Domestication of the dog

The domestication of the dog predates agriculture,[1] and it was not until 11,000 years ago in the Holocene era that people living in the Near East entered to relationships with wild populations of aurochs, boar, sheep, and goats.

[3] In 2021, a literature review of the current evidence infers that domestication of the dog began in Siberia 26,000-19,700 years ago by Ancient North Eurasians, then later dispersed eastwards into the Americas and westwards across Eurasia.

[20][21] The fossil record suggests that the earliest grey wolf specimens were found in what was once eastern Beringia at Old Crow, Yukon, in Canada and at Cripple Creek Sump, Fairbanks, in Alaska.

However, studies show that one or more of these ancient populations is more directly ancestral to dogs than are modern wolves, and conceivably these were more prone to domestication by the first humans to expand into Eurasia.

[1] In 2017, a study compared the nuclear genome (from the cell nucleus) of three ancient dog specimens and found evidence of a single dog-wolf divergence occurring between 36,900 and 41,500 YBP.

[42] In 2018, a literature review found that most genetic studies conducted over the last two decades were based on modern dog breeds and extant wolf populations, with their findings dependent on a number of assumptions.

[46] It was dated to 33,300 YBP, which predates the oldest evidence from Western Europe and the Near East[44] The mDNA analysis found it to be more closely related to dogs than wolves.

[50] One review considered why the domestication of the wolf occurred so late and at such high latitudes, when humans were living alongside wolves in the Middle East for the past 75,000 years.

The theory is that the extreme cold during one of these events caused humans to either shift their location, adapt through a breakdown in their culture and change of their beliefs, or adopt innovative approaches.

[5] When, where, and how many times wolves may have been domesticated remains debated because only a small number of ancient specimens have been found, and both archaeology and genetics continue to provide conflicting evidence.

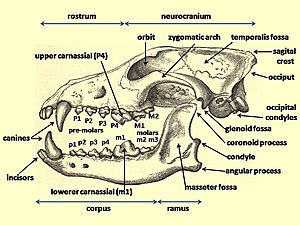

The skull shape, tooth wear, and isotopic signatures suggested these were specialist megafauna hunters and scavengers that became extinct while less specialized wolf ecotypes survived.

Calculations of the lipid content of arctic and subarctic game available across the cold steppe environment at this time and today shows that in order to gain the necessary quantity of fat and oils, there would have been enough excess animal calories to feed either proto-dogs or wolves with no need for competition.

This result suggests a common origin for dominant yellow in dogs and white in wolves but without recent gene flow, because this light colour clade was found to be basal to the golden jackal and genetically distinct from all other canids.

The evolution of the dietary metabolism genes may have helped process the increased lipid content of early dog diets as they scavenged on the remains of carcasses left by hunter-gatherers.

[26][49][78] A unique dietary selection pressure may have evolved both from the amount consumed, and the shifting composition of, tissues that were available to proto-dogs once humans had removed the most desirable parts of the carcass for themselves.

[26] A study of the mammal biomass during modern human expansion into the northern Mammoth steppe found that it had occurred under conditions of unlimited resources, and that many of the animals were killed with only a small part consumed or were left unused.

This raises the possibility that convergent evolution has occurred: both Canis familiaris and Homo sapiens might have evolved some similar (although obviously not identical) social-communicative skills – in both cases adapted for certain kinds of social and communicative interactions with human beings.

Today's wolves may even be less social than their ancestors, as they have lost access to large herds of ungulates and now tend more toward a lifestyle similar to coyotes, jackals, and even foxes.

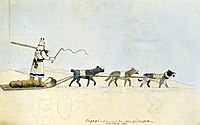

[27] In 2021, a review of the current evidence infers from the timings provided by DNA studies that the dog was domesticated in Siberia 23,000 years ago by ancient North Siberians.

Both species hunt the same prey, and their increased interactions may have resulted in the shared scavenging of kills, wolves drawn to human campsites, a shift in their relationship, and eventually domestication.

The sequences showed an increase in the population size approximately 23,500 YBP, which broadly coincides with the proposed genetic divergence of the ancestors of dogs from modern wolves.

[105] Dogs and wolves living in the Himalayas and on the Tibetan plateau carry the EPAS1 allele that is associated with high-altitude oxygen adaptation, which has been contributed by a ghost population of an unknown wolf-like canid.

Analyses of a recently sequenced genome from the Mesolithic site of Veretye, Karelia (~10,000 YBP) in Northeast Europe recapitulate findings that show these dogs possessed ancestry related to both Arctic (~70%) and Western Eurasian (~30%) lineages.

People living in the Lake Baikal region 18,000–24,000 YBP were genetically related to western Eurasians and contributed to the ancestry of Native Americans, however these were then replaced by other populations.

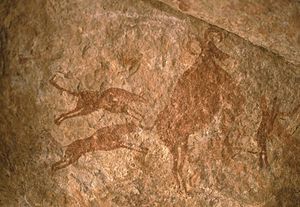

[118][119][120] Petroglyph rock art dating to 8,000 YBP at the sites of Shuwaymis and Jubbah, in northwestern Saudi Arabia, depict large numbers of dogs participating in hunting scenes with some being controlled on a leash.

[121] The transition from the Late Pleistocene into the early Holocene was marked by climatic change from cold and dry to warmer, wetter conditions and rapid shifts in flora and fauna, with much of the open habitat of large herbivores being replaced by forests.

[119][120] The dog's ability to chase, track, sniff out and hold prey can significantly increase the success of hunters in forests, where human senses and location skills are not as sharp as in more open habitats.

[4] In North America, the earliest dog remains were found in Lawyer's Cave on the Alaskan mainland east of Wrangell Island in the Alexander Archipelago of southeast Alaska, radiocarbon dating indicates 10,150 YBP.

[3] In 2015, a study mapped the first genome of a 35,000 YBP Pleistocene wolf fossil found in the Taimyr Peninsula, arctic northern Siberia and compared it with those of modern dogs and grey wolves.

[3] The oldest dog remains to be found in Africa date 5,900 YBP and were discovered at the Merimde Beni-Salame Neolithic site in the Nile Delta, Egypt.