Dingo–dog hybrid

The full extent of the effects of this process is currently unknown and the possibility of potential problems, as well as the wish to preserve the "pure" dingo, often leads to a strong rejection of the interbreeding.

Since then, some of those dogs dispersed into the wild (both deliberately and accidentally) and founded feral populations, especially in places where the dingo numbers had been severely reduced due to human intervention.

Occasionally claims are made that interbreeding of dingoes and domestic dogs together with successful rearing of hybrids is a rare phenomenon in the wild due to supposedly radical differences in behaviour and biology and the harshness of the wilderness.

However, cases of dogs that came from human households but nonetheless manage to survive on their own (even by active hunting) and to successfully rear pups have been consistently proven.

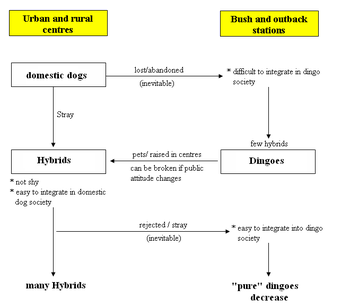

However, since interactions between dingoes and feral domestic dogs in the bush differ greatly from those in urban places, so too do the rates of hybridisation.

[2] The most likely possibility is that the territorial behaviour of established dingo-packs, which keeps away all foreign dogs (dingoes included) and prevents them from breeding, curbs the rate of interbreeding.

[11] Dingo-samples that have been collected in the 1960s and 1970s indicated that half of the wild dogs of southern Tasmania were dingo-hybrids; analyses from the early 1980s supported the trend of increasing interbreeding.

[17] At the turn of the millennium only 74% of 180 skulls from seven main areas of Australia could be classified as dingo-skulls during measurements and none of the populations consisted exclusively of dingoes.

Traditional methods for the identification for dingoes, dingo-hybrids and other domestic dogs (based on skull features, breeding patterns and fur colour) also indicate that interbreeding is widespread and occurs in all populations of Australia, especially in the East and the South of the continent.

[13] Even in areas that were once regarded as safe for "pure" dingoes, like the Kakadu national park or parts of the Northern Territory, dingo-hybrids now appear on the border zones of bush and settlements.

[21] Genetic analyses during the last years came to the conclusion that the populations of wild dogs in the southern Blue Mountains consists of 96.8% dingo-hybrids.

[28] Also reports by early settlers in the Blue Mountains region of NSW described dingoes which had wide variations in coat colours.

[31] Unlike dingoes other feral domestic dogs and dingo-hybrids are theoretically capable to come in heat twice annually and tend to have a breeding cycle less influenced by the seasons.

[33] Additionally, the average age of wild living domestic dogs in Australia is also not higher than what is considered normal for dingoes.

some scientists from the University of New South Wales developed a relatively reliable method with 20 genetic "fingerprints" using DNA from skin and blood samples to determine the "purity" of a dingo.

[37] Although genetic testing can theoretically determine whether an individual is a hybrid, "pure" dingo or another domestic dog, mistakes in results cannot be excluded.

During this a hitherto unknown form of the "pure" dingo was discovered (based on DNA and skull features): a white dog with orange spots on the fur.

[25] Contrary to constantly recurring claims of radical differences in behaviour[38][39] and biology,[40] a single annual breeding cycle,[41][42] seasonal adapted oestrus,[43] monogamy,[42][44] parental care by the males,[42][43] regulation of breeding via ecological[43] and social factors,[44] and howling[45] have all been observed among domestic dogs of most diverse backgrounds.

It was feared that the German Shepherds (partly due to the old name "Alsatian Wolfdog") would be a danger to sheep, become friendly with dingoes and possibly interbreed with them.

[11] Protection for these dogs should be based on how and where they live, as well as on their cultural and ecological importance, instead of concentrating on precise definitions or concerns about genetic "purity".

[49] Essentially the genetic integrity of the dingo is already lost due to interbreeding; however, the importance of this phenomenon is disputable according to Corbett and Daniels, since the genes come from a domesticated version of the same species.

Here, for instance, the molecular biologist Alan Wilton from the University of New South Wales argues that a maximizing of the "genetic purity" is an essential aspect of the dingo conservation.

[18] Dingo-hybrids would supposedly increase the predation on native species, because they would have more litters per year and therefore would have to raise more pups and some of them would be bigger than the average dingo.

Furthermore, hybrids and other feral domestic dogs would probably not have the same tourist effect, because they don't correspond with the current expectations on wild dingoes.

It is proven that there is a much wider range of fur colours, skull features and body sizes among the modern day wild dog population than in the times before the European colonization.

[20] According to David Jenkins, the claims stating that hybrids are bigger, more aggressive and a risk to public safety have so far not been supported by data and personal experience.

He mentioned that there are reports of one or two unusually big dogs captured each year, but that most hybrids are close to what's considered to be the normal weight range of dingoes.

In addition, Jenkins has encountered wild dingoes and hybrids and reported that "there's something really going on in that hard-wired brain", but also that the dogs "tend to be curious, rather than aggressive".

[2] One example in this topic are the bush rats, where it is also seen as unlikely that there could be problems due to the dingo-hybrids, because these rodents had been exposed to the influence of the dingoes for thousands of years.

The same ecological role was officially reported for the hybrids of the Namadgi-national park who filled the place of the apex predator and kept kangaroo numbers low.