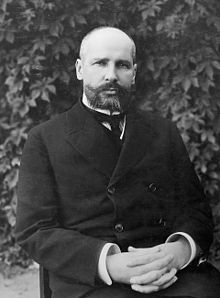

Dmitrii Bogrov

Raised in a wealthy Jewish family in Kyiv, Bogrov developed sympathies for revolutionary socialism from an early age and became involved with the Ukrainian anarchist movement while studying law at university.

After graduating, he moved to Saint Petersburg in order to practice law and seek safety from the rising environment of antisemitism in the Russian Empire.

He told the Okhrana that assassins were planning to kill a government official, convincing them to grant him a ticket to the Kyiv Opera House, where the prime minister was due to attend a play.

[5] The Bogrov family was deeply involved in left-wing politics: Dmitrii's cousin was a member of the Bolsheviks,[6] while his father supported the left of the Constitutional Democratic Party.

[6] He came to identify himself as an "anarchist-individualist",[9] as he resented formal organisation, rejected conventional morality and believed revolutionaries ought to operate alone under their own direction, even once declaring "I am my own party".

[12] Although his father paid for his education and provided him with a generous allowance,[13] Bogrov started to experience financial difficulties due to his gambling habit.

[18] Many the group's members were imprisoned or deported to Siberia during this period,[19] including its leaders Herman Sandomirskyi [uk] and Naum Tysh,[20] although it's uncertain how many of these were due to Bogrov's reports.

[21] In July of that year, Bogrov supplied the Okhrana with information about the bomb-manufacturing activities of the Maximalists, although he would later claim that he deliberately kept the exact address from them in order to prevent a police raid from taking place.

Bogrov himself took the opportunity to go abroad, where he told the editor of an anarchist newspaper that either Tsar Nikolai II or prime minister Pyotr Stolypin ought to be assassinated.

[25] But this time, he provided the police with unvaluable and even fabricated information,[24] later claiming he did this "for revolutionary purposes, so that I could make close contacts in these institutions and learn how they work.

[41] In late August, he went to the Okhrana and told them that revolutionaries by the names of "Nikolai Iakovlevich" and "Nina Aleksandrovna" intended to assassinate a member of the government during the Tsar's upcoming visit to the city, claiming they had a bomb and were staying at his flat.

[42] Convinced of his reliability due to his past work as an informant, the Okhrana gave him a pass to attend the events, so that he could identify and apprehend the assassin.

He was provided with a ticket to a performance of The Tale of Tsar Saltan at the Kyiv Opera House, where Stolypin was due to attend and where Bogrov claimed the assassin planned to carry out his attack.

[50] In order to pre-empt such a pogrom from taking place, Kyiv's Jewish community denounced Bogrov's actions and held a special service wishing health for the Tsar's family and to Stolypin.

[5] In his final words to Aleskhovskii, Bogrov asked him: "Please tell the Jews that I did not want to harm them in any way, on the contrary, I struggle for their good and for the happiness of the Jewish people.

[70] The most common explanation for the assassination is that Bogrov was motivated by the threats against his life by the revolutionary anarchist group, a version which is supported by historians Abraham Ascher,[71] Anna Geifman,[72] George Tokmakoff,[36] and Jonathan Daly.

[76] American historian Paul Avrich also considered the assassination to have been a "personal act" by Bogrov, rather than having been influenced by his associations with the police or revolutionary groups.

[77] In his historical fiction novel The Red Wheel, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn suggested that Bogrov was motivated by protecting the interests of his Jewish family against rising Russian nationalism.

[78] The 2012 Russian docu-drama Stolypin: A Shot at Russia likewise highlighted Bogrov's Jewish background as a motivation for the assassination, while also portraying his character as a gambler and insect collector.

[79] This "Jewish motivation" has been disputed by Ascher and Geifman,[75] as well as Simon Dixon,[80] who each highlighted the assimilation of Bogrov's family into the Russian elite.

[84] Yakov Protazanov's 1928 film The White Eagle also makes allusions to the culpability of the Tsarist government in Bogrov's assassination of Stolypin.