Double bass

Classical players perform both bowed and pizz notes using vibrato, an effect created by rocking or quivering the left hand finger that is contacting the string, which then transfers an undulation in pitch to the tone.

In general, very loud, low-register passages are played with little or no vibrato, as the main goal with low pitches is to provide a clear fundamental bass for the string section.

Jazz and rockabilly bassists develop virtuoso pizzicato techniques that enable them to play rapid solos that incorporate fast-moving triplet and sixteenth note figures.

The double bass player stands, or sits on a high stool, and leans the instrument against their body, turned slightly inward to put the strings comfortably in reach.

The double bass also differs from members of the violin family in that the shoulders are typically sloped and the back is often angled (both to allow easier access to the instrument, particularly in the upper range).

While this development makes fine tuners on the tailpiece (important for violin, viola and cello players, as their instruments use friction pegs for major pitch adjustments) unnecessary, a very small number of bassists use them nevertheless.

), are very resistant to humidity and heat, as well to the physical abuse they are apt to encounter in a school environment (or, for blues and folk musicians, to the hazards of touring and performing in bars).

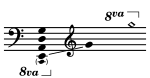

The upper limit of this range is extended a great deal for 20th- and 21st-century orchestral parts (e.g., Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kijé Suite (c.1933) bass solo, which calls for notes as high as D4 and E♭4).

Now, it is unusual for a player to be equally proficient in both positions, so some soloists sit (as with Joel Quarrington, Jeff Bradetich, Thierry Barbé, and others) and some orchestral bassists stand.

While playing in thumb position, few players use the fourth (little) finger, as it is usually too weak to produce reliable tone (this is also true for cellists), although some extreme chords or extended techniques, especially in contemporary music, may require its use.

[32] The popularity of the instrument is documented in Leopold Mozart's second edition of his Violinschule, where he writes "One can bring forth difficult passages easier with the five-string violone, and I heard unusually beautiful performances of concertos, trios, solos, etc."

The leading double bassists from the mid-to-late 18th century, such as Josef Kämpfer, Friedrich Pischelberger, and Johannes Mathias Sperger employed the "Viennese" tuning.

During the same time, a prominent school of bass players in the Czech region arose, which included Franz Simandl, Theodore Albin Findeisen, Josef Hrabe, Ludwig Manoly, and Adolf Mišek.

From the 1960s through the end of the century Gary Karr was the leading proponent of the double bass as a solo instrument and was active in commissioning or having hundreds of new works and concerti written especially for him.

In 1977 Dutch-Hungarian composer Géza Frid wrote a set of variations on The Elephant from Saint-Saëns' Le Carnaval des Animaux for scordatura double bass and string orchestra.

Later composers who wrote chamber works for this quintet include Ralph Vaughan Williams, Colin Matthews, Jon Deak, Frank Proto, and John Woolrich.

Rossini and Dragonetti composed duos for cello and double bass, as did Johannes Matthias Sperger, a major soloist on the "Viennese" tuning instrument of the 18th century.

"The Elephant" from Camille Saint-Saëns' The Carnival of the Animals is a satirical portrait of the double bass, and American virtuoso Gary Karr made his televised debut playing "The Swan" (originally written for the cello) with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

The third movement of Gustav Mahler's first symphony features a solo for the double bass that quotes the children's song Frere Jacques, transposed into a minor key.

Compositions for four double basses exist by Gunther Schuller, Jacob Druckman, James Tenney, Claus Kühnl, Robert Ceely, Jan Alm, Bernhard Alt, Norman Ludwin, Frank Proto, Joseph Lauber, Erich Hartmann, Colin Brumby, Miloslav Gajdos and Theodore Albin Findeisen.

Paul Chambers (who worked with Miles Davis on the famous Kind of Blue album) achieved renown for being one of the first jazz bassists to play bebop solos with the bow.

An early bluegrass bassist to rise to prominence was Howard Watts (also known as Cedric Rainwater), who played with Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys beginning in 1944.

[57] The upright bass remained an integral part of pop lineups throughout the 1950s, as the new genre of rock and roll was built largely upon the model of rhythm and blues, with strong elements also derived from jazz, country, and bluegrass.

Shannon Birchall, of the Australian folk-rock group the John Butler Trio,[61] makes extensive use of upright basses, performing extended live solos in songs such as Betterman.

This is a vigorous version of pizzicato where the strings are "slapped" against the fingerboard between the main notes of the bass line, producing a snare drum-like percussive sound.

Free jazz and post-bop bassist Charlie Haden (1937–2014) is best known for his long association with saxophonist Ornette Coleman, and for his role in the 1970s-era Liberation Music Orchestra, an experimental group.

Eddie Gómez and George Mraz, who played with Bill Evans and Oscar Peterson, respectively, and are both acknowledged to have furthered expectations of pizzicato fluency and melodic phrasing.

Conservatories, which are the standard musical training system in France and in Quebec (Canada) provide lessons and amateur orchestral experience for double bass players.

In some cases, blues or rockabilly bassists may have obtained some initial training through the classical or jazz pedagogy systems (e.g., youth orchestra or high school big band).

A person auditioning for a role as a bassist in some styles of pop or rock music may be expected to demonstrate the ability to perform harmony vocals as a backup singer.