Geometric series

While Greek philosopher Zeno's paradoxes about time and motion (5th century BCE) have been interpreted as involving geometric series, such series were formally studied and applied a century or two later by Greek mathematicians, for example used by Archimedes to calculate the area inside a parabola (3rd century BCE).

Today, geometric series are used in mathematical finance, calculating areas of fractals, and various computer science topics.

, and the next one being the initial term multiplied by a constant number known as the common ratio

By multiplying each term with a common ratio continuously, the geometric series can be defined mathematically as:[1]

[3] When summing infinitely many terms, the geometric series can either be convergent or divergent.

Decimal numbers that have repeated patterns that continue forever can be interpreted as geometric series and thereby converted to expressions of the ratio of two integers.

alone: The rate of convergence shows how the sequence quickly approaches its limit.

[6] The pattern of convergence also depends on the sign or complex argument of the common ratio.

, adjacent terms in the geometric series alternate between positive and negative, and the partial sums

approaches 1, polynomial division or L'Hospital's rule recovers the case

approaches infinity, the absolute value of r must be less than one for this sequence of partial sums to converge to a limit.

[12] This special class of power series plays an important role in mathematics, for instance for the study of ordinary generating functions in combinatorics and the summation of divergent series in analysis.

However, both the ratio test and the Cauchy–Hadamard theorem are proven using the geometric series formula as a logically prior result, so such reasoning would be subtly circular.

[16] 2,500 years ago, Greek mathematicians believed that an infinitely long list of positive numbers must sum to infinity.

Zeno's paradox revealed to the Greeks that their assumption about an infinitely long list of positive numbers needing to add up to infinity was incorrect.

[17] Euclid's Elements has the distinction of being the world's oldest continuously used mathematical textbook, and it includes a demonstration of the sum of finite geometric series in Book IX, Proposition 35, illustrated in an adjacent figure.

His method was to dissect the area into infinite triangles as shown in the adjacent figure.

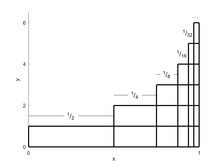

and its sum is:[19] In addition to his elegantly simple proof of the divergence of the harmonic series, Nicole Oresme[20] proved that the arithmetico-geometric series known as Gabriel's Staircase,[21]

The first dimension is horizontal, in the bottom row, representing the geometric series with initial value

More specifically in mathematical finance, geometric series can also be applied in time value of money; that is to represent the present values of perpetual annuities, sums of money to be paid each year indefinitely into the future.

It can also be used to estimate the present value of expected stock dividends, or the terminal value of a financial asset assuming a stable growth rate.

However, the assumption that interest rates are constant is generally incorrect and payments are unlikely to continue forever since the issuer of the perpetual annuity may lose its ability or end its commitment to make continued payments, so estimates like these are only heuristic guidelines for decision making rather than scientific predictions of actual current values.

[3] In addition to finding the area enclosed by a parabola and a line in Archimedes' The Quadrature of the Parabola,[19] the geometric series may also be applied in finding the Koch snowflake's area described as the union of infinitely many equilateral triangles (see figure).

Various topics in computer science may include the application of geometric series in the following:[citation needed] While geometric series with real and complex number parameters

are most common, geometric series of more general terms such as functions, matrices, and

[23] The mathematical operations used to express a geometric series given its parameters are simply addition and repeated multiplication, and so it is natural, in the context of modern algebra, to define geometric series with parameters from any ring or field.

[24] Further generalization to geometric series with parameters from semirings is more unusual, but also has applications; for instance, in the study of fixed-point iteration of transformation functions, as in transformations of automata via rational series.

, and while this is counterintuitive from the perspective of real number absolute value (where

[23] When the multiplication of the parameters is not commutative, as it often is not for matrices or general physical operators, particularly in quantum mechanics, then the standard way of writing the geometric series,

These choices may correspond to important alternatives with different strengths and weaknesses in applications, as in the case of ordering the mutual interferences of drift and diffusion differently at infinitesimal temporal scales in Ito integration and Stratonovitch integration in stochastic calculus.