Digestive system of gastropods

Gastropods (snails and slugs) as the largest taxonomic class of the mollusca are very diverse: the group includes carnivores, herbivores, scavengers, filter feeders, and even parasites.

Another distinctive feature of the digestive tract is that, along with the rest of the visceral mass, it has undergone torsion, twisting around through 180 degrees during the larval stage, so that the anus of the animal is located above its head.

[1] A number of species have developed special adaptations to feeding, such as the "drill" of some limpets, or the harpoon of the neogastropod genus Conus.

The highly modified parasitic genus Enteroxenos has no digestive tract at all, and simply absorbs the blood of its host through the body wall.

Several herbivorous species, as well as carnivores that prey on sessile animals, have also developed simple jaws, which help to hold the food steady while the radula works on it.

Salivary glands plays primary role in the anatomical and physiological adaptations of the digestive system of predatory gastropods.

[3] Ducts from large salivary glands lead into the buccal cavity, and the oesophagus also supplies the digestive enzymes that help to break down the food.

Usually, the food is embedded in a string of mucus produced in the mouth, creating a coiled conical mass in the style sac.

The anterior portion of the stomach opens into a coiled intestine, which helps to resorb water from the food, producing faecal pellets.

mo - mouth

r - radula

ph - pharynx

sgl and sgr - salivary glands

oe - oesophagus

i - intestine

a - anus

dg - digestive gland .

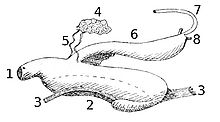

1-2 - buccal mass,

1 - mouth,

2 - pharynx,

3 - retractor muscles of the pharynx,

4 - salivary glands,

5 - salivary ducts,

6 - oesophagus,

7 - stomach.

1-2 - buccal mass,

1 - mouth,

2 - pharynx,

3 - retractor muscles of the pharynx,

4 - salivary glands,

5 - salivary ducts,

6 - oesophagus and stomach,

7 - intestine,

8 - hepatic ducts.