Ray Bradbury

The New York Times called Bradbury "An author whose fanciful imagination, poetic prose, and mature understanding of human character have won him an international reputation" and "the writer most responsible for bringing modern science fiction into the literary mainstream".

I sat below, in the front row, and he reached down with a flaming sword full of electricity and he tapped me on both shoulders and then the tip of my nose and he cried, "Live, forever!"

"[20] Bradbury admitted that he stopped reading science-fiction books in his 20s and embraced a broad field of literature that included poets Alexander Pope and John Donne.

He recounted seeing Cary Grant, Marlene Dietrich and Mae West, who, he learned, made a regular appearance every Friday night, bodyguard in tow.

[21] Bradbury was free to start a career in writing when, owing to his bad eyesight, he was rejected for induction into the military during World War II.

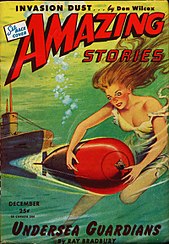

[21] His first collection of short stories, Dark Carnival, was published in 1947 by Arkham House, a small press in Sauk City, Wisconsin, owned by August Derleth.

Reviewing Dark Carnival for the New York Herald Tribune, Will Cuppy proclaimed Bradbury "suitable for general consumption" and predicted that he would become a writer of the caliber of British fantasist John Collier.

[26] After a rejection notice from the pulp Weird Tales, Bradbury submitted "Homecoming" to Mademoiselle, where it was spotted by a young editorial assistant named Truman Capote.

In UCLA's Powell Library, in a study room with typewriters for rent for ten cents per half-hour., Bradbury wrote his classic story of a book burning future, Fahrenheit 451, which was about 50,000 words long, costing $9.80 from the typewriter-rental fees.

A chance encounter in a Los Angeles bookstore with British expatriate writer Christopher Isherwood gave Bradbury the opportunity to put The Martian Chronicles into the hands of a respected critic.

[33] Bradbury claimed a wide variety of influences, and described discussions he might have had with his favorite writers, among them Robert Frost, William Shakespeare, John Steinbeck, Aldous Huxley, and Thomas Wolfe.

He graduated from Los Angeles High School, where he took poetry classes with Snow Longley Housh and short-story writing courses taught by Jeannet Johnson.

In Green Town, Bradbury's favorite uncle sprouts wings, traveling carnivals conceal supernatural powers, and his grandparents provide room and board to Charles Dickens.

There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap opera cries, sleep walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there.

During his introductory comments and on-air banter with Marx, Bradbury briefly discussed some of his books and other works, including giving an overview of "The Veldt", his short story published six years earlier in The Saturday Evening Post under the title "The World the Children Made".

[51] Bradbury was a consultant for the United States Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair and wrote the narration script for The American Journey attraction there.

Initially, the writers plagiarized his stories, but a diplomatic letter from Bradbury led to the company's paying him and negotiating properly licensed adaptations of his work.

[63] Bradbury is featured prominently in two documentaries related to his classic 1950s–1960s era: Jason V Brock's Charles Beaumont: The Life of Twilight Zone's Magic Man,[64] detailing his troubles with Rod Serling and his friendships with writers Charles Beaumont, George Clayton Johnson, and most especially his dear friend William F. Nolan; and Brock's The AckerMonster Chronicles!, which delves into the life of former Bradbury agent, close friend, mega-fan and Famous Monsters of Filmland editor Forrest J Ackerman.

[72] In October 2001, Bradbury published all the Family stories he had written in one book with a connecting narrative, From the Dust Returned, featuring a wraparound Addams cover of the original "Homecoming" illustration.

And, swearing, they left, leaving me alone with Bondarchuk ...[76]Late in life, Bradbury retained his dedication and passion despite the "devastation of illnesses and deaths of many good friends".

They remained close for nearly 30 years, after Roddenberry asked him to write for Star Trek; Bradbury declined, claiming that he "never had the ability to adapt other people's ideas into any sensible form".

[79] Bradbury chose a burial place at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles, with a headstone that reads "Author of Fahrenheit 451".

[88] The Los Angeles Times credited him with the ability "to write lyrically and evocatively of lands an imagination away, worlds he anchored in the here and now with a sense of visual clarity and small-town familiarity".

[69] The Washington Post noted several modern-day technologies that Bradbury had envisioned much earlier, such as the idea of banking ATMs and earbuds and Bluetooth headsets in Fahrenheit 451, and the concepts of artificial intelligence in I Sing the Body Electric.

[citation needed] In the winter of 1955–56, after a consultation with his Doubleday editor, Bradbury deferred publication of a novel based on Green Town, the pseudonym for his hometown.

[98] From 1950 to 1954, 31 of Bradbury's stories were adapted by Al Feldstein for EC Comics (seven of them uncredited in six stories, including "Kaleidoscope" and "Rocket Man" being combined as "Home To Stay"—for which Bradbury was retroactively paid—and EC's first version of "The Handler" under the title "A Strange Undertaking") and 16 of these were collected in the paperbacks, The Autumn People (1965) and Tomorrow Midnight (1966), both published by Ballantine Books with cover illustrations by Frank Frazetta.

"The Merry-Go-Round", a half-hour film adaptation of Bradbury's "The Black Ferris", praised by Variety, was shown on Starlight Summer Theater in 1954 and NBC's Sneak Preview in 1956.

Bradbury was hired in 1953 by director John Huston to work on the screenplay for his film version of Melville's Moby Dick (1956), which stars Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab, Richard Basehart as Ishmael, and Orson Welles as Father Mapple.

The original cast for this production featured Booth Coleman, Joby Baker, Fredric Villani, Arnold Lessing, Eddie Sallia, Keith Taylor, Richard Bull, Gene Otis Shane, Henry T. Delgado, F. Murray Abraham, Anne Loos, and Len Lesser.

[110] In 1993, "The Smile" has been adapted as Viktor Chaika's music video "Mona Lisa" which included footage from Soviet TV series This Fantastic World.