Dioscorus of Aphrodito

[7] The collection of Greek and Coptic papyri associated with Dioscorus and Aphrodito is one of the most important finds in the history of papyrology and has shed considerable light on the law and society of Byzantine Egypt.

[8] The papyri are also considered significant because of their mention of Coptic workers and artists dispatched to the Levant and Arabia to work on early Umayyad architectural projects.

[12] Most importantly, the excavator Gustave Lefebvre unearthed an archive of sixth-century legal, business, and personal papers, and original poetry.

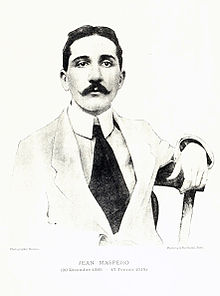

These were turned over to the young scholar Jean Maspero, son of the Director of the Antiquities Service of Egypt, who edited and published the documents and poems in several journal articles [13] and two volumes of the Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire: Papyrus grecs d’époque byzantine (Cairo 1911, 1913).

Jean was killed in the battle at Vauquois on the Lorraine during World War I, and his father Gaston completed the third volume of Dioscorian papyri in 1916.

Other Dioscorian papyri, obtained by antiquities dealers through sales and clandestine excavations,[14] were published in Florence, London, Paris, Strasbourg, Princeton, Ann Arbor, the Vatican, etc.

Before the 6th century, however, Aphroditopolis lost its status as a city, and the capital of the Aphroditopolite Nome was moved across the Nile River to Antaeopolis.

[16] The village of Aphrodito and the city of Antaeopolis were part of the larger administrative region of the Thebaid, which was under the jurisdiction of a doux, appointed by the Byzantine Emperor.

[22] In Northern Egypt, the areas of Nitria, Kellia, and Wadi Natrun contained large monastic centers that attracted devout followers from both the Eastern and Western halves of the Byzantine Empire.

[26] In fact, Aphrodito and its vicinity “boasted over thirty churches and nearly forty monasteries.”[27] There is no surviving record for the early years of Dioscorus.

[32] Back in Aphrodito, Dioscorus married, had children, and pursued a career similar to his father's: acquiring, leasing out, and managing property, and helping in the administration of the village.

But surmising from the surviving documents, one can conclude that he was attracted by the opportunity to advance his legal career in the proximity of the Duke and likewise was compelled by the increasing violence of the pagarch against Aphrodito and his own family.

[42] The legal documents from that period show that Dioscorus wrote the final will for the Surgeon General (Phoebammon),[43] arbitrated in family property disputes,[44] composed marriage and divorce contracts,[45] and continued writing petitions about the offenses of the pagarch.

Menas and his men then attacked the village of Aphrodito itself: he blocked the irrigation, extorted money, burned down homes, and violated the nuns.

The violent crimes against Aphrodito and Dioscorus (described above) were committed under the reign of Justin II, who had launched a savage persecution of Christians that did not adhere to Chalcedonian dogmas, including Egyptian Copts.

Then between 1911 and 1916, Jean and Gaston Maspero republished the poems along with Dioscorian documents in three volumes of Papyrus grecs d'époque byzantine.

The most comprehensive edition at the present time is by Jean-Luc Fournet, who in 1999 published 51 Dioscorian poems and fragments (including 2 that he considered of dubious authenticity).

[52] In addition to the texts and commentaries offered by Maspero, Heitsch, Fournet, and the initial editors of other poems, a comprehensive study of his poetry was published by Leslie MacCoull in 1988: Dioscorus of Aphrodito: His Work and His World (Berkeley).

[53] A more positive assessment was offered by Leslie MacCoull, who insisted that a reader must take Dioscorus's Coptic background into consideration when reading the poetry.

[55] Clement Kuehn, however, proposed that the poems be viewed not from a Classical, Hellenistic, or even a strictly Egyptian perspective,[56] but through a lens of Byzantine culture and spirituality, in which Dioscorus and the Thebaid were so deeply immersed.

Kuehn demonstrated that the poems fit neatly and masterfully into the allegorical style that was pervasive in the pictorial art and literature of the Early Byzantine Era.

6th century representation of the Mother of God as a Byzantine Empress.

6th century representation of the Empress Theodora.