Divine Comedy Illustrated by Botticelli

[1][3] The manuscript eventually disappeared and most of it was rediscovered in the late nineteenth century, having been detected in the collection of the Duke of Hamilton by Gustav Friedrich Waagen, with a few other pages being found in the Vatican Library.

[4] Botticelli had earlier produced drawings, now lost, to be turned into engravings for a printed edition, although only the first nineteen of the hundred cantos were illustrated.

[4] Lippmann had moved swiftly and quietly, and when the sale was announced there was a considerable outcry in the British press and Parliament.

[7][8] Botticelli's attempt to design the illustrations for a printed book was unprecedented for a leading painter, and though it seems to have been something of a flop, this was a role for artists that had an important future.

[12] It is often thought that Botticelli's drawings were commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, an important patron of the artist.

The early 16th-century writer known as the Anonimo Magliabecchiano says that Botticelli painted a Dante on parchment for Lorenzo, but makes it sound as if this was a completed work.

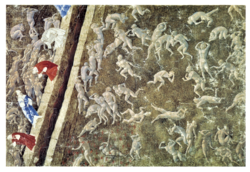

The entire thematic sequence of each canto was supposed to be illustrated by its own full-page drawing by Botticelli, an unprecedentedly ambitious conception.

Botticelli was combining this tradition with another, continuous narrative, where recurrent incidents were shown, usually unframed and in the margin below the text.

[3] The exact date of creation of the drawings is unknown but it is agreed that they were produced over a period of several years, and a stylistic development has been detected.

[17] Estimates vary between a start around the mid-1480s with the last approximately a decade later,[1] and a period extending between about 1480 and 1505 (by which time Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco was dead).

The earlier drawings for the Inferno are generally the most completed, and the most detailed,[20] but cantos II to VII, XI and XIV are missing, though probably made by Botticelli.

[21] The differing degrees of completion, and the canto numbers and first lines of the matching text inscribed on some sequences of pages but not others, all complicate understanding Botticelli's progress, and have been extensively debated.

The additional two illustrations of the Map of Hell and Lucifer lie outside this canto-text structure, thus providing an element of continuity which unifies the work.

[26] Lucifer's second drawing by Botticelli from Inferno XXXIV spans across two pages, and lies outside the text-illustration structure, unifying the narrative of the series.

The third round consists of the illustrations for cantos XV, XVI and XVII, which depict the punishment of those who sinned by violence against God, nature and art.

[24] Botticelli uses thirteen drawings to illustrate the eighth circle of Hell, depicting ten chasms that Dante and Virgil descend through a ridge.

[26]The Vatican Library has the drawing of the Map of Hell, and the illustrations for cantos I, IX, X, XII, XIII, XV and XVI of the Inferno.