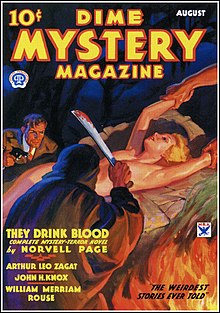

Dime Mystery Magazine

The new genre became known as "weird menace" fiction; the publisher, Harry Steeger, was inspired to create the new policy by the gory dramatizations he had seen at the Grand Guignol theater in Paris.

Most of the stories in Dime Mystery were considered low-quality pulp fiction by critics, but some well-known authors also appeared in the magazine, including Edgar Wallace, Ray Bradbury, Norvell Page, and Wyatt Blassingame.

In 1929, Harry Steeger was employed at Dell Publishing as a magazine editor, and Harold Goldsmith was at Ace Publications, working as a business manager.

[2] The new magazine's sales were weak,[1] but rather than cancel Dime Mystery, Steeger decided to change it to focus more on a particular kind of horror story: ones which appeared to be about supernatural events but had rational explanations.

[1] The title was initially Dime Mystery Book Magazine,[9] and the selling point, as the cover declared, was "A New $2.00 Detective Novel".

[1] Both were published by Fiction House and, although both cost twice as much as Dime Mystery, at 20 cents, they were well-established, reprinting long stories by well-known writers such as Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, and Ellery Queen.

[4] Rather than giving up on the magazine, which would have meant losing its second-class mailing permit,[note 1] Steeger decided to change its focus to horror.

Steeger was inspired by performances he had seen at the Grand Guignol Theater in Paris, which provided gory dramatizations of murder and torture.

[15] Terrill also gave his authors a working definition of the terms he was using: "Horror is what a girl would feel if, from a safe distance, she watched the ghoul practice diabolical rites upon a victim.

The explanation is that the villain in the story is killing key businessmen to depress stock prices, and to distract attention from his financial operations he gives the bodies to piranhas.

[2] Page later published an article in Writer's Yearbook explaining how he wrote the story and chose the plot elements: "the maximum of terror would be obtained by converting living men into nice white skeletons within a few minutes and concealing the means by which this was done... To have the horror of the story to the full, these skeletons must be flaunted in the face of the city, they must appear at the festive board, thud at the feet of the police commissioner entering headquarters.

Pulp historian Robert Jones quotes a typical description of a monster: "Grey-green was the face, with hollow cheeks and lank, lean jaws.

[17] Jones lists "The Corpse-Maker", from the November 1933 issue, as one of Cave's best stories: "A criminal who was horribly disfigured when making his escape from prison ... directs the murder of the jurors who convicted him.

The hero visits a deserted house and finds a girl there, and the two are attacked by a dangerous escapee from an asylum, who batters down doors to get at them, and climbs down the chimney when foiled.

[19] Blassingame also argued that each story could not be completely impossible: "A single definite fact can be stretched to amazing proportions and will be accepted, but you must make your explanation sound and convincing.

"[20] This advice was not always followed: Weinberg comments that although the stories always tried to explain away any apparently supernatural events, "the explanations often left major holes in the plot glaringly revealed...

[17][22] Paul Ernst also sold a few fantasies to Dime Mystery, including "The Devil's Doorstep" in the October 1935 issue, about a couple who buy a house with a doorway into hell.

[22] Some non-fiction material appeared as well, including "History's Gallery of Monsters", a series of ten articles by John Kobler.

The wife must agree to endure the pain for two hours to win their freedom: needles are inserted in her breast and "other tender parts of her body", and she is stretched on a rack and woken by drugs when she faints.

[17][25] One detective protagonist had hemophilia and had to avoid even the slightest scratch; another was an insomniac when working on a mystery; another was deaf and had to lip-read; another was an amnesiac.

After the July 1941 issue, Dime Mystery printed ordinary detective fiction along with some fantasy, including some early stories by Ray Bradbury.

Pulp historian Robert Kenneth Jones lists Rogers Terrill as the first editor, with the editorship passing to Chandler Whipple in about 1941, and to Loring Dowst in about 1943.

[29] An article in Writer's Digest in December 1942 about publishing staff who had left to serve in the military listed John Bender as the editor of Dime Mystery.