Denshawai incident

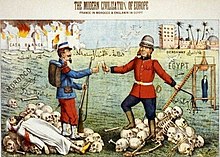

The Egyptian people had had a growing sense of nationalism long before the British occupation of Egypt in 1882 and the revolt of Ahmed Urabi.

He was in charge of economic reforms and worked to eliminate the debt caused by the Khedival regime primarily during the Ismail Pasha reign.

Newspaper writers maintained that, if not for the policies of the British government in Egypt, those positions could have been easily filled by capable, educated Egyptians.

[8] Additionally, Major-General Bullock, the Commanding Officer of the Army of Occupation, requested that the accused be tried under Khedival Decree rather than the reformed, Egyptian penal code.

[6] The day following the incident, the British Army arrested fifty-two men in the village (identified as members of the involved scuffle).

Five judges were assigned to adjudicate: Boutros Pasha Ghali (who was also the Minister of Justice), Ahmed Fathy Zaghlul, William Hayter, Lieutenant Colonel Ludlow, and Mr Bond.

Hassan Aly Mahfouz (owner of the pigeons), Youssef Hussein Selim, El Sayed Issa Salem, and Mohamed Darweesh Zahran, were convicted of pre-meditated murder of the officer who had died of heatstroke, with the claim that their actions had put him in that deadly position.

[9] Concerned with growing Egyptian nationalism, British officials thought it would be best to show their strength and make an example of the villager leaders involved.

As the war continued, the unrest sparked by the Denshawai incident was further aggravated by inflation, as well as food shortages in the country; severely damaging the Egyptian economy.

While the Allies were attempting to reach a post-war agreement, the Egyptian leaders, known as the Wafd, which later gave its name to the major political party, were denied entrance to France to meet with the Versailles peacemakers.

These riots, and the grievances that triggered them, provided Egyptian nationalists with both a focus for unified action, and a base of support that was wider than any they had attracted in the prewar decades.

Guy Aldred, who in 1907 compared the execution of Madan Lal Dhingra with the immunity given to the British officers in this incident, was sentenced to twelve months' hard labour for publishing The Indian Sociologist.

In a passage more noted for its picturesque description than for its literal accuracy, he stated: [T]hey had room for only one man on the gallows, and had to leave him hanging half an hour to make sure [he was dead] and give his family plenty of time to watch him swinging, thus having two hours to kill as well as four men, they kept the entertainment going by flogging eight men with fifty lashes each.He then went on in the same vein: If her [England’s] empire means ruling the world as Denshawai has been ruled in 1906 – and that, I am afraid, is what the Empire does mean to the main body of our aristocratic-military caste and to our Jingo plutocrats – then there can be no more sacred and urgent political duty on earth than the disruption, defeat, and suppression of the Empire, and, incidentally, the humanization of its supporters…Fifty years later, the Egyptian journalist Mohamed Hassanein Heikal said "the pigeons of Denshawai have come home to roost", to describe the aftermath of the Anglo-French strikes in Egypt in 1956.

"27 June 1906, 2:00 pm" is a related poem by Constantine P. Cavafy, that starts: "When the Christians took and hanged/ the innocent boy of seventeen/ his mother who there beside the scaffold/ had dragged herself..." The incident is mentioned in Ken Follett's 1980 spy novel The Key to Rebecca, set in Egypt.