Descartes' theorem

A version of the theorem using complex numbers allows the centers of the circles, and not just their radii, to be calculated.

In higher dimensions, an analogous quadratic equation applies to systems of pairwise tangent spheres or hyperspheres.

In ancient Greece of the third century BC, Apollonius of Perga devoted an entire book to the topic, Ἐπαφαί [Tangencies].

It has been lost, and is known largely through a description of its contents by Pappus of Alexandria and through fragmentary references to it in medieval Islamic mathematics.

[3] Instead, Descartes' theorem is formulated using algebraic relations between numbers describing geometric forms.

This is characteristic of analytic geometry, a field pioneered by René Descartes and Pierre de Fermat in the first half of the 17th century.

[4] Descartes discussed the tangent circle problem briefly in 1643, in two letters to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate.

[10][11] The special case of this theorem for one straight line and three circles was recorded on a Japanese sangaku tablet from 1824.

[12] Descartes' theorem was rediscovered in 1826 by Jakob Steiner,[13] in 1842 by Philip Beecroft,[14] and in 1936 by Frederick Soddy.

Soddy chose to format his version of the theorem as a poem, The Kiss Precise, and published it in Nature.

[17][18] The generalization is sometimes called the Soddy–Gosset theorem,[19] although both the hexlet and the three-dimensional version were known earlier, in sangaku and in the 1886 work of Robert Lachlan.

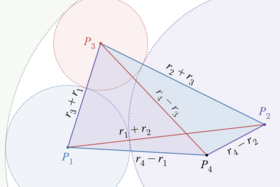

, Descartes' theorem says: If one of the four curvatures is considered to be a variable, and the rest to be constants, this is a quadratic equation.

[19][28][29] When three of the four circles are congruent, their centers form an equilateral triangle, as do their points of tangency.

Taking the square root of both sides leads to another alternative formulation of this case (with

This corresponds to the observation that, for all four curves to remain mutually tangent, the other two circles must be congruent.

Every four integers that satisfy the equation in Descartes' theorem form the curvatures of four tangent circles.

[34] Starting with any four mutually tangent circles, and repeatedly replacing one of the four with its alternative solution (Vieta jumping), in all possible ways, leads to a system of infinitely many tangent circles called an Apollonian gasket.

[33] The special cases of one straight line and integer curvatures combine in the Ford circles.

[35] The Ford circles belong to a special Apollonian gasket with root quadruple

[33] When the four radii of the circles in Descartes' theorem are assumed to be in a geometric progression with ratio

If the same progression is continued in both directions, each consecutive four numbers describe circles obeying Descartes' theorem.

Careful algebraic manipulation shows that this formula is equivalent to equation (1), Descartes' theorem.

[42] Descartes' theorem generalizes to mutually tangent great or small circles in spherical geometry if the curvature of the

the geodesic curvature of the circle relative to the sphere, which equals the cotangent of the oriented intrinsic radius

[46] Likewise, the theorem generalizes to mutually tangent circles in hyperbolic geometry if the curvature of the

This formula also holds for mutually tangent configurations in hyperbolic geometry including hypercycles and horocycles, if

[19][44] Although there is no 3-dimensional analogue of the complex numbers, the relationship between the positions of the centers can be re-expressed as a matrix equation, which also generalizes to

The result is a cyclic sequence of six spheres each tangent to its neighbors in the sequence and to the three fixed spheres, a configuration called Soddy's hexlet, after Soddy's discovery and publication of it in the form of another poem in 1936.

[15][16] Higher-dimensional configurations of mutually tangent hyperspheres in spherical or hyperbolic geometry, with curvatures defined as above, satisfy

[44][19] Kocik, Jerzy (2019), Proof of Descartes circle formula and its generalization clarified, arXiv:1910.09174