Depictions of Muhammad

The ahadith (supplemental teachings) present an ambiguous picture,[3][4] but there are a few that have explicitly prohibited Muslims from creating visual depictions of human figures.

[9][10][11] With the notable exception of modern-day Iran,[12] depictions of Muhammad were never numerous in any community or era throughout Islamic history,[13][14] and appeared almost exclusively in the private medium of Persian and other miniature book illustration.

In the age of the Internet, a handful of caricature depictions printed in the European press have caused global protests and controversy and been associated with violence.

In Judaism, one of the Ten Commandments states "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image", while in the Christian New Testament all covetousness (greed) is defined as idolatry.

[24] Ibn Wahshiyya and Abu Nuʿaym al-Isfahani tell a second story in which a Meccan merchant visiting Syria is invited to a Christian monastery where several sculptures and paintings depict prophets and saints.

[30][31] The Ottoman hilye format customarily starts with the basmala shown on top and is separated in the middle by Quran 21:107: "And We have not sent you but as a mercy to the worlds".

[31][32] Four compartments set around the central one often contain the names of the Rashidun: Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali, each followed by radhi Allahu anhu "may God be pleased with him".

[13] Even so, there exists a "notable corpus of images of Muhammad produced, mostly in the form of manuscript illustrations, in various regions of the Islamic world from the thirteenth century through modern times".

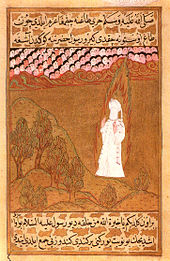

The illustrated book from the Persianate world (Warka and Gulshah, Topkapi Palace Library H. 841, attributed to Konya 1200–1250) contains the two earliest known Islamic depictions of Muhammad.

[34] According to Gruber, a good number of these paintings later underwent iconoclastic mutilations, in which the facial features of Muhammad were scratched or smeared, as Muslim views on the acceptability of veristic images changed.

[43] These images were also used in celebrations of the anniversary of the Mi'raj on 27 Rajab, when the accounts were recited aloud to male groups: "Didactic and engaging, oral stories of the ascension seem to have had the religious goal of inducing attitudes of praise among their audiences".

This "luminous" form of representation avoided the issues caused by "veristic" images, and could be taken to convey qualities of Muhammad's person described in texts.

For example, in 1963 an account by a Turkish author of a Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca was banned in Pakistan because it contained reproductions of miniatures showing Muhammad unveiled.

[12][52] Since the late 1990s, experts in Islamic iconography discovered images, printed on paper in Iran, portraying Muhammad as a teenager wearing a turban.

[53] The motif was taken from a photograph of a young Tunisian taken by the Germans Rudolf Franz Lehnert and Ernst Heinrich Landrock in 1905 or 1906, which had been printed in high editions on picture post cards till 1921.

While unseen, Muhammad is quoted, addressed directly and discussed throughout the film, and a distinct organ music cue signifies his off-camera presence.

[56] The earliest depiction of Muhammad in the West is found in a 12th-century manuscript of the Corpus Cluniacense, tied to Hermann of Carinthia's introduction to his translation of the Kitab al-Anwar of Abu al-Hasan Bakri.

It is perhaps inspired by Horace's Ars poetica, wherein the poet imagines "a woman, lovely above, foully ended in an ugly fish below" and asks if you would "restrain your laughter, my friends, if admitted to this private view?

Dante placed Muhammad in Hell, with his entrails hanging out (Canto 28): No barrel, not even one where the hoops and staves go every which way, was ever split open like one frayed Sinner I saw, ripped from chin to where we fart below.

Muhammad is represented in a 15th-century fresco Last Judgement by Giovanni da Modena and drawing on Dante, in the Church of San Petronio, Bologna, Italy[60] and artwork by Salvador Dalí, Auguste Rodin, William Blake, and Gustave Doré.

[69] In 2002, Italian police reported that they had disrupted a terrorist plot to destroy the Church of San Petronio in Bologna, which contains a 15th-century fresco depicting an image of Muhammad being dragged to hell by a demon (see above).

The wake of this scandal led to a crackdown on "insulting Muhammad" in general, and so police announced they were investigating Senang and would attempt to track down the author of the letter.

In the episode, "Cartoon Wars Part II", they intended to show Muhammad handing a salmon helmet to Peter Griffin, a character from the Fox animated series Family Guy.

The creators of South Park reacted by instead satirizing Comedy Central's double standard for broadcast acceptability by including a segment of "Cartoon Wars Part II" in which American president George W. Bush and Jesus defecate on the flag of the United States.

The controversy gained international attention after the Örebro-based regional newspaper Nerikes Allehanda published one of the drawings on August 18 to illustrate an editorial on self-censorship and freedom of religion.

[78] While several other leading Swedish newspapers had published the drawings already, this particular publication led to protests from Muslims in Sweden as well as official condemnations from several foreign governments including Iran,[79] Pakistan,[80] Afghanistan,[81] Egypt[82] and Jordan,[83] as well as by the inter-governmental Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC).

[85][86][87] The petition opposed a reproduction of a 17th-century Ottoman copy of a 14th-century Ilkhanate manuscript image (MS Arabe 1489) depicting Muhammad as he prohibited Nasīʾ.

The list included Stéphane Charbonnier, Lars Vilks, three Jyllands-Posten employees involved in the Muhammad cartoon controversy, Molly Norris from the Everybody Draw Mohammed Day and others whom AQAP accused of insulting Islam.

[95] On 16 October 2020, middle-school teacher Samuel Paty was killed and beheaded after showing Charlie Hebdo cartoons depicting Muhammad during a class discussion on freedom of speech.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in January 2010 confirmed to the New York Post that it had quietly removed all historic paintings which contained depictions of Muhammad from public exhibition.