Dieppe maps

[21] Common features of most of the Dieppe world maps (see Vallard 1547, Desceliers 1550) are the compass roses and navigational rhumb lines, suggestive of a sea-chart.

For example, the Desceliers 1550 map carries descriptions of early French attempts to colonise Canada, the conquests of Peru by the Spanish and the Portuguese sea-trade among the Spice Islands.

Most of the Dieppe maps depict a large land mass entitled Jave la Grande or terre de lucac (Locach) between what is now Indonesia and Antarctica.

[27] The Dieppe maps all depict the hypothetical southern continent, Terra Australis, incorporating a huge promontory extending northward called "Jave la Grande".

[28] Le Testu's Cosmographie Universelle, the sumptuous atlas he presented in 1556 to Gaspard II de Coligny, Grand Admiral of France, constituted a veritable encyclopaedia of the geographic and ethnographic knowledge of the time.

French historian Frank Lestringant has said: "The nautical fiction of Le Testu fulfilled the conditions of a technical instrumentality, while giving to King Henry II and his minister, Admiral Coligny, the… anticipatory image of an empire that awaited to be brought into being".

This imaginary land derived from the Antichthone of the Greeks and had already been reactivated, notably by the mathematician and cosmographer Oronce Fine (1531) and by Le Testu's predecessors of the Dieppe school.

According to the Portuguese historian Paolo Carile, the attitude of Le Testu reveals a cultural conflict between the old cosmographic beliefs and the demands of an empirical concept of geographical and ethnographical knowledge, influenced by the rigour of his Calvinist faith.

[32] Lucien Gallois noted in 1890, as Franz von Wieser had done before him, the undeniable "ressemblance parfaite" ("perfect resemblance") between Fine's 1531 mappemonde and Schöner's 1533 globe.

Following the 1519–1521 circumnavigation of the world by the expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan and completed after his death in the Philippines by Sebastian de Juan Sebastián Elcano, Schöner identified the Pacific Ocean with Ptolemy's Sinus Magnus, which he labelled on his 1523 globe, SINUS MAGNUS EOV[um] MARE DE SUR (the Great Gulf, Eastern Sea, South Sea").

The extent of French knowledge concerning Terra Australis in the mid-16th century is indicated by Lancelot Voisin de La Popelinière, who in 1582 published Les Trois Mondes, a work setting out the history of the discovery of the globe.

In Les Trois Mondes, La Popelinière pursued a geopolitical design by using cosmographic conjectures which were at the time quite credible, to theorize a colonial expansion by France into the Austral territories.

He was apparently ignorant that Francis Drake sailed through open sea to the south of Tierra del Fuego in 1578, proving it to be an island and not, as Magellan had supposed, part of Terra Australis.

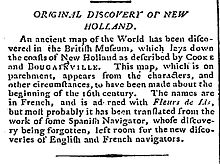

[42][43][44] The first writer to put these maps forward as evidence of Portuguese discovery of Australia was Alexander Dalrymple in 1786, in a short note to his Memoir Concerning the Chagos and Adjacent Islands.