Distributed control system

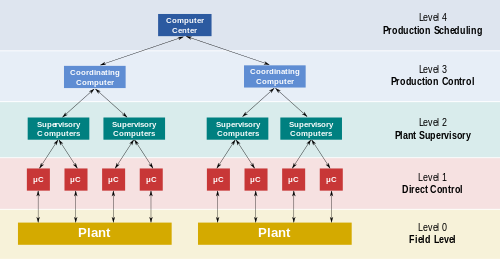

The DCS concept increases reliability and reduces installation costs by localizing control functions near the process plant, with remote monitoring and supervision.

Distributed control systems first emerged in large, high value, safety critical process industries, and were attractive because the DCS manufacturer would supply both the local control level and central supervisory equipment as an integrated package, thus reducing design integration risk.

This distributed topology also reduces the amount of field cabling by siting the I/O modules and their associated processors close to the process plant.

Effectively this was the centralisation of all the localised panels, with the advantages of lower manning levels and easier overview of the process.

It enabled sophisticated alarm handling, introduced automatic event logging, removed the need for physical records such as chart recorders, allowed the control racks to be networked and thereby located locally to plant to reduce cabling runs, and provided high level overviews of plant status and production levels.

The first industrial control computer system was built 1959 at the Texaco Port Arthur, Texas, refinery with an RW-300 of the Ramo-Wooldridge Company.

[4] In 1975, both Yamatake-Honeywell[5] and Japanese electrical engineering firm Yokogawa introduced their own independently produced DCS's - TDC 2000 and CENTUM systems, respectively.

The DCS largely came about due to the increased availability of microcomputers and the proliferation of microprocessors in the world of process control.

Function blocks continue to endure as the predominant method of control for DCS suppliers, and are supported by key technologies such as Foundation Fieldbus[9] today.

The central system ran 11 microprocessors sharing tasks and common memory and connected to a serial communication network of distributed controllers each running two Z80s.

Attention was duly focused on the networks, which provided the all-important lines of communication that, for process applications, had to incorporate specific functions such as determinism and redundancy.

The system installed at the University of Melbourne used a serial communications network, connecting campus buildings back to a control room "front end".

The first attempts to increase the openness of DCSs resulted in the adoption of the predominant operating system of the day: UNIX.

UNIX and its companion networking technology TCP-IP were developed by the US Department of Defense for openness, which was precisely the issue the process industries were looking to resolve.

The first DCS supplier to adopt UNIX and Ethernet networking technologies was Foxboro, who introduced the I/A Series[10] system in 1987.

The drive toward openness in the 1980s gained momentum through the 1990s with the increased adoption of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components and IT standards.

The introduction of Microsoft at the desktop and server layers resulted in the development of technologies such as OLE for process control (OPC), which is now a de facto industry connectivity standard.

Towards the end of the decade, the technology began to develop significant momentum, with the market consolidated around Ethernet I/P, Foundation Fieldbus and Profibus PA for process automation applications.

Fieldbus technics have been used to integrate machine, drives, quality and condition monitoring applications to one DCS with Valmet DNA system.

The initial proliferation of DCSs required the installation of prodigious amounts of this hardware, most of it manufactured from the bottom up by DCS suppliers.

Some suppliers that were previously stronger in the PLC business, such as Rockwell Automation and Siemens, were able to leverage their expertise in manufacturing control hardware to enter the DCS marketplace with cost effective offerings, while the stability/scalability/reliability and functionality of these emerging systems are still improving.

The life cycle of hardware components such as I/O and wiring is also typically in the range of 15 to over 20 years, making for a challenging replacement market.

Developed industrial economies in North America, Europe, and Japan already had many thousands of DCSs installed, and with few if any new plants being built, the market for new hardware was shifting rapidly to smaller, albeit faster growing regions such as China, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.