Do Ho Suh

As a result, Suh pays particular attention to the site-specificity of the work, and sensorial experience of the viewer engaging with his pieces while moving in the exhibition space.

[4]: 29 His material choices of rice paper, and fabric commonly found in hanbok also refer to traditional Korean art and architecture.

The Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles commissioned Suh to create the installation, leading him to begin exploring the question of home through his work.

The installation features a 1:1 replica of Suh's childhood home in Korea, including both the main structure and fixtures like toilets, radiators, and kitchen appliances.

For Suh, this continual renaming allows the work to hold the traces of each space it traverses, and thus reshape the viewer's notion of what a home is.

The movement of the work also allows Suh to carry his childhood memories with him no matter where he goes, therefore making it possible for him to shrink the distance between where he came from and is at the present.

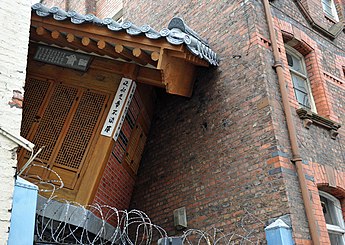

Suh links his work with what he describes as the porosity of Korean architecture, exemplified by the doors and windows that exist in lieu of walls, and translucent rice paper that covers them.

The site-specific installation raised the floor of the gallery, inviting viewers to walk on the forty glass panels supported by 180,000 cast plastic human figures.

The installation features high-school yearbook photos from Korea from over three decades of graduating classes juxtaposed together, and printed on sheets of paper pasted to the wall.

While Suh does acknowledge that his pieces do engage with the concept, he foregrounds their role in shaping a viewer's experience of space, and considers the tendency of ascribe individuality to the West and collectivity to the East to be reductive.

The next chapter, Fallen Star: A New Beginning (1/35th Scale) (2006) reveals that the house has crashed into the Providence building Suh lived in during his RISD days.

[11] The work both references a specific film (The Wizard of Oz), and explores the relationship between the viewer and cinematic space with a 1:5 scale model of Suh's childhood in Korea colliding with a similarly sized replica of his Providence apartment.

The installation features a blue cottage suspended at an angle on the top of the Jacobs School of Engineering on the La Jolla campus of the University of California, San Diego.

Those who enter will find the angle of the floor and house are mismatched, and the interior is furnished with pictures of families, including Suh's, on the wall, as well as an array of knickknacks typically found inside a home.

[6] Suh worked with his team to produce a rubbing of the interior of a local theater troupe's former house while blindfolded, relying on only touch to create the piece.

After a number of failed attempts to make larger-scale works, an intern at the Institute suggested that Suh use gelatine paper.

Suh has described the pleasure of ceding total control over the work due the contingency of the threading with the sewing machine, and paper shrinkage.

Critics and curators writing about Suh's work often draw connections between his installations and personal background as part of the Korean diaspora.

[17]: 14 However, art historians Miwon Kwon and Joan Kee have critiqued the narrowness of this interpretation of Suh's practice, complicating the readings of his work that view them as representative of a global itinerancy.

She argues that these critics view the culturally specific aspects as secondary, and paradoxically utilize them in order to find the commonality of itinerancy.

"[18]: 23 Joan Kee argues that Suh's work gestures to the unknowability of the home, making his installations recreating his previous residences perpetually materially and conceptually unresolved.

Rose argues that Suh's use of different materials both pulls his re-creations away from indexicality, and draws them towards the fundamental issues of representation and space in the field of architecture.

Rose asserts that Suh's work acts as a reminder that architecture is not inherently symbolic, but rather gains its meaning through human interaction.

[21]: 142 Curator and critic Chung Shinyoung identifies the antimodernist devices of literariness and theatricality in Suh's Speculation Project, but questions if there is anything more to the work to justify its dramatization of allegorical fiction beyond spectacle and the artist's indulgence.