Terra Australis

[11] Legends of Terra Australis Incognita—an "unknown land of the South"—date back to Roman times and before, and were commonplace in medieval geography, although not based on any documented knowledge of the continent.

[23] The Zeytung described the Portuguese voyagers passing through a strait between the southernmost point of America, or Brazil, and a land to the south west, referred to as vndtere Presill (or Brasilia inferior).

In an accompanying explanatory treatise, Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio ("A Most Lucid Description of All Lands"), he explained:The Portuguese, thus, sailed around this region, the Brasilie Regio, and discovered the passage very similar to that of our Europe (where we reside) and situated laterally between east and west.

From one side the land on the other is visible; and the cape of this region about 60 miles [97 km] away, much as if one were sailing eastward through the Straits of Gibraltar or Seville and Barbary or Morocco in Africa, as our Globe shows toward the Antarctic Pole.

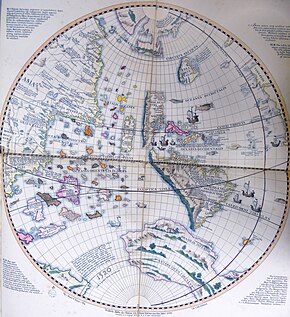

Terra Australis was depicted on the mid-16th-century Dieppe maps, where its coastline appeared just south of the islands of the East Indies; it was often elaborately charted, with a wealth of fictitious detail.

[32] Gerardus Mercator believed in the existence of a large Southern continent on the basis of cosmographic reasoning, set out in the abstract of his Atlas or Cosmographic Studies in Five Books, as related by his biographer, Walter Ghim, who said that even though Mercator was not ignorant that the Austral continent still lay hidden and unknown, he believed it could be "demonstrated and proved by solid reasons and arguments to yield in its geometric proportions, size and weight, and importance to neither of the other two, nor possibly to be lesser or smaller, otherwise the constitution of the world could not hold together at its centre".

[33] The Flemish geographer and cartographer, Cornelius Wytfliet, wrote concerning the Terra Australis in his 1597 book, Descriptionis Ptolemaicae Augmentum: The terra Australis is therefore the southernmost of all other lands, directly beneath the antarctic circle; extending beyond the tropic of Capricorn to the West, it ends almost at the equator itself, and separated by a narrow strait lies on the East opposite to New Guinea, only known so far by a few shores because after one voyage and another that route has been given up and unless sailors are forced and driven by stress of winds it is seldom visited.

[35] The Polus Antarcticus map of 1641 by Henricus Hondius, bears the inscription: "Insulas esse a Nova Guinea usque ad Fretum Magellanicum affirmat Hernandus Galego, qui ad eas explorandas missus fuit a Rege Hispaniae Anno 1576 (Hernando Gallego, who in the year 1576 was sent by the King of Spain to explore them, affirms that there are islands from New Guinea up to the Strait of Magellan)".

[37] Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, another Portuguese navigator sailing for the Spanish Crown, saw a large island south of New Guinea in 1606, which he named La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo.

In his 10th Memorial (1610), Queirós said: "New Guinea is the top end of the Austral Land of which I treat [discuss], and that people, and customs, with all the rest referred to, resemble them".

[39] Dutch father and son Isaac and Jacob Le Maire established the Australische Compagnie (Australian Company) in 1615 to trade with Terra Australis, which they called "Australia".

[40] The Dutch expedition to Valdivia of 1643 intended to round Cape Horn sailing through Le Maire Strait but strong winds made it instead drift south and east.

[41] The small fleet led by Hendrik Brouwer managed to enter the Pacific ocean sailing south of the island disproving earlier beliefs that it was part of Terra Australis.

At its largest, the continent included Tierra del Fuego, separated from South America by a small strait; New Guinea; and what would come to be called Australia.

As long as it appeared on maps at all, the continent minimally included the unexplored lands around the South Pole, but generally much larger than the real Antarctica, spreading far north – especially in the Pacific Ocean.

Alexander Dalrymple, the Examiner of Sea Journals for the English East India Company,[45] whilst translating some Spanish documents captured in the Philippines in 1762, found de Torres's testimony.

There is at present no trade from Europe thither, though the scraps from this table would be sufficient to maintain the power, dominion, and sovereignty of Britain, by employing all its manufacturers and ships.

Whoever considers the Peruvian empire, where arts and industry flourished under one of the wisest systems of government, which was founded by a stranger, must have very sanguine expectations of the southern continent, from whence it is more than probable Mango Capac, the first Inca, was derived, and must be convinced that the country, from whence Mango Capac introduced the comforts of civilized life, cannot fail of amply rewarding the fortunate people who shall bestow letters instead of quippos (quipus), and iron in place of more awkward substitutes.

[49] The aims of the expedition were revealed in days following: "To-morrow morning Mr. Banks, Dr. Solano [sic], with Mr. Green, the Astronomer, will set out for Deal, to embark on board the Endeavour, Capt.

He wrote in his Journal on 31 March 1770 that the Endeavour's voyage "must be allowed to have set aside the most, if not all, the Arguments and proofs that have been advanced by different Authors to prove that there must be a Southern Continent; I mean to the Northward of 40 degrees South, for what may lie to the Southward of that Latitude I know not".

[52] The second voyage of James Cook aboard HMS Resolution explored the South Pacific for the landmass between 1772 and 1775 whilst also testing Larcum Kendall's K1 chronometer as a method for measuring longitude.

He wrote: There is no probability, that any other detached body of land, of nearly equal extent, will ever be found in a more southern latitude; the name Terra Australis will, therefore, remain descriptive of the geographical importance of this country, and of its situation on the globe: it has antiquity to recommend it; and, having no reference to either of the two claiming nations,[Note 1] appears to be less objectionable than any other which could have been selected.

...with the accompanying note at the bottom of the page: Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term, it would have been to convert it into AUSTRALIA; as being more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth.

A land feature known as the "Province of Beach" or "Boeach" – from the Latin Provincia boëach – appears to have resulted from mistranscriptions of a name in Marco Polo's Il Milione (Book III).

In August 1642, the Council of the Dutch East India Company – evidently still relying on Linschoten's map – despatched Abel Tasman and Frans Jacobszoon Visscher on a voyage of exploration, of which one of the objects was to obtain knowledge of "all the totally unknown provinces of Beach".