Dominican art

[1] Going back to the origins of autochthonous art, corresponding to the stage known as prehistoric, primitive or pre-Hispanic, we find several ethnic groups that made up the aboriginal culture: Tainos, Igneris, Ciboneyes, Kalinago and Guanahatabeyes.

Asteromorphs: figures of celestial stars[10] By the mid-16th century, Spanish colonization had brought a brutal end to the Taíno civilization, having wiped out between 80 and 90% of the indigenous population through genocide and foreign-brought diseases.

[11] Warfare, the encomienda system, and no resistance to Old World epidemic outbreaks, like smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus decimated the Taíno population on the island, the first indigenous victims of Spanish colonization of the Americas.

[12] Over time, the mestizo children of the Spanish colonizers and Taíno concubines intermarried with West Africans after their arrival from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, creating the tri-racial Creole culture found in the country today.

[13] According to the Marquis of Lozoya, there were three capital works during the 16th century in the colony; these include a mural painting representing a martyred saint held in the Treasury Room of the Catedral Primada; the magnificent copy of the Virgen de la Antigua, found in a chapel of the same Cathedral; and La Virgen de Cristóbal Colón, believed to be the oldest preserved portrait of Columbus and though painted in Santo Domingo, today it remains on display in Lázaro Galdiano Museum.

It was saved from a shipwreck in the vicinity of the Virgin Islands when it was brought by ship to Santo Domingo and considered the first large-format painting to arrive to the Americas, measuring at 2.85 meters in height by 1.75 wide.

Considered the oldest preserved painting of the colony, it was brought to the island by two brothers, Alonso and Antonio de Trejo, from their home in Placencia, in the region of Extremadura in 1502.

According to traditional legend, the Virgin de la Altagracia appeared beneath an orange tree in the town of Higüey, inspiring invocations and turning her into a national icon of the island.

[13] Overall, the Hispanic, Catholic and stately aesthetic, including a medieval-renaissance eclecticism, reflects the art of the period, and is above all expressed in the civil and religious architecture of Santo Domingo created during this time.

The repressive six-year period of the government of Buenaventura Báez ended; the threat of annexation to the United States disappeared after the bill is rejected in the Senate and repudiated by the Dominican people; and in the beginning of 1874, a Constituent Assembly is called to reform the fundamental Charter of the country.

A flourishing of the arts, letters, and overall educational and societal reform develop after the founding of various teaching centers and civic societies that promote the creation of artistic and literary works.

[21] A whole generation of artists sprouted as Puerto Rican social theorist, Eugenio Maria de Hostos's influence on educational, intellectual, and moral issues proliferated throughout the Antilles.

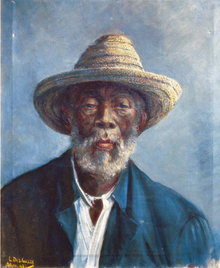

[23] During his three-year stay, he came to teach at the Dominican capital, teaching a group of future artists who met there and became interconnected, including Abelardo Rodríguez Urdaneta, Arturo Grullón, Luis Desangles, Leopoldo Navarro, Américo Lugo, Máximo Grullón, Arquímedes de la Concha, Ángel Perdomo, Adolfo García Obregón, Alfredo Senior, Ramón Mella Ligthgow, Adriana Billini, among others.

[25] Press articles fighting the dictatorship circulated in the capital city during the last decade of the nineteenth century, inspiring some students of Desangles to conceive of making several paintings in which the image of the dictator appeared dead by hanging.

One morning on the early days of February 1893 in Colón Park, at the foot of the colonizer's statue, a painting of President Heureaux hanging from a tree with his tongue sticking out was found.

The impact that the Republicans caused in the capital city was expressed in various ways, starting with the alteration of nightlife since the Spanish were used to everything at later hours; they founded cinemas, multiplied cafes, and established restaurants.

[31] In addition to nighttime recreation, the exiles also favorably influenced intellectual and university development, since many of them were academics, writers, and artists of various manifestations: musicians, theater players, sculptors, painters and craftsmen.

[31] The artists who resided in Santo Domingo during this time included: Josep Gausachs, Manolo Pascual, Juan Bautista Acher, Saul Steimberg, Kurt Schnitzer, George Hausdorf, José Vela Zanetti, Francisco Vásquez Díaz, Antonio Bernad Gonzálvez, Ernesto Lothar, Josep Rovira, Francisco Dorado, Mounia André, Joaquín de Alba, Hans Pape, Ana María Schwartz, Alejandro Solana Ferrer, and many others.

[32] The legacy these Spanish and Central European refugees have on Dominican art is especially evident in the approach to avant-garde languages like surrealism and abstraction seen in the works of native artists in the later half of the 20th century.

[33] Painters from the 1950–1990 generation with impressionist tendencies are: Mario Grullón, Marianela Jiménez, Xavier Amiama, Nidia Serra, Jacinto Domínguez, Pluntarco Andújar, Rafi Vásquez, among others.

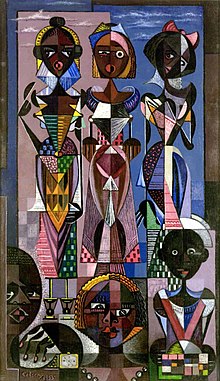

The cubist tendency that developed in Dominican art is that of the black Antillean world, "the intimate drama of the tormented life of man and through the music that elevates him from his religious rites", wrote Colson.

Colonial cubism can also be appreciated as a Dominican, Caribbean and even Antillean style, since its aesthetic is assumed in several countries like Haiti, Puerto Rico, and other islands as a result of Colson's influence.

The three parallels drawn by these languages converge in the eclectic abstract expressionist that three important painters assume in Dominican painting: Eligio Pichardo, Guillo Pérez and Paul Giudicelli.

Other important artists that produced abstract works are Gilberto Hernandez Ortega, Dario Suro, Jacinto Dominguez, Ada Balcear, Tito Canepa, Silvano Lora, Elsa Núñez, and Delia Weber, Fernando Peña Defilló, Norbeto Santana, Jose Perdomo, Clara Ledema, Dionisio Pichardo, and Luichy Martínez Richiez.

His characteristics involve a focus on fleeting and virtual aspects of waking life, associating many elements of nature (flowers, fruits, birds, ...) in dreamlike visions suggestive of fantasy and memory.

Surrealism in the Dominican Republic had even more strong supporters who created unique works including Jaime Colson, Ivan Tovar, Gilberto Hernández Ortega, Luis Oscar Romero, and Jose Felix Moya.

The eighties are the only generation of artists that formed a militant cohesion, defined not as members in a group, but as a collective spirit, where the magical and surreal seems to assert itself with much greater emphasis than the expressionist.

Their heads or leaders are: Gabino Rosario, Hamlet Rubio, Germán Olivares, Persio Checo, José Ramón Medina, Genaro Phillips, Hilario Olivo, Jorge Pineda, Belkis Ramírez, Tony Capellan, Gabino Rosario, Octavio Paniagua, Elvis Aviles, Luz Severino, Carlos Hinojosa, Dionisio Plubio de la Paz, Magdeleno Portorreal, to name a few.