Digamma function

,[4] and it asymptotically behaves as[5] for complex numbers with large modulus (

or Ϝ[6] (the uppercase form of the archaic Greek consonant digamma meaning double-gamma).

For half-integer arguments the digamma function takes the values If the real part of z is positive then the digamma function has the following integral representation due to Gauss:[7] Combining this expression with an integral identity for the Euler–Mascheroni constant

, so the previous formula may also be written A consequence is the following generalization of the recurrence relation: An integral representation due to Dirichlet is:[7] Gauss's integral representation can be manipulated to give the start of the asymptotic expansion of

[8] This formula is also a consequence of Binet's first integral for the gamma function.

Binet's second integral for the gamma function gives a different formula for

Euler's product formula for the gamma function, combined with the functional equation and an identity for the Euler–Mascheroni constant, yields the following expression for the digamma function, valid in the complex plane outside the negative integers (Abramowitz and Stegun 6.3.16):[1] Equivalently, The above identity can be used to evaluate sums of the form where p(n) and q(n) are polynomials of n. Performing partial fraction on un in the complex field, in the case when all roots of q(n) are simple roots, For the series to converge, otherwise the series will be greater than the harmonic series and thus diverge.

[15][13] Similar series with the Cauchy numbers of the second kind Cn reads[15][13] A series with the Bernoulli polynomials of the second kind has the following form[13] where ψn(a) are the Bernoulli polynomials of the second kind defined by the generating equation It may be generalized to where the polynomials Nn,r(a) are given by the following generating equation so that Nn,1(a) = ψn(a).

[13] Similar expressions with the logarithm of the gamma function involve these formulas[13] and where

This satisfies the recurrence relation of a partial sum of the harmonic series, thus implying the formula where γ is the Euler–Mascheroni constant.

Actually, ψ is the only solution of the functional equation that is monotonic on R+ and satisfies F(1) = −γ.

This fact follows immediately from the uniqueness of the Γ function given its recurrence equation and convexity restriction.

This implies the useful difference equation: There are numerous finite summation formulas for the digamma function.

[16][17] More complicated formulas, such as are due to works of certain modern authors (see e.g.

We also have [19] For positive integers r and m (r < m), the digamma function may be expressed in terms of Euler's constant and a finite number of elementary functions[20] which holds, because of its recurrence equation, for all rational arguments.

The expansion can be found by applying the Euler–Maclaurin formula to the sum[22] The expansion can also be derived from the integral representation coming from Binet's second integral formula for the gamma function.

[25] The mean value theorem implies the following analog of Gautschi's inequality: If x > c, where c ≈ 1.461 is the unique positive real root of the digamma function, and if s > 0, then Moreover, equality holds if and only if s = 1.

[26] Inspired by the harmonic mean value inequality for the classical gamma function, Horzt Alzer and Graham Jameson proved, among other things, a harmonic mean-value inequality for the digamma function:

[27] The asymptotic expansion gives an easy way to compute ψ(x) when the real part of x is large.

Beal[28] suggests using the above recurrence to shift x to a value greater than 6 and then applying the above expansion with terms above x14 cut off, which yields "more than enough precision" (at least 12 digits except near the zeroes).

The series matches the overall behaviour well, that is, it behaves asymptotically as it should for large arguments, and has a zero of unbounded multiplicity at the origin too.

A similar series exists for exp(ψ(x)) which starts with

If one calculates the asymptotic series for ψ(x+1/2) it turns out that there are no odd powers of x (there is no x−1 term).

This leads to the following asymptotic expansion, which saves computing terms of even order.

Another alternative is to use the recurrence relation or the multiplication formula to shift the argument of

is real-valued, it can easily be deduced that Apart from Gauss's digamma theorem, no such closed formula is known for the real part in general.

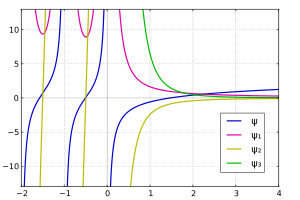

The only one on the positive real axis is the unique minimum of the real-valued gamma function on R+ at x0 = 1.46163214496836234126.... All others occur single between the poles on the negative axis: Already in 1881, Charles Hermite observed[32] that holds asymptotically.

A better approximation of the location of the roots is given by and using a further term it becomes still better which both spring off the reflection formula via and substituting ψ(xn) by its not convergent asymptotic expansion.

The correct second term of this expansion is 1/2n, where the given one works well to approximate roots with small n. Another improvement of Hermite's formula can be given:[11] Regarding the zeros, the following infinite sum identities were recently proved by István Mező and Michael Hoffman[11][33] In general, the function can be determined and it is studied in detail by the cited authors.

The digamma function appears in the regularization of divergent integrals this integral can be approximated by a divergent general Harmonic series, but the following value can be attached to the series

visualized using domain coloring