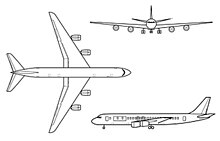

Douglas DC-8

After losing the USAF's tanker competition to the rival Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker in May 1954, Douglas announced in June 1955 its derived jetliner project marketed to civil operators.

Following Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification in August 1959, the DC-8 entered service with Delta Air Lines on September 18.

[3][4] Initially, it appeared to be a success, but the Comet was grounded in 1954 after two fatal accidents which were subsequently attributed to rapid metal fatigue failure of the pressure cabin.

[5] Various aircraft manufacturers benefited from the findings and experiences gained from the investigation into Comet losses; specifically, Douglas paid significant attention to detail in the design of the DC-8's pressurized cabin.

[8] The Comet disasters, and the airlines' subsequent lack of interest in jets, seemed to validate the company's decision to remain with propeller-driven aircraft, but its inaction enabled rival manufacturers to take the lead instead.

The company also supplied the SAC's refueling aircraft, the piston-engined KC-97 Stratofreighters, but these proved to be too slow and low flying to easily work with the new jet bombers.

[11] Believing that a requirement for a jet-powered tanker was a certainty, Boeing started work on a new jet aircraft for this role that could be adapted into an airliner.

[8] By mid-1953, the team had settled on a form similar to the final DC-8; an 80-seat, low-wing aircraft powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT3C turbojet engines, 30° wing sweep, and an internal cabin diameter of 11 feet (3.35 m) to allow five-abreast seating.

In May 1954, the USAF circulated its requirement for 800 jet tankers to Boeing, Douglas, Convair, Fairchild Aircraft, Lockheed Corporation, and Martin Marietta.

[15][14] Donald Douglas was reportedly shocked by the rapidity of the decision which, he claimed, had been made before the competing companies even had time to complete their bids.

[17] Four versions were offered to begin with, all with the same 150-foot-6-inch (45.87 m) long airframe with a 141-foot-1-inch (43.00 m) wingspan, but varying in engines and fuel capacity, and with maximum weights of about 240,000–260,000 lb (109–118 metric tons).

[citation needed] Douglas' previous thinking about the airliner market seemed to be coming true; the transition to turbine power looked likely to be to turboprops rather than turbojets.

The pioneering 40–60-seat Vickers Viscount was in service and proving popular with passengers and airlines: it was faster, quieter, and more comfortable than piston-engined types.

[20] Meanwhile, the Comet remained grounded, the French 90-passenger twin jet Sud Aviation Caravelle prototype had just flown for the first time, and the Boeing 707 was not expected to be available until late 1958.

[citation needed] There the matter rested until October 1955, when Pan American World Airways placed simultaneous orders with Boeing for 20 707s and Douglas for 25 DC-8s.

In 1956, Air India, BOAC, Lufthansa, Qantas, and TWA added over 50 to the 707 order book, while Douglas sold 22 DC-8s to Delta, Swissair, TAI, Trans Canada, and UAT.

Following complaints by neighboring residents, the city refused, so Douglas moved its airliner production line to Long Beach Airport.

[17] The first DC-8 N8008D was rolled out of the new Long Beach factory on 9 April 1958 and flew for the first time, in Series 10 form, on 30 May for two hours and seven minutes with the crew being led by A.G.

Douglas made a massive effort to close the gap with Boeing, using no fewer than ten aircraft for flight testing to achieve Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification for the first of the many DC-8 variants in August 1959.

[26] Several modifications proved to be necessary: the original air brakes on the lower rear fuselage were found to be ineffective and were deleted as engine thrust reversers had become available; unique leading-edge slots were added to improve low-speed lift; the prototype was 25 kn (46 km/h) short of its promised cruising speed and a new, slightly larger wingtip had to be developed to reduce drag.

The aircraft, crewed by Captain William Magruder, First Officer Paul Patten, Flight Engineer Joseph Tomich and Flight Test Engineer Richard Edwards, took off from Edwards Air Force Base in California and was accompanied to altitude by a F-104 Starfighter supersonic chase aircraft flown by Chuck Yeager.

[citation needed] Douglas' refusal to offer different fuselage sizes made it less adaptable and compelled airlines such as Delta and United to look elsewhere for short to medium range types.

Increasing traffic densities and changing public attitudes led to complaints about aircraft noise and moves to introduce restrictions.

While third parties had developed aftermarket hushkits, there was initially no meaningful action taken by Douglas to fulfil these requests and effectively enable the DC-8 to remain in service.

[40] The Super Seventies proved to be a great success, being roughly 70% quieter than the 60 Series and, at the time of their introduction, the world's quietest four-engined airliner.

[44] Higher-powered 15,800 lb (70.8 kN) thrust Pratt & Whitney JT4A-3 turbojets[44] (without water injection) allowed a weight increase to 276,000 pounds (125,190 kg).

[44] For intercontinental routes, the three Series 30 variants combined JT4A engines with a one-third increase in fuel capacity and strengthened fuselage and landing gear.

The DC-8-33 of November 1960 substituted 17,500 lb (78.4 kN) JT4A-11 turbojets, a modification to the flap linkage to allow a 1.5° setting for more efficient cruise, stronger landing gear, and 315,000-pound (142,880 kg) maximum weight.

The Conway was an improvement over the turbojets that preceded it, but the Series 40 sold poorly because of the traditional reluctance of U.S. airlines to buy a foreign product and because the still-more-advanced Pratt & Whitney JT3D turbofan was due in early 1961.

[44] The DC-8-71, DC-8-72, and DC-8-73 were straightforward conversions of the -61, -62 and -63 primarily involving the replacement of the JT3D engines with the more fuel-efficient CFM International CFM56-2, a high bypass turbofan, which produced 22,000 lbf (98.5 kN) of thrust.