between age-related reductions in spine densities in the hippocampus and age-dependent declines in hippocampal learning and memory.

[30] Emerging evidence has also shown dendritic spine abnormalities in the pain processing regions of the spinal cord nociceptive system, including superficial and intermediate zones of the dorsal horn.

Alterations in spine morphology may not only influence synaptic plasticity and information processing but also have a key role in many neurological diseases.

Furthermore, even subtle changes in dendritic spine densities or sizes can affect neuronal network properties,[34] which could lead to cognitive or mood alterations, impaired learning and memory, as well as pain hypersensitivity.

[29] Moreover, the findings suggest that maintaining spine health through therapies such as exercise, cognitive stimulation and lifestyle modifications may be helpful in preserving neuronal plasticity and improving neurological symptoms.

Despite experimental findings that suggest a role for dendritic spine dynamics in mediating learning and memory, the degree of structural plasticity's importance remains debatable.

For instance, studies estimate that only a small portion of spines formed during training actually contribute to lifelong learning.

Recent advances in imaging techniques along with increased use of two-photon glutamate uncaging have led to a wealth of new discoveries; we now suspect that there are voltage-dependent sodium,[36] potassium,[37] and calcium[38] channels in the spine heads.

[39] Cable theory provides the theoretical framework behind the most "simple" method for modelling the flow of electrical currents along passive neural fibres.

[41] It was designed to be analytically tractable and have as few free parameters as possible while retaining those of greatest significance, such as spine neck resistance.

The model drops the continuum approximation and instead uses a passive dendrite coupled to excitable spines at discrete points.

But since about a decade ago, new techniques of confocal microscopy demonstrated that dendritic spines are indeed motile and dynamic structures that undergo a constant turnover, even after birth.