Developmental biology

Differentiated cells usually produce large amounts of a few proteins that are required for their specific function and this gives them the characteristic appearance that enables them to be recognized under the light microscope.

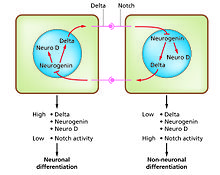

Control of their formation involves a process of lateral inhibition,[6] based on the properties of the Notch signaling pathway.

[7] For example, in the neural plate of the embryo this system operates to generate a population of neuronal precursor cells in which NeuroD is highly expressed.

If the latter, then each instance of regeneration is presumed to have arisen by natural selection in circumstances particular to the species, so no general rules would be expected.

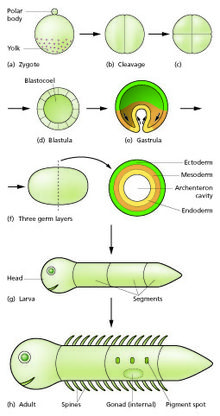

[15] This undergoes a period of divisions to form a ball or sheet of similar cells called a blastula or blastoderm.

Mouse epiblast primordial germ cells (see Figure: "The initial stages of human embryogenesis") undergo extensive epigenetic reprogramming.

[16] This process involves genome-wide DNA demethylation, chromatin reorganization and epigenetic imprint erasure leading to totipotency.

[17] Morphogenetic movements convert the cell mass into a three layered structure consisting of multicellular sheets called ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm.

In addition to the formation of the three germ layers themselves, these often generate extraembryonic structures, such as the mammalian placenta, needed for support and nutrition of the embryo,[18] and also establish differences of commitment along the anteroposterior axis (head, trunk and tail).

Because the inducing factor is produced in one place, diffuses away, and decays, it forms a concentration gradient, high near the source cells and low further away.

[20][21] The remaining cells of the embryo, which do not contain the determinant, are competent to respond to different concentrations by upregulating specific developmental control genes.

Among other functions, these transcription factors control expression of genes conferring specific adhesive and motility properties on the cells in which they are active.

Because of these different morphogenetic properties, the cells of each germ layer move to form sheets such that the ectoderm ends up on the outside, mesoderm in the middle, and endoderm on the inside.

[23][24] Morphogenetic movements not only change the shape and structure of the embryo, but by bringing cell sheets into new spatial relationships they also make possible new phases of signaling and response between them.

In addition, first morphogenetic movements of embryogenesis, such as gastrulation, epiboly and twisting, directly activate pathways involved in endomesoderm specification through mechanotransduction processes.

[25][26] This property was suggested to be evolutionary inherited from endomesoderm specification as mechanically stimulated by marine environmental hydrodynamic flow in first animal organisms (first metazoa).

But embryos fed by a placenta or extraembryonic yolk supply can grow very fast, and changes to relative growth rate between parts in these organisms help to produce the final overall anatomy.

Examples that have been especially well studied include tail loss and other changes in the tadpole of the frog Xenopus,[32][33] and the biology of the imaginal discs, which generate the adult body parts of the fly Drosophila melanogaster.

Once the embryo germinates from its seed or parent plant, it begins to produce additional organs (leaves, stems, and roots) through the process of organogenesis.

[38] Branching occurs when small clumps of cells left behind by the meristem, and which have not yet undergone cellular differentiation to form a specialized tissue, begin to grow as the tip of a new root or shoot.

This directional growth can occur via a plant's response to a particular stimulus, such as light (phototropism), gravity (gravitropism), water, (hydrotropism), and physical contact (thigmotropism).

In early development different vertebrate species all use essentially the same inductive signals and the same genes encoding regional identity.

[53] For studies of regeneration urodele amphibians such as the axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum are used,[54] and also planarian worms such as Schmidtea mediterranea.