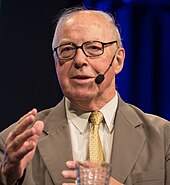

David Kelly (weapons expert)

A former head of the Defence Microbiology Division working at Porton Down, Kelly was part of a joint US-UK team that inspected civilian biotechnology facilities in Russia in the early 1990s and concluded they were running a covert and illegal BW programme.

He was appointed to the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) in 1991 as one of its chief weapons inspectors in Iraq and led ten of the organisation's missions between May 1991 and December 1998.

He also worked with UNSCOM's successor, the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and led several of their missions into Iraq.

[15][e] The department had only a small number of microbiologists when he arrived, and most of their work involved the decontamination of Gruinard Island, which had been used during the Second World War for experiments with weaponised anthrax.

[16] In 1989 Vladimir Pasechnik, the senior Soviet biologist and bioweapons developer, defected to the UK and provided intelligence about the clandestine biological warfare (BW) programme, Biopreparat.

Skirmishes occurred over access to an explosive aerosol chamber because the officials knew that closer examination would reveal damning evidence of offensive BW activities.

The officials were unable to properly account for the presence of smallpox and for the research being undertaken in a dynamic aerosol test chamber on orthopoxvirus, which was capable of explosive dispersal.

At the Institute of Ultrapure Preparations in Leningrad (Pasechnik's former workplace), dynamic and explosive test chambers were passed off as being for agricultural projects, contained milling machines were described as being for the grinding of salt, and studies on plague, especially production of the agent, were misrepresented.

[29] He went on to add that "Russia's refusal to provide a complete account of its past and current BW activity and the inability of the American–British teams to gain access to Soviet/Russian military industrial facilities were significant contributory factors".

[15][31] The Iraqis had provided Rolf Ekéus, the director of UNSCOM, with a list of sites connected with the research and production of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in the country, about half of which had been bombed during Operation Desert Storm.

[3][39] During an inspection mission to Iraq in 1998, Kelly worked alongside an American translator and US Air Force officer, Mai Pederson, who introduced him to the Baháʼí Faith.

He included information on mobile weapons laboratories, which he described as "trucks and train cars ... easily moved and ... designed to evade detection by inspectors.

[69][70] On 22 May 2003 Kelly met Andrew Gilligan, the Defence and Diplomatic Correspondent for BBC Radio 4's Today programme, at the Charing Cross Hotel, London.

[87] Their conversation also included the possible involvement of Campbell in the inclusion of the 45-minute claim in the dossier: SW OK just back momentarily on the 45 minute issue I'm feeling like I ought to just explore that a little bit more with you the um err.

[88]Despite the denial from the government, on 1 June—the day after Kelly and Watts had spoken on the telephone—Gilligan wrote an article for The Mail on Sunday in which he specifically named Campbell; it was titled: "I asked my intelligence source why Blair misled us all over Saddam's weapons.

[89] According to the journalist Miles Goslett, the report on the Today programme "caused little more than a ripple" of interest;[90] the newspaper article "was of major international significance.

[91] As political tumult between Downing Street and the BBC developed,[92][93] Kelly alerted his line manager at the MoD, Bryan Wells, that he had met Gilligan and discussed, among other points, the 45-minute claim.

Kelly said of Gilligan's evidence that "The description of that meeting in small part matches my interaction with him especially my personal evaluation of Iraq's capability but the overall character is quite different".

[106] According to Mrs Kelly, the couple left the house within 15 minutes and drove to Cornwall, breaking the journey overnight in Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, where they arrived by 9:45 pm.

[111] While in Cornwall, on the morning of 11 July, Kelly had a telephone call from Bryan Wells to tell him that he would have to appear in front of the Intelligence and Security and Foreign Affairs select committees.

He spoke so softly the fans in the room were turned off so the committee members could hear him reply; according to Baker, "Every word [from Kelly] was weighed carefully and some painful circumlocutions resulted".

[128] He had received several emails from well-wishers, including from The New York Times journalist Judith Miller, to which he replied "I will wait until the end of the week before judging—many dark actors playing games.

Mangold states that "[the] most likely explanation is that he learned from a well-meaning friend at the Ministry of Defence that the BBC had tape-recorded evidence which, when published, would show that he had indeed said the things to Susan Watts that he had formally denied saying".

It appears he ingested up to 29 tablets of co-proxamol, an analgesic drug; he also cut his left wrist with a pruning knife he had owned since his youth, severing his ulnar artery.

The second stage of the inquiry took place between 15 and 25 September 2003; Hutton explained that he "would ask persons, who had already given evidence and whose conduct might possibly be the subject of criticism in my report, to come back to be examined further".

[169] Hutton reported on 28 January 2004 and wrote "I am satisfied that Dr Kelly took his own life by cutting his left wrist and that his death was hastened by his taking Co-proxamol tablets.

The pathologist wrote in the post-mortem: It is my opinion that the main factor involved in bringing about the death of David Kelly is the bleeding from the incised wounds to his left wrist.

Furthermore, on the balance of probabilities, it is likely that the ingestion of an excess number of co-proxamol tablets coupled with apparently clinically silent coronary artery disease would both have played a part in bringing about death more certainly and more rapidly than would have otherwise been the case.

[195][196] Kelly was the subject of a 2005 television drama, The Government Inspector, starring Mark Rylance,[197][198] and "Justifying War: Scenes from the Hutton Inquiry" a radio play by the Tricycle Theatre.

He has pursued this work tirelessly and with good humour despite the significant hardship, hostility and personal risk encountered during extended periods of service in both countries. ...

–

Southmoor

, where he lived

–

Southmoor

, where he lived

– Harrowdown Hill, where his body was found.

– Harrowdown Hill, where his body was found.

Both locations are in Oxfordshire . [ 126 ]