Diplomacy in the ancient Near East

A limited number of texts allow us to understand relatively well the contemporary diplomatic practices of certain decades, spread out across more than two millennia and large geographical distances.

Diplomatic relations have existed for as long as human communities have been organized into political units, which precedes the period of this study.

The first surviving documents on the subject of international relations appear towards the end of the Early Dynastic period of ancient Mesopotamia (2600-2340 B.C.E.).

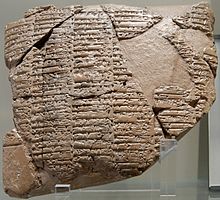

There is a tablet which is inscribed with a peace treaty concluded between Naram-Sin of Akkad (Sargon's grandson) and the king of Awan, in southwest Iran, who was his vassal.

They combined their military expeditions onto the Iranian plateau with matrimonial politics, marrying their daughters to the kings of the regions (Anshan, Zabshali) in order to win their loyalty and solidify their own legitimacy.

This allowed the gradual formation of more and more powerful and stable states, which dominated the international stage, and controlled a certain number of vassals, which tended to reduce over time.

In Syria, the dominant kingdom was that of Yamkhad (Aleppo), which profited from the dissipation of its neighbors Mari and Qatna (its greatest rival) over the course of the 18th and 17th centuries.

At the same time, the Hurrians began to found increasingly powerful political entities, culminating in the formation of the kingdom of Mitanni.

The diplomatic practices of this period are known thanks to several collections of exceptional importance: those of Hattusa, the Hittite capital (letters, diplomatic accords, historical chronicles), the letters of Amarna, in Egypt (international correspondence of the pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaton), and the royal archives of Ugarit, a minor Syrian kingdom controlled first by Egypt and later by the Hittites.

Assyria was the only one of these great kingdoms to preserve its power and political stability enough to rebuild an empire starting at the end of the 10th century.

Between 614 and 609, Assyria was destroyed by an alliance between the Babylonians and the Medes, but the empire of the former did not last even a full century, since their real power did not compare with that of the Medes— the Achaemenid Persians.

The different practices utilized in diplomatic relations in the ancient Near East are essentially known through the royal archives of the 2nd millennium, coming largely from four archaeological sites (Mari, Hattusa, Tell el-Amarna, and Ugarit), complemented by less numerous sources from the preceding millennium (Lagash, Ebla) and the following (Nineveh, Hebrew Bible).

Gradually, kings who didn't have suzerains (besides the gods) acquired a place apart, and in the second half of the second millennium they began to take the title of "great king" (šarru rābu), and formed a sort of very close "club" (to use the expression of H. Tadmor, reused by M. Liverani),[12] which determined who could enter, as a function of their political successes.

These messengers were the key actors in diplomacy: they carried messages, gifts sent by their king, but were also empowered to negotiate potential political accords or future marriages between royal courts.

As they have clothed all the Yamkhadians, while not having done so for the secretaries, servants of my master, I told Sin-bel-aplim (Babylonian official) on their behalf: 'Why this segregation on your part towards us, as if we were the sons of swine?

In order to allow the existence of proper relations between kings, without interpretive bias, written diplomatic tablets were required, of which many examples have been found at numerous archaeological sites.

These messages were generally written in Babylonian Akkadian, the international language dating from the beginning of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., and begin in a very simple manner, with an introductory address naming the sender and the recipient (according to the common Akkadian formula ana X qibī-ma umma Y-ma: "to X say: ... thus spoke Y".

I swear by the god of my father how my heart was offended- the price of these horses now, here in Qatna, is 600 shekels- and you have given me 20 minas of tin.

This paradigm is summarized in a letter discovered at Mari, in which the king of Qatna complains to his counterpart in Ekallatum, because the latter had not sent him gifts of the same value as those which he had sent previously.

The king of Qatna explains that this type of protest must not normally be made (the rules being unspoken etiquette), but that in this case he was almost inclined to take it as an affront, and that other sovereigns, upon learning of the incident, would think that he had come away from the exchange weaker than before.

The goods exchanged often mirrored those one found in international commerce: Elam in the Amorrite period thus made presents of tin from the mines of the Iranian Plateau, as the king of Egypt in the Amarna era sent gold from Nubia, and that of Alashiya (without a doubt Cyprus) offered copper.

Some believe that it amounted to disguised commerce, the contra-gift being the "price" paid for the gift, but this is debatable to the extent to which the desire for reciprocity remained present and dominant in these negotiations.

Exchanges of diplomatic presents could concern other objects, notably artisanal works, but also exotic animals, or of course fine horses.

[20] In the era of Amarna, Tushratta of Mitanni sent the statue of the goddess Ishtar from Nineveh to Egypt, possibly to appease the pharaoh Amenhotep III.

At particular times, states could conclude diplomatic accords, of which the names varied (for example, in Akkadian niš ili(m), riksu(m), māmītu(m), or adê in the neo-Assyrian era; lingaiš- or išhiul- in Hittite; bêrit in Hebrew).

[23] In the Amorrite period, many tablets detailing the protocols of oaths of alliance between kings were unearthed at Mari, Tell Leilan, and Kültepe, or are of unknown provenance (accords between Shadlash and Nerebtum and Eshnunna, Larsa and Uruk).

It is will good sentiments and complete sincerity that I make this oath before my gods, Shahmush and Addu, who is sworn to Zimri-Lim son of Yahdun-Lim king of Mari and the Bedouin country and that I meet him."

[32] Dynastic marriages were a very common diplomatic practice in the history of the ancient Near East, attested from the archives of Ebla in the archaic period, but above all documented in the 2nd millennium.

[35] In principle, every sovereign must play the game of matrimonial exchanges, but the Egyptian kings of the recent Bronze Age make an exception.

Envoys had to negotiate the dowry, but also to see the bride and assure the groom's family that she was beautiful, which was the main quality sought after in her.