Dissolution of Austria-Hungary

[citation needed] The Austro-Hungarian Empire had additionally been weakened over time by a widening gap between Hungarian and Austrian interests.

[2] Furthermore, a history of chronic overcommitment rooted in the 1815 Congress of Vienna in which Metternich pledged Austria to fulfill a role that necessitated unwavering Austrian strength and resulted in overextension.

The 1917 October Revolution and the Wilsonian peace pronouncements from January 1918 onward encouraged socialism on the one hand, and nationalism on the other, or alternatively a combination of both tendencies, among all peoples of the Habsburg monarchy.

The majority lived in a state of advanced misery by the spring of 1918, and conditions later worsened, for the summer of 1918 saw both the drop in food supplied to the levels of the 'turnip winter', and the onset of the 1918 flu pandemic that killed at least 20 million worldwide.

[4] As the Imperial economy collapsed into severe hardship and even starvation, its multi-ethnic army lost its morale and was increasingly hard-pressed to hold its line.

Furthermore, nationalists within the empire were becoming increasingly embittered as, under expanded wartime powers, the military routinely suspended civil rights and treated different national groups with varying degrees of contempt throughout the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy.

[5] At the last Italian offensive, the Austro-Hungarian Army took to the field without any food and munition supply and fought without any political supports for a de facto non-existent empire.

As the war went on the ethnic unity declined; the Allies encouraged breakaway demands from minorities and the Empire faced disintegration.

[7] As it became apparent that the Allied powers would win World War I, nationalist movements, which had previously been calling for a greater degree of autonomy for various areas, started pressing for full independence.

In the capital cities of Vienna and Budapest, the leftist and liberal movements and opposition parties strengthened and supported the separatism of ethnic minorities.

The military breakdown of the Italian front marked the start of the rebellion for the numerous ethnicities who made up the multiethnic Empire, as they refused to keep on fighting for a cause that now appeared senseless.

In response, Emperor Karl I agreed to reconvene the Imperial Parliament in 1917[dubious – discuss] and allow the creation of a confederation with each national group exercising self-governance.

On 14 October 1918, Foreign Minister Baron István Burián von Rajecz[8] asked for an armistice based on the Fourteen Points.

On 16 October 1918, Emperor Karl I of Austria and IV of Hungary proclaimed the People's Manifesto,[9][10] which envisaged to turn the Empire into a federal state of five Kingdoms (Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia and Polish-Galicia), in an attempt to take into account the aspirations of the Croats, Czechs, Austrian Germans, Poles, Ukrainians and Romanians without affecting the integrity of the lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen.

It also promised the unification of Polish lands via an Austro-Polish solution, and an Austro-Bohemian Compromise that would transform the projected Trialism into a proposal with two additional kingdoms.

The most prominent opponent of continued union with Austria, the pro-Entente pacifist Count Mihály Károlyi, seized power in the Aster Revolution on 31 October.

On the 1st of November, Károlyi's new Hungarian government decided to recall all of the troops who were conscripted from the territory of Kingdom of Hungary, which was a major blow for the Habsburg's armies on the front lines.

[20] By the end of October, there was nothing left of the Habsburg realm but its majority-German Danubian and Alpine provinces, and Karl I's authority was being challenged even there by the German-Austrian state council.

On 11 November, Karl I issued a carefully worded proclamation in which he recognized the Austrian people's right to determine the form of the state.

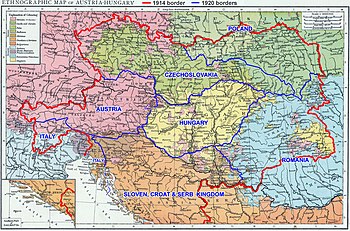

In regard to areas without a decisive national majority, the Entente powers ruled in many cases in favour of the newly-emancipated independent nation-states, enabling them to claim vast territories containing sizeable German- and Hungarian-speaking populations.

In the summer of 1919, Karl's cousin, Archduke Joseph August, became regent, but was forced to stand down after only two weeks when it became apparent the Allies would not recognise him or any other Habsburg as head of state.

[27] Finally, in March 1920, royal powers were entrusted to a regent, Miklós Horthy, who had been the last commanding admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy and had helped organize the counter-revolutionary forces.

In April 1919, Vorarlberg – the westernmost province of Austria – voted by a large majority to join Switzerland; however, both the Swiss and the Allies disregarded this result.

Prominent examples are the regions of Lombardy and Veneto in Italy, Silesia in Poland, most of Belgium and Serbia, and parts of northern Switzerland and southwestern Germany.