Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia[2] (/ˌtʃɛkoʊsloʊˈvæki.ə, ˈtʃɛkə-, -slə-, -ˈvɑː-/ ⓘ CHEK-oh-sloh-VAK-ee-ə, CHEK-ə-, -slə-, -VAH-;[3][4] Czech and Slovak: Československo, Česko-Slovensko)[5][6] was a landlocked country in Central Europe,[7] created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary.

In 1939, after the outbreak of World War II, former Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš formed a government-in-exile and sought recognition from the Allies.

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reestablished under its pre-1938 borders, with the exception of Carpathian Ruthenia, which became part of the Ukrainian SSR (a republic of the Soviet Union).

A period of political liberalization in 1968, the Prague Spring, ended when the Soviet Union, assisted by other Warsaw Pact countries, invaded Czechoslovakia.

Palacký supported Austro-Slavism and worked for a reorganized federal Austrian Empire, which would protect the Slavic speaking peoples of Central Europe against Russian and German threats.

With Edvard Beneš and Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Masaryk visited several Western countries and won support from influential publicists.

Czechoslovakia was founded in October 1918, as one of the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I and as part of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

[citation needed] This policy led to unrest among the non-Czech population, particularly in German-speaking Sudetenland, which initially had proclaimed itself part of the Republic of German-Austria in accordance with the self-determination principle.

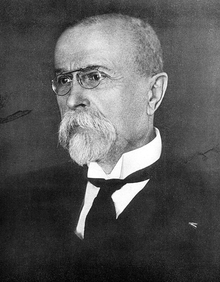

Under Tomas Masaryk, Czech and Slovak politicians promoted progressive social and economic conditions that served to defuse discontent.

Foreign minister Beneš became the prime architect of the Czechoslovak-Romanian-Yugoslav alliance (the "Little Entente", 1921–38) directed against Hungarian attempts to reclaim lost areas.

[21] The increasing feeling of inferiority among the Slovaks,[22][failed verification] who were hostile to the more numerous Czechs, weakened the country in the late 1930s.

[27] The deportation of Jews to concentration camps was organized under the direction of Reinhard Heydrich, and the fortress town of Terezín was made into a ghetto way station for Jewish families.

Heydrich's successor, Colonel General Kurt Daluege, ordered mass arrests and executions and the destruction of the villages of Lidice and Ležáky.

Under the authority of Karl Hermann Frank, German minister of state for Bohemia and Moravia, some 350,000 Czech laborers were dispatched to the Reich.

Most of the Czech population obeyed quiescently up until the final months preceding the end of the war, while thousands were involved in the resistance movement.

Those who remained were collectively accused of supporting the Nazis after the Munich Agreement, as 97.32% of Sudeten Germans had voted for the NSDAP in the December 1938 elections.

Although they would maintain the fiction of political pluralism through the existence of the National Front, except for a short period in the late 1960s (the Prague Spring) the country had no liberal democracy.

[31] In the 1950s, Czechoslovakia experienced high economic growth (averaging 7% per year), which allowed for a substantial increase in wages and living standards, thus promoting the stability of the regime.

[32] In 1968, when the reformer Alexander Dubček was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, there was a brief period of liberalization known as the Prague Spring.

This resistance involved a wide range of acts of non-cooperation and defiance: this was followed by a period in which the Czechoslovak Communist Party leadership, having been forced in Moscow to make concessions to the Soviet Union, gradually put the brakes on their earlier liberal policies.

The movement sought greater political participation and expression in the face of official disapproval, manifested in limitations on work activities, which went as far as a ban on professional employment, the refusal of higher education for the dissidents' children, police harassment and prison.

Pope John Paul II made a papal visit to Czechoslovakia on 21 April 1990, hailing it as a symbolic step of reviving Christianity in the newly-formed post-communist state.

After World War II, an active participant in Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), Warsaw Pact, United Nations and its specialized agencies; signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

After World War II, the economy was centrally planned, with command links controlled by the communist party, similarly to the Soviet Union.

Tomáš Baťa, a Czech entrepreneur and visionary, outlined his ideas in the publication "Budujme stát pro 40 milionů lidí", where he described the future motorway system.

The most significant daily newspapers in these times were Lidové noviny, Národní listy, Český deník and Československá Republika.

Private ownership of any publication or agency of the mass media was generally forbidden, although churches and other organizations published small periodicals and newspapers.

The Czechoslovakia national football team was a consistent performer on the international scene, with eight appearances in the FIFA World Cup Finals, finishing in second place in 1934 and 1962.

Well-known football players such as Jan Koller, Pavel Nedvěd, Antonín Panenka, Milan Baroš, Tomáš Rosický, Vladimír Šmicer, Petr Čech, Ladislav Petráš, Marián Masný, Ján Pivarník, Ján Mucha, Róbert Vittek, Peter Pekarík, and Marek Hamšík were all born in Czechoslovakia.

Several accomplished professional tennis players including Jaroslav Drobný, Ivan Lendl, Jan Kodeš, Miloslav Mečíř, Hana Mandlíková, Martina Hingis, Martina Navratilova, Jana Novotná, Petra Kvitová, Daniela Hantuchová, Barbora Krejčíková, Markéta Vondroušová and Karolína Muchová were born in Czechoslovakia (or what became the Czech Republic in 1993).