Domestic violence against men

[5][6][7] Men who report domestic violence can face social stigma regarding their perceived lack of machismo or other denigrations of their masculinity,[1]: 6 [8] the fear of not being believed by authorities, and being falsely accused of being the perpetrator.

[11][12] Intimate partner violence against men is a controversial area of research, with terms such as gender symmetry, battered husband syndrome and bidirectional IPV provoking debate.

[17] Determining the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV) against males can be difficult, as men may be reluctant to report their abuse or seek help.

[20] Supplementary studies carried out in 2001 and from 2004 onwards have consistently recorded significantly higher rates of intimate partner violence (committed against both men and women) than the standard crime surveys.

A recent research paper by Dr. Elizabeth Bates from the University of Cumbria found that a common experience for male intimate partner violence victims was that no one believed them, or were responded to by laughter, including the police.

These reports have consistently recorded significantly higher rates of both male and female victims of intimate partner violence than the standard crime surveys.

An example might be a recent survey from Canada's national statistical agency that concluded that "equal proportions of men and women reported being victims of spousal violence during the preceding 5 years (4% respectively).

[27] It is very common for men to avoid reporting or admitting to cases of domestic violence due to various reasons, such as fear of ridicule, embarrassment, and the lack of support.

[42] Parts of support services, especially family protection and child welfare, do not recognise that men can be victim and/or do not understand the psychological control that they may be under due to their partner.

[61][62] In England and Wales, the 1995 "Home Office Research Study 191" found that in the twelve months prior to the survey, 4.2% of both men and woman between the ages of 16 and 59 had been assaulted by an intimate.

[35] From 2010 to 2012, scholars of domestic violence from the U.S., Canada and the U.K. assembled The Partner Abuse State of Knowledge, a research database covering 1700 peer-reviewed studies, the largest of its kind.

They also stated if one examines who is physically harmed and how seriously, expresses more fear, and experiences subsequent psychological problems, domestic violence is significantly gendered toward women as victims.

– discuss] An especially controversial aspect of the gender symmetry debate is the notion of bidirectional or reciprocal intimate partner violence (i.e. when both parties commit violent acts against one another).

Findings regarding bidirectional violence are particularly controversial because, if accepted, they can serve to undermine one of the most commonly cited reasons for female perpetrated IPV; self-defense against a controlling male partner.

[69] A study conducted in 2007 by Daniel J. Whitaker, Tadesse Haileyesus, Monica Swahn, and Linda S. Saltzman, of 11,370 heterosexual U.S. adults aged 18 to 28 found that 24% of all relationships had some violence.

[70][71] In 1997, Philip W. Cook conducted a study of 55,000 members of the United States Armed Forces, finding bidirectionality in 60-64% of intimate partner violence cases, as reported by both men and women.

"[78] In a 2002 review of the research presenting evidence of gender symmetry, Michael Kimmel noted that more than 90% of "systematic, persistent, and injurious" violence is perpetrated by men.

[59][81] For example, the National Institute of Justice cautions that the CTS may not be appropriate for intimate partner violence research at all "because it does not measure control, coercion, or the motives for conflict tactics".

[79][17] Barbara J. Morse and Malcolm J. George have presented data suggesting that male underestimation of their partner's violence is more common in CTS based studies than overestimation.

Another critic, Kersti Yllö, who holds Straus and those who use the CTS accountable for damaging the gains of the battered women's movement, by releasing their findings into the "marketplace of ideas".

She argues that, as sociologists committed to ending domestic violence, they should have foreseen the controversy such statistics would cause and the damage it could potentially do to battered women.

In reaction to the findings of the U.S. National Family Violence Survey in 1975,[4] Suzanne K. Steinmetz wrote an article in 1977 in which she coined the term as a correlative to "battered wife syndrome".

[57]: 505 [92] According to Malcolm J. George, Steinmetz' article "represented a point of departure and antithetical challenge to the otherwise pervasive view of the seemingly universality of female vulnerability in the face of male hegemony exposed by the cases of battered wives".

Steinmetz' claims in her article, and her use of the phrase "battered husband syndrome" in particular, aroused a great deal of controversy, with many scholars criticizing research flaws in her work.

[96][97] Juan Carlos Ramírez explains that given the socially accepted model of femininity as one of submission, passivity and abnegation, whatever behavior does not follow this stereotype will be perceived in an exaggerated manner as abnormal and violent.

[99] In a five-year study of 978 college students from California, concluded in 1997, Martin S. Fiebert and Denise M. Gonzalez found an intimate partner violence rate amongst women of 20%.

Illustrative of this fallacious single-cause approach are the state-mandated offender treatment programs that forbid treating other causes, such as inadequate anger management skills.

"[103] Other explanations for both male and female-perpetrated intimate partner violence include psychopathology, anger, revenge, skill deficiency, head injuries, biochemical imbalances, feelings of powerlessness, lack of resources, and frustration.

A 2012 review from the journal Psychology of Violence found that women suffered disproportionately as a result of IPV especially in terms of injuries, fear, and posttraumatic stress.

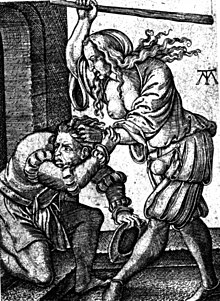

[116] Societal gender and marriage expectations were relevant in these discrepancies; many judges and newspaper articles joked that men subjected to intimate partner violence were "weak, pitiful, and effeminate.