Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

[8] By the early 1940s, the foundation had accumulated such a large collection of avant-garde paintings that the need for a permanent museum was apparent,[14] and Rebay wanted to establish it before Guggenheim died.

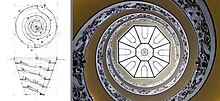

[20] It took him 15 years, more than 700 sketches and six sets of working drawings to create and complete the museum, after a series of difficulties and delays;[21][22] the cost eventually doubled from the initial estimate.

"[24][25] Critic Paul Goldberger later wrote that Wright's modernist building was a catalyst for change, making it "socially and culturally acceptable for an architect to design a highly expressive, intensely personal museum.

[35] Instead, in March 1944, Rebay and Guggenheim acquired a site on Manhattan's Upper East Side, at the corner of 89th Street and the Museum Mile section of Fifth Avenue, overlooking Central Park.

[73][76] Wright opened an office in New York City to oversee the construction, which he felt required his personal attention, and appointed his son-in-law William Wesley Peters to supervise the day-to-day work.

"[104] He had staged a smaller sculpture exhibition the previous year, where he learned how to compensate for the space's unusual geometry by constructing special plinths at a particular angle, but this was impossible for one piece, an Alexander Calder mobile whose wire inevitably hung at a true plumb vertical.

[113] To accommodate the expanding collection, in 1963, the Guggenheim announced plans for a four-story annex,[114] which the New York City Board of Standards and Appeals approved the next year.

[152][153] The SoHo building's exhibits included Marc Chagall and the Jewish Theater, Paul Klee at the Guggenheim Museum, Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective and Andy Warhol: The Last Supper.

[187] After architects and engineers determined that the building was structurally sound, renovations began in September 2005 to repair cracks and modernize systems and exterior details.

[193] The renovation cost $29 million and was funded by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation's board of trustees, the city's Department of Cultural Affairs, the New York state government and MAPEI Corporation.

[193][205] The New York Times said the Guggenheim Foundation had selected him because his "calmer, steadier presence" contrasted with the "nearly 20 often tumultuous years of Mr. Krens's maverick vision".

[211][212] She accused the museum of racism and alleged that, among other things, officials withheld resources and refused to let journalists interview her, though an article in The Atlantic described LaBouvier as being hostile toward people who commented on her exhibition.

[234] Wright described a symbolic meaning to the building's shapes: "[T]hese geometric forms suggest certain human ideas, moods, sentiments – as for instance: the circle, infinity; the triangle, structural unity; the spiral, organic progress; the square, integrity.

[243] The main gallery rises above the southern part of the bridge; it consists of a "bowl"-shaped massing, with several concrete "bands" separated by recessed aluminum skylights.

This wing was made of concrete, with relief carvings of squares and octagons on its facade, and housed the museum's library, storage space and the Thannhauser Gallery.

[258] To the south of the main entrance is a small circular vestibule, which contains a floor with metal arcs and a low plaster ceiling with recessed lighting.

[89][263] Wright's design differed from the conventional approach to museum layout, in which visitors pass through a series of interconnected rooms and retrace their steps when exiting.

[265] The ramp, made of reinforced concrete, ascends at a 5 percent slope[84][239] from ground level and rises one story, where it wraps around a planter and passes through a double-height archway.

[270] Later in the design, Wright added a dozen concrete ribs along the walls of the main gallery, which both provide structural reinforcement and divide the ramp into sections.

[304][305] Its earliest works include modernists such as Rudolf Bauer, Rebay, Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Amedeo Modigliani and Pablo Picasso.

[307] Pieces such as Chagall's Green Violinist,[308] Franz Marc's Yellow Cow,[309] Jean Metzinger's Woman with a Fan,[310] and Picasso's The Accordionist[102] are also part of the founding collection.

[320][321] Under Sweeney's tenure, in the 1950s, the Guggenheim acquired Brâncuși's Adam and Eve (1921)[13][322] and works by other modernist sculptors such as Joseph Csaky, Jean Arp, Calder, Alberto Giacometti and David Smith.

[13][323] Sweeney reached beyond the 20th century to acquire Paul Cézanne's Man with Crossed Arms (c. 1899)[13] and works by David Hayes, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock.

[330] In 2007, the heirs of Berlin banker Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy requested the restitution of the Picasso painting "Le Moulin de la Galette" (1900), which they claimed he had sold under duress by the Nazis.

[355] Emily Genauer of the New York Herald Tribune said the building had been likened to "a giant corkscrew, a washing machine and a marshmallow",[356] while Solomon's niece Peggy Guggenheim believed it resembled "a huge garage".

[360] John Canaday of The New York Times wrote that the design would be worthy of merit if it were "stripped of its pictures",[361][362] while Hilton Kramer of Arts Magazine opined that the structure was "what is probably [Wright's] most useless edifice".

[363] Architectural critic Lewis Mumford summed up the opprobrium: Wright has allotted the paintings and sculptures on view only as much space as would not infringe upon his abstract composition.

[371][372] Marcus Whiffen and Frederick Koeper wrote: "The dynamic interior of the Guggenheim is, for some, too competitive for the display of art, but no one disputes that it is one of the memorable spaces in all of architecture.

[376][377] The American Institute of Architects gave a Twenty-five Year Award to the Guggenheim in 1986, describing the museum's building as "an architectural landmark and a monument to Wright's unique vision".

[389][390] The American Institute of Architects' 2007 survey List of America's Favorite Architecture ranked the Guggenheim Museum among the top 150 buildings in the United States.