Differential topology

In this sense differential topology is distinct from the closely related field of differential geometry, which concerns the geometric properties of smooth manifolds, including notions of size, distance, and rigid shape.

By comparison differential topology is concerned with coarser properties, such as the number of holes in a manifold, its homotopy type, or the structure of its diffeomorphism group.

[1] The central goal of the field of differential topology is the classification of all smooth manifolds up to diffeomorphism.

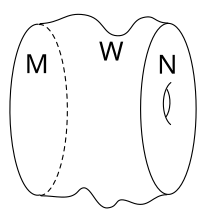

Important tools in studying the differential topology of smooth manifolds include the construction of smooth topological invariants of such manifolds, such as de Rham cohomology or the intersection form, as well as smoothable topological constructions, such as smooth surgery theory or the construction of cobordisms.

[7] Oftentimes more geometric or analytical techniques may be used, by equipping a smooth manifold with a Riemannian metric or by studying a differential equation on it.

Care must be taken to ensure that the resulting information is insensitive to this choice of extra structure, and so genuinely reflects only the topological properties of the underlying smooth manifold.

For example, the Hodge theorem provides a geometric and analytical interpretation of the de Rham cohomology, and gauge theory was used by Simon Donaldson to prove facts about the intersection form of simply connected 4-manifolds.

For instance, volume and Riemannian curvature are invariants that can distinguish different geometric structures on the same smooth manifold—that is, one can smoothly "flatten out" certain manifolds, but it might require distorting the space and affecting the curvature or volume.

[9] Some constructions of smooth manifold theory, such as the existence of tangent bundles,[10] can be done in the topological setting with much more work, and others cannot.

One of the main topics in differential topology is the study of special kinds of smooth mappings between manifolds, namely immersions and submersions, and the intersections of submanifolds via transversality.

They both study primarily the properties of differentiable manifolds, sometimes with a variety of structures imposed on them.

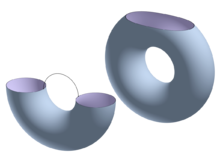

From the point of view of differential topology, the donut and the coffee cup are the same (in a sense).

This is an inherently global view, though, because there is no way for the differential topologist to tell whether the two objects are the same (in this sense) by looking at just a tiny (local) piece of either of them.