Property (philosophy)

Understanding how different individual entities (or particulars) can in some sense have some of the same properties is the basis of the problem of universals.

A property is any member of a class of entities that are capable of being attributed to objects.

[2] Edward Jonathan Lowe even treated instantiation, characterization and exemplification as three separate kinds of predication.

At least since Plato, properties are viewed by numerous philosophers as universals, which are typically capable of being instantiated by different objects.

Philosophers opposing this view regard properties as particulars, namely tropes.

The other realist position asserts that properties are particulars (tropes), which are unique instantiations in individual objects that merely resemble one another to various degrees.

Transcendent realism, proposed by Plato and favored by Bertrand Russell, asserts that properties exist even if uninstantiated.

[1] Immanent realism, defended by Aristotle and David Malet Armstrong, contends that properties exist only if instantiated.

[1] The anti-realist position, often referred to as nominalism claims that properties are names we attach to particulars.

[7] Fragility, according to this view, identifies a real property of the glass (e.g. to shatter when dropped on a sufficiently hard surface).

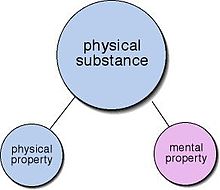

In other words, it is the view that non-physical, mental properties (such as beliefs, desires and emotions) inhere in some physical substances (namely brains).

In classical Aristotelian terminology, a property (Greek: idion, Latin: proprium) is one of the predicables.

For example, color is a determinable property because it can be restricted to redness, blueness, etc.

The reason for this is that impure properties are not relevant for similarity or discernibility but taking them into consideration nonetheless would result in the principle being trivially true.

[14] Another application of this distinction concerns the problem of duplication, for example, in the Twin Earth thought experiment.

[16] Daniel Dennett distinguishes between lovely properties (such as loveliness itself), which, although they require an observer to be recognised, exist latently in perceivable objects; and suspect properties which have no existence at all until attributed by an observer (such as being suspected of a crime).

[17] The ontological fact that something has a property is typically represented in language by applying a predicate to a subject.

[22][19] The distinction between properties and relations can hardly be given in terms that do not ultimately presuppose it.