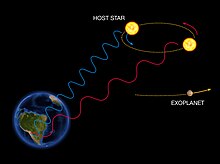

Doppler spectroscopy

However, the technology of the time produced radial-velocity measurements with errors of 1,000 m/s or more, making them useless for the detection of orbiting planets.

[4][5] Advances in spectrometer technology and observational techniques in the 1980s and 1990s produced instruments capable of detecting the first of many new extrasolar planets.

[6] Using this instrument, astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz identified 51 Pegasi b, a "Hot Jupiter" in the constellation Pegasus.

The HARPS spectrograph, installed at the La Silla Observatory in Chile in 2003, can identify radial-velocity shifts as small as 0.3 m/s, enough to locate many possibly rocky, Earth-like planets.

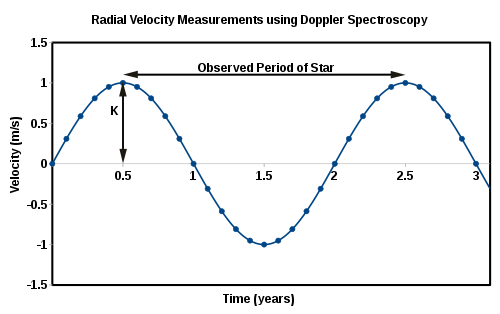

Using mathematical best-fit techniques, astronomers can isolate the tell-tale periodic sine wave that indicates a planet in orbit.

The Bayesian Kepler periodogram is a mathematical algorithm, used to detect single or multiple extrasolar planets from successive radial-velocity measurements of the star they are orbiting.

It involves a Bayesian statistical analysis of the radial-velocity data, using a prior probability distribution over the space determined by one or more sets of Keplerian orbital parameters.

The method has been applied to the HD 208487 system, resulting in an apparent detection of a second planet with a period of approximately 1000 days.

However, this planet was not found in re-reduced data,[14][15] suggesting that this detection was an artifact of the Earth's orbital motion around the Sun.

The first non-transiting planet to have its mass found this way was Tau Boötis b in 2012 when carbon monoxide was detected in the infrared part of the spectrum.

Observations of a real star would produce a similar graph, although eccentricity in the orbit will distort the curve and complicate the calculations below.

If the orbital plane of the planet happens to line up with the line-of-sight of the observer, then the measured variation in the star's radial velocity is the true value.

To correct for this effect, and so determine the true mass of an extrasolar planet, radial-velocity measurements can be combined with astrometric observations, which track the movement of the star across the plane of the sky, perpendicular to the line-of-sight.