Dmanisi hominins

Though their precise classification is controversial and disputed, the Dmanisi fossils are highly significant within research on early hominin migrations out of Africa.

The taxonomic status of the Dmanisi hominins is somewhat unclear due to their small brain size, primitive skeletal architecture, and the range of variation exhibited between the skulls.

Later analyses by the Dmanisi research team have concluded that all the skulls likely represent the same taxon with significant age-related and sexual dimorphism, though this is not a universally held view.

The Dmanisi fossil site was located near an ancient lake shore, surrounded by forests and grasslands and home to a diverse fauna of Pleistocene animals.

The Georgian Paleobiological Institute of the Academy of Sciences was informed immediately and systematic palaeontological excavations began in 1983, but ended in 1991 on account of financial issues.

[11][12] As the heads of the expedition, Georgian archaeologists and anthropologist Abesalom Vekua and David Lordkipanidze (then in Tbilisi) were summoned to the site and on the next morning, the mandible was freed from the rock around it, a complicated process that took nearly an entire day.

The discovery of the two skulls was highly publicised in international media and the Georgian fossils were for the first time widely acknowledged as the earliest known hominins outside of Africa.

[4] The classification of the Dmanisi hominins is disputed and a discussion on whether they represent an early form of H. erectus, a distinct species of their own dubbed H. georgicus or something else entirely are ongoing.

The D211 mandible was described in 1995 by Gabunia and Vekua, who classified it as belonging to a basal population of H. erectus based on dental similarity especially with African specimens (sometimes called H.

[36] In 1998, palaeoanthropologists Antonio Rosas and José Bermúdez De Castro pointed out that such a mosaic anatomy is also documented in H. ergaster, and suggested the classification Homo sp.

Rightmire, Lordkipanidze and Vekua concluded that if some of the H. habilis-like traits, such as the size, cranial capacity and parts of the facial morphology, were considered plesiomorphic and primitive retentions, there would be no reason to exclude Skulls 1 to 4 from H.

[45] A 2006 comparative analysis of D211 and D2600 by palaeoanthropologists Matthew M. Skinner, Adam D. Gordon and Nicole J. Collard found that the degree of dimorphism expressed between the two mandibles was greater than expected in modern great apes and human, as well as in other extinct hominin species.

[49] A 2008 analysis of the teeth of Skulls 2 and 3 and the D2600 mandible by Lordkipanidze, Vekua and palaeoanthropologists María Martinón-Torres, José María Bermúdez de Castro, Aida Gómez-Robles, Ann Mergvelashvili and Leyre Prado found that like other parts of the fossils, the teeth too showed a combination of primitive Australopithecus- and H. habilis-type traits and more derived H. erectus-type traits.

[8] Lordkipanidze and colleagues interpreted Skull 5 as part of the same population as the rest of the Dmanisi fossils, as they came from the same general time and place, and had a range of variation similar to what is exhibited in chimpanzee, bonobo and modern human samples.

[53] Palaeoanthropologists Jeffrey H. Schwartz, Ian Tattersall and Zhang Chi responded to Lordkipanidze and colleagues in 2014, disagreeing with the idea that all five skulls were from the same species.

The results of the analysis, which compared the skulls to many specimens of both H. erectus and H. habilis somewhat questioned the current recognition of species-level diversity in early Homo in so far that the Dmanisi hominins were found to broadly share many similarities with both species.

[57] This led the researchers to hypothesize that H. erectus and H. habilis constitute a single evolutionary lineage which emerged in Africa and later spread throughout Eurasia.

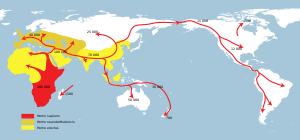

Before the discovery of the Dmanisi skulls, the earliest known hominin fossils in Europe and Asia were either too incomplete and fragmentary to be reliably identified at the species level or exhibited morphological traits specific to the region where they were recovered.

[61] The Pleistocene sediments at Dmanisi are deposited directly atop a thick layer of volcanic rock that has been radiometrically dated to 1.85 million years old.

[65] There are several features that distinguish the Dmanisi hominins from early Homo such as H. habilis, including the well-developed brow ridge, sagittal keels, large orbits, the premolar teeth in the upper jaw having single roots and the angulation of the cranial vault.

Based on the skulls and the postcranial material, the Dmanisi hominins appears to have been small-brained individuals with prominent brow ridges, and stature, body mass and limb proportions at the lower range limit of modern human variation.

[20] Through calculations based on the size of their limb bones and a humerus (no complete skeleton has yet been recovered), the Dmanisi individuals were approximately 145–166 cm (4.8–5.4 ft) tall and weighed about 40–50 kg (88–110 lbs).

This might indicate that the evolution of improved walking and running performance was not a sudden change, but a continual process throughout the Early and Middle Pleistocene.

[68] Humeral torsion (the angle formed between the proximal and distal articular axis of the humerus) influences the range of movement and the orientation of the arms relative to the torso.

The fossil vertebrae recovered at Dmanisi show lumbar lordosis, the orientation of the facet joints suggests that the range of spinal flexion in the Dmanisi hominins was comparable to modern humans and the relatively large cross-sectional areas of the vertebrae indicates resistance to increased compressive loads, suggesting that the hominins were capable of running and long-range walking.

In the Dmanisi hominins, the feet would have been oriented more medially (closer together) and load would have been distributed more evenly over the rays (metatarsals and toes) than in modern humans.

[74] Animal fossils recovered in the same sediments as the hominin remains demonstrate that Pleistocene Dmanisi would have been home to a highly diverse fauna,[31] including pikas,[73] lizards, hamsters, tortoises, hares, jackals and fallow deer.

[10] Most of the animals found are Villafranchian (a European land mammal age) mammals and several extinct species are represented, including Megantereon megantereon and Homotherium crenatidens (both saber-toothed cats), Panthera gombaszoegensis (the European jaguar), Ursus etruscus (the Etruscan bear), Equus stenonis (the Stenon zebra), Stephanorhinus etruscus (the Etruscan rhinoceros), Pachystruthio dmanisensis (the giant ostrich), deer Cervus perrieri and Cervidae cf.

The abundance of Boraginaceae seeds, often taken in later sites as an indication of human occupation, could mean that hominins were already having an impact on local flora at this early time.

[77] In addition to the tools found at the site, many unmodified stones that must have originated elsewhere on account of their mineralogical composition (meaning they had not arrived there naturally, but had been brought by hominins) have also been recovered.