Differential heat treatment

Differential heat treatment is a method used to alter the properties of various parts of a steel object differently, producing areas that are harder or softer than others.

[1] Differential hardening is a method used in heat treating swords and knives to increase the hardness of the edge without making the whole blade brittle.

This method is sometimes called differential tempering, but this term more accurately refers to a different technique, which originated with the broadswords of Europe.

This helps to create a tough blade that will maintain a very sharp, wear-resistant edge, even during rough use such as found in combat.

[5][6] The insulation layer is quite often a mixture of clays, ashes, polishing stone powder, and salts, which protects the back of the blade from cooling very quickly when quenched.

[5] The exact composition of the clay mixture, the thickness of the coating, and even the temperature of the water were often closely guarded secrets of the various bladesmithing schools.

Both to help prevent cracking and to produce uniformity in the hardness of each area, the smith will need to ensure that the temperature is even, lacking any hot spots from sitting next to the coals.

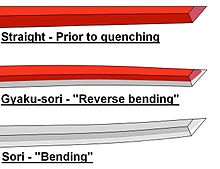

The diffusionless transformation causes the edge to "freeze" suddenly in a thermally expanded state, but allows the back to contract as it cools slower.

[6] Care must be taken to plunge the sword quickly and vertically (edge first), for if one side enters the quenching fluid before the other the cooling may be asymmetric and cause the blade to bend sideways (warp).

After quenching and tempering, the blade was traditionally given a rough shape with a metal-cutting draw knife (sen) before sending to a polisher for sharpening,[11] although in modern times an electric belt sander is often used instead.

The pearlite takes on longer, deeper scratches, and either appears shiny and bright, or sometimes dark depending on the viewing angle.

[12] When polished or etched with acid to reveal these features, a distinct boundary is observed between the martensite portion of the blade and the pearlite.

Between the hardened edge and the hamon lies an intermediate zone, called the '"nioi" in Japanese, which is usually only visible at long angles.

During this time, great attention began to be paid in Japan to making decorative hamons, by carefully shaping the clay.

It became very common during this era to find swords with wavy hamons, flowers or clovers depicted in the temper line, rat's feet, trees, or other shapes.

By the eighteenth century, decorative hamons were often being combined with decorative folding techniques to produce entire landscapes, complete with specific islands, crashing waves, hills, mountains, rivers, and sometimes low spots were cut in the clay to produce niye far away from the hamon, creating effects such as birds in the sky.

However, if properly protected and maintained, these blades can usually hold an edge for long periods of time, even after slicing through bone and flesh, or heavily matted bamboo to simulate cutting through body parts, as is in iaido.

Unlike the nioi, the boundary between the hot and cold metal formed by this heat-affected zone causes extremely rapid cooling when quenched.

This makes the surface very resistant to wear, but provides tougher metal directly underneath it, leaving the majority of the object unchanged.

Differential tempering begins by taking steel that has been uniformly quenched and hardened, and then heating it in localized areas to reduce the hardness.

Differential tempering was often used to provide a very hard cutting edge, but to soften parts of the tool that are subject to impact and shock loading.

The hardness of the cutting edge is generally controlled by the chosen color, but will also be affected primarily by the carbon content in the steel, plus a variety of other factors.

The exact hardness of the soft end depends on many factors, but the main one is the speed at which the steel was heated, or how far the colors spread out.

[22][23] Heating in just one area, like the flat end of a center punch, will cause the grade to spread evenly down the length of the tool.

Eventually, this process was applied to swords and knives, to produce mechanical effects that were similar to differential hardening, but with some important differences.

In this way, although it is less time-consuming than differential hardening with clay, once the process starts the smith must be vigilant, carefully guiding the heat.

[26] When a sword, knife or tool is evenly quenched, the entire object turns into martensite, which is extremely hard, without the formation of soft pearlite.

When tempering high-carbon steel in the blacksmith method, the color provides a general indication of the final hardness, although some trial-and-error is usually required to match the right color to the type of steel to achieve the exact hardness, because the carbon content, the heating speed, and even the type of heat source will affect the outcome.

The sword will often be tempered to slightly higher temperatures to increase the impact resistance at a cost in the ability to hold a sharp edge when cutting.

This may leave very little difference between the edge and the center, and the benefits of this method, over tempering the sword evenly at a point somewhere in the middle, may not be very substantial.