Dejima

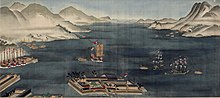

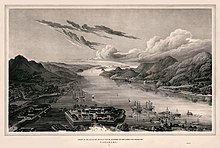

[1] For 220 years, it was the central conduit for foreign trade and cultural exchange with Japan during the isolationist Edo period (1600–1869), and the only Japanese territory open to Westerners.

The island was constructed by the Tokugawa shogunate, whose isolationist policies sought to preserve the existing sociopolitical order by forbidding outsiders from entering Japan while prohibiting most Japanese from leaving.

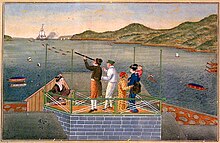

The open practice of Christianity was banned, and interactions between Dutch and Japanese traders were tightly regulated, with only a small number of foreign merchants being allowed to disembark in Dejima.

In 1570 daimyō Ōmura Sumitada converted to Catholicism (choosing Bartolomeu as his Christian name) and made a deal with the Portuguese to develop Nagasaki; soon the port was open for trade.

[citation needed] In 1580 Sumitada gave the jurisdiction of Nagasaki to the Jesuits, and the Portuguese obtained the de facto monopoly on the silk trade with China through Macau.

The shōgun Iemitsu ordered the construction of the artificial island in 1634, to accommodate the Portuguese traders living in Nagasaki and prevent the propagation of their religion.

However, in response to the uprising of the predominantly Christian population in the Shimabara-Amakusa region, the Tokugawa government decided to expel the Portuguese in 1639.

The departure of the Portuguese left the Dutch employees of the "Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie" ("VOC") as the sole Westerners with trade access to Japan.

[citation needed] The Dutch were watched by several Japanese officials, gatekeepers, night watchmen, and a supervisor (乙名, otona) with about fifty subordinates.

[citation needed] The chief VOC trading post officer in Japan was called the Opperhoofd by the Dutch, or Kapitan (from Portuguese capitão) by the Japanese.

Deer pelts and shark skin were transported to Japan from Formosa, as well as books, scientific instruments and many other rarities from Europe.

In return, the Dutch traders bought Japanese copper, silver, camphor, porcelain, lacquer ware, and rice.

[citation needed] To this was added the personal trade of VOC employees on Dejima, which was an important source of income for them and their Japanese counterparts.

Japanese civilians were likewise banned from entering Dejima, except interpreters, cooks, carpenters, clerks and yūjo ("women of pleasure") from the Maruyama teahouses.

Sometimes physicians such as Engelbert Kaempfer, Carl Peter Thunberg, and Philipp Franz von Siebold were called to high-ranking Japanese patients with the permission of the authorities.

[citation needed] The Opperhoofd was treated like the representative of a tributary state, which meant that he had to pay a visit of homage to the shōgun in Edo.

On arrival in Edo, the Opperhoofd and his retinue, usually his scribe and the factory physician, had to wait in the Nagasakiya (長崎屋), their mandatory residence, until they were summoned at the court.

[citation needed] Allegations published in the late 17th and early 18th century that Dutch traders were required by the Shogunate to renounce their Christian faith and undergo the test of treading on a fumi-e, an image of Jesus or Mary, are thought by modern scholars to be propaganda arising from the Anglo-Dutch Wars.

[11] Following the forced opening of Japan by US Navy Commodore Perry in 1854, the Bakufu suddenly increased its interactions with Dejima in an effort to build up knowledge of Western shipping methods.

[citation needed] The Dutch East India Company's trading post at Dejima was abolished when Japan concluded the Treaty of Kanagawa with the United States in 1858.

To better display Dejima's fan-shaped form, the project anticipated rebuilding only parts of the surrounding embankment wall that had once enclosed the island.

In the spring of 2006, the finishing touches were put on the Chief Factor's Residence, the Japanese Officials' Office, the Head Clerk's Quarters, the No.

[13] Long-term planning intends that Dejima will again be surrounded by water on all four sides; its characteristic fan-shaped form and all of its embankment walls will be fully restored.