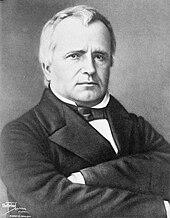

Denis-Benjamin Viger

A leader in the Patriote movement, he was a strong French-Canadian nationalist, but a social conservative in terms of the seigneurial system and the position of the Catholic church in Lower Canada.

Denis-Benjamin’s father, Denis Viger, began as a carpenter, branched out into small construction projects, and then developed a business selling potash to English markets.

Upon graduation, he trained in the law from 1794 to 1799, first under Louis-Charles Foucher, the solicitor-general for the province, then under Joseph Bédard, brother of the leader of the Parti canadien, and finally under Jean-Antoine Panet, the speaker of the Legislative Assembly.

[1][2] Even before he completed his legal studies, Viger began writing articles on political issues for the newspapers, with the first appearing in 1792 in the Montreal Gazette.

[1][2] Viger was a strong admirer of the British constitution, which he considered was an excellent balancing of the royal, aristocratic, and popular elements of the country.

Socially conservative, he was distrustful of the various constitutional developments in French, and did not consider American republicanism as an option, unlike his cousin Papineau.

In the Assembly and its committees, he defended the seigneurial system, the use of the customary law of Paris in Lower Canada, and the Catholic church.

Viger later acted as a go-between for his two cousins, Lartigue and Papineau, when tensions rose between the church and the Parti canadien in the lead-up to the Lower Canada Rebellion in 1837.

This time, the delegation to London to press their demands was composed of Neilson, Viger, and Austin Cuvillier, armed with petitions with more than 80,000 signatures.

[1][2] The increasing radicalisation of the Parti patriote was leading the British government to fear that Papineau and his supporters were seeking republicanism and ultimately independence.

Nor was he a member of the nascent para-military group, the Société des Fils de la Liberté, but he allowed them to train on his lands.

[1][2][17] There were also suspicions that the Banque du Peuple, in which his cousin Louis-Michel Viger was a major investor, was funnelling money to the Patriotes for the purchase of arms.

For example, in the summer of 1837, his cousin, Bishop Lartigue of Montreal, issued an episcopal letter, condemning the drift of the Parti patriote towards radicalism.

His house was searched once, in November 1837, but thereafter he was left alone for a year, even after the government declared martial law in the Montreal district on December 5, 1837.

However, when the Rebellion broke out a second time the next year, Viger was arrested on November 4, 1838, denounced by the Montreal Herald as the promoter of seditious newspapers.

Now in his mid-60s, a political veteran and nicknamed Le Vénérable, Viger was worried that the union proposal was designed to assimilate French-Canadians and undercut their culture.

[1][2][26][27] Throughout the term of the first Parliament, there were running disputes over the balance of powers between the elected Legislative Assembly and the appointed Governor General.

[1][28][29] Viger cooperated with Robert Baldwin, leader of the Reformers from Canada West, in introducing a series of resolutions affirming the role of the Legislative Assembly in reviewing the actions of the executive.

He appointed Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine from the French-Canadian Group, and Robert Baldwin from Canada West, to lead the Executive Council.

However, when Governor General Sir Charles Metcalfe succeeded Bagot in 1843, he asserted that while he would consult with the Executive Council, he could act independently, particularly in the appointments to government positions.

There was a major debate in the Legislative Assembly, which passed a motion supporting the former members of the Executive Council and criticising Metcalfe for his actions.

[1][31][32][33][34] Following the resignation of the LaFontaine–Baldwin ministry, Governor General Metcalfe was left with only one member in the Executive Council, the Provincial Secretary, Dominick Daly.

In December, Metcalfe persuaded Viger to accept office as joint premier, along with a moderate conservative Tory from Canada West, William Draper.

[1][2][35][36][37][38] Viger was heavily criticised by his former party companions for taking office under a Governor General who was hostile to responsible government and French-Canadians.

Political commentators at the time, and historians since, have found it difficult to understand Viger's decision to take office under Governor General Metcalfe, along with Draper, a Tory who had opposed the rebellions and strongly supported the ties with the United Kingdom.

He opposed LaFontaine's efforts to build a fully functioning alliance with Baldwin and the Reformers, because in his view that would delay the ultimate break-up.

Although the purpose of the bill was to compensate individuals in Canada East who had suffered property damage during the Rebellion, he argued that it was too costly for the provincial government.

[1][2][51] In articles written for the newspapers, Viger opposed the abolition of seigneurial tenure, a major land reform brought in by Lafontaine.

In 1858, fifty years after he was first elected to the Assembly of Lower Canada, he lost his seat in the Council for failure to attend two sessions of the Parliament.

His life, like those of the Bédards, the Panets, the Papineaus, was tied to the heroic battles where the existence of the Canadien nationality was several times in play and each time was saved by these noble supporters of liberty.The Montreal Gazette commented shortly after Viger's death that his life could be summed up by "a desire to secure the blessings of free government for his fellow countrymen.