Exoplanet

[1][2] In collaboration with ground-based and other space-based observatories the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is expected to give more insight into exoplanet traits, such as their composition, environmental conditions, and potential for life.

However, the study of planetary habitability also considers a wide range of other factors in determining the suitability of a planet for hosting life.

[18][19] The official definition of the term planet used by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) only covers the Solar System and thus does not apply to exoplanets.

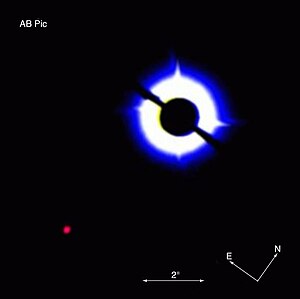

Most directly imaged planets as of April 2014 are massive and have wide orbits so probably represent the low-mass end of a brown dwarf formation.

[34] The Exoplanet Data Explorer includes objects up to 24 Jupiter masses with the advisory: "The 13 Jupiter-mass distinction by the IAU Working Group is physically unmotivated for planets with rocky cores, and observationally problematic due to the sin i ambiguity.

[47] In 1952, more than 40 years before the first hot Jupiter was discovered, Otto Struve wrote that there is no compelling reason that planets could not be much closer to their parent star than is the case in the Solar System, and proposed that Doppler spectroscopy and the transit method could detect super-Jupiters in short orbits.

In 1855, William Stephen Jacob at the East India Company's Madras Observatory reported that orbital anomalies made it "highly probable" that there was a "planetary body" in this system.

[51] During the 1950s and 1960s, Peter van de Kamp of Swarthmore College made another prominent series of detection claims, this time for planets orbiting Barnard's Star.

In 1990, additional observations were published that supported the existence of the planet orbiting Gamma Cephei,[58] but subsequent work in 1992 again raised serious doubts.

[60] On 9 January 1992, radio astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of two planets orbiting the pulsar PSR 1257+12.

[62] In the early 1990s, a group of astronomers led by Donald Backer, who were studying what they thought was a binary pulsar (PSR B1620−26 b), determined that a third object was needed to explain the observed Doppler shifts.

Within a few years, the gravitational effects of the planet on the orbit of the pulsar and white dwarf had been measured, giving an estimate of the mass of the third object that was too small for it to be a star.

Astronomers were surprised by these "hot Jupiters", because theories of planetary formation had indicated that giant planets should only form at large distances from stars.

[76] As of January 2020, NASA's Kepler and TESS missions had identified 4374 planetary candidates yet to be confirmed,[77] several of them being nearly Earth-sized and located in the habitable zone, some around Sun-like stars.

[78][79][80] In September 2020, astronomers reported evidence, for the first time, of an extragalactic planet, M51-ULS-1b, detected by eclipsing a bright X-ray source (XRS), in the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51a).

[124][125][126] For gas giants, geometric albedo generally decreases with increasing metallicity or atmospheric temperature unless there are clouds to modify this effect.

Optical albedo decreases with increasing mass, because higher-mass giant planets have higher surface gravities, which produces lower cloud-column depths.

[133] Earth's magnetic field results from its flowing liquid metallic core, but on massive super-Earths with high pressure, different compounds may form which do not match those created under terrestrial conditions.

Compounds may form with greater viscosities and high melting temperatures, which could prevent the interiors from separating into different layers and so result in undifferentiated coreless mantles.

The more magnetically active a star is, the greater the stellar wind and the larger the electric current leading to more heating and expansion of the planet.

[137][138] Although scientists previously announced that the magnetic fields of close-in exoplanets may cause increased stellar flares and starspots on their host stars, in 2019 this claim was demonstrated to be false in the HD 189733 system.

The failure to detect "star-planet interactions" in the well-studied HD 189733 system calls other related claims of the effect into question.

Kepler-1520b is a small rocky planet, very close to its star, that is evaporating and leaving a trailing tail of cloud and dust like a comet.

[178] Tidally locked planets in a 1:1 spin-orbit resonance would have their star always shining directly overhead on one spot, which would be hot with the opposite hemisphere receiving no light and being freezing cold.

[186] Furthermore, a potentially habitable planet must orbit a stable star at a distance within which planetary-mass objects with sufficient atmospheric pressure can support liquid water at their surfaces.

[197][198] Habitable zones have usually been defined in terms of surface temperature, however over half of Earth's biomass is from subsurface microbes,[199] and the temperature increases with depth, so the subsurface can be conducive for microbial life when the surface is frozen and if this is considered, the habitable zone extends much further from the star,[200] even rogue planets could have liquid water at sufficient depths underground.

[201] In an earlier era of the universe the temperature of the cosmic microwave background would have allowed any rocky planets that existed to have liquid water on their surface regardless of their distance from a star.

[209] Eccentric planets further out than the habitable zone would still have frozen surfaces, but the tidal heating could create a subsurface ocean similar to Europa's.

Of these, Kepler-186f is in similar size to Earth with its 1.2-Earth-radius measure, and it is located towards the outer edge of the habitable zone around its red dwarf star.

[218] One proposed explanation is that hot Jupiters tend to form in dense clusters, where perturbations are more common and gravitational capture of planets by neighboring stars is possible.