Domesday Book

[4] Richard FitzNeal wrote in the Dialogus de Scaccario (c. 1179) that the book was so called because its decisions were unalterable, like those of the Last Judgment, and its sentence could not be quashed.

Other areas of modern London were then in Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, and Essex and have their place in Domesday Book's treatment of those counties.

Tenants-in-chief included bishops, abbots and abbesses, barons from Normandy, Brittany, and Flanders, minor French serjeants, and English thegns.

The richest magnates held several hundred manors typically spread across England, though some large estates were highly concentrated.

Manors were generally listed within each chapter by the hundred or wapentake (in eastern England), the second tier of local government under the counties, in which they lay.

[clarification needed] Under the feudal system, the king was the only true "owner" of land in England by virtue of his allodial title.

Holdings of bishops followed, then of abbeys and religious houses, then of lay tenants-in-chief, and lastly the king's serjeants (servientes) and thegns.

Sir Michael Postan, for instance, contends that these may not represent all rural households, but only full peasant tenancies, thus excluding landless men and some subtenants (potentially a third of the country's population).

[14] Apart from the wholly rural portions, which constitute its bulk, Domesday contains entries of interest concerning most towns, which were probably made because of their bearing on the fiscal rights of the crown therein.

Georges Duby indicates this means a mill for every forty-six peasant households and implies a great increase in the consumption of baked bread in place of boiled and unground porridge.

[20] The word "doom" was the usual Old English term for a law or judgment; it did not carry the modern overtones of fatality or disaster.

[21] Richard FitzNeal, treasurer of England under Henry II, explained the name's connotations in detail in the Dialogus de Scaccario (c.1179):[22] The natives call this book "Domesday", that is, the day of judgement.

[23] Either through false etymology or deliberate word play, the name also came to be associated with the Latin phrase Domus Dei ("House of God").

What is believed to be a full transcript of these original returns is preserved for several of the Cambridgeshire Hundreds – the Cambridge Inquisition – and is of great illustrative importance.

[29] The Exon Domesday (named because the volume was held at Exeter) covers Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, and one manor of Wiltshire.

These were mainly: After a great political convulsion such as the Norman Conquest, and the following wholesale confiscation of landed estates, William needed to reassert that the rights of the Crown, which he claimed to have inherited, had not suffered in the process.

Historians believe the survey was to aid William in establishing certainty and a definitive reference point as to property holdings across the nation, in case such evidence was needed in disputes over Crown ownership.

It is evident that William desired to know the financial resources of his kingdom, and it is probable that he wished to compare them with the existing assessment, which was one of considerable antiquity, though there are traces that it had been occasionally modified.

The great bulk of Domesday Book is devoted to the somewhat arid details of the assessment and valuation of rural estates, which were as yet the only important source of national wealth.

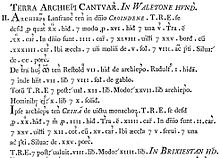

After stating the assessment of the manor, the record sets forth the amount of arable land, and the number of plough teams (each reckoned at eight oxen) available for working it, with the additional number (if any) that might be employed; then the river-meadows, woodland, pasture, fisheries (i.e. fishing weirs), water-mills, salt-pans (if by the sea), and other subsidiary sources of revenue; the peasants are enumerated in their several classes; and finally the annual value of the whole, past and present, is roughly estimated.

This was of great importance to William, not only for military reasons but also because of his resolve to command the personal loyalty of the under-tenants (though the "men" of their lords) by making them swear allegiance to him.

As Domesday Book normally records only the Christian name of an under-tenant, it is not possible to search for the surnames of families claiming a Norman origin.

[33] Domesday Book was preserved from the late 11th to the beginning of the 13th centuries in the royal Treasury at Winchester (the Norman kings' capital).

[38] In 1918–19, prompted by the threat of German bombing during the First World War, they were evacuated (with other Public Record Office documents) to Bodmin Prison, Cornwall.

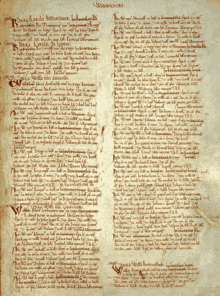

[41][42] The project to publish Domesday was begun by the government in 1773, and the book appeared in two volumes in 1783, set in "record type" to produce a partial-facsimile of the manuscript.

[47] As H. C. Darby noted, anyone who uses Domesday Book can have nothing but admiration for what is the oldest 'public record' in England and probably the most remarkable statistical document in the history of Europe.

And the geographer, as he turns over the folios, with their details of population and of arable, woodland, meadow and other resources, cannot but be excited at the vast amount of information that passes before his eyes.

[48]The author of the article on the book in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica noted, "To the topographer, as to the genealogist, its evidence is of primary importance, as it not only contains the earliest survey of each township or manor, but affords, in the majority of cases, a clue to its subsequent descent."