Dr. Seuss

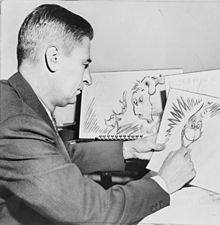

Theodor Seuss Geisel (/suːs ˈɡaɪzəl, zɔɪs -/ ⓘ sooss GHY-zəl, zoyss -;[2][3][4] March 2, 1904 – September 24, 1991)[5] was an American children's author and cartoonist.

He also worked as an illustrator for advertising campaigns, including for FLIT and Standard Oil, and as a political cartoonist for the New York newspaper PM.

During World War II, he took a brief hiatus from children's literature to illustrate political cartoons, and he worked in the animation and film department of the United States Army.

[20][21] At Oxford, he met his future wife Helen Palmer, who encouraged him to give up becoming an English teacher in favor of pursuing drawing as a career.

"[20] Geisel left Oxford without earning a degree and returned to the United States in February 1927,[22] where he immediately began submitting writings and drawings to magazines, book publishers, and advertising agencies.

[24] Later that year, Geisel accepted a job as writer and illustrator at the humor magazine Judge, and he felt financially stable enough to marry Palmer.

[26] In early 1928, one of Geisel's cartoons for Judge mentioned Flit, a common bug spray at the time manufactured by Standard Oil of New Jersey.

As Geisel gained fame for the Flit campaign, his work was in demand and began to appear regularly in magazines such as Life, Liberty and Vanity Fair.

[33] In 1936, Geisel and his wife were returning from an ocean voyage to Europe when the rhythm of the ship's engines inspired the poem that became his first children's book: And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

As World War II began, Geisel turned to political cartoons, drawing over 400 in two years as editorial cartoonist for the left-leaning New York City daily newspaper, PM.

[41][42] His cartoons were strongly supportive of President Roosevelt's handling of the war, combining the usual exhortations to ration and contribute to the war effort with frequent attacks on Congress[43] (especially the Republican Party),[44] parts of the press (such as the New York Daily News, Chicago Tribune and Washington Times-Herald),[45] and others for criticism of Roosevelt, criticism of aid to the Soviet Union,[46][47] investigation of suspected Communists,[48] and other offences that he depicted as leading to disunity and helping the Nazis, intentionally or inadvertently.

[51] After the war, Geisel and his wife moved to the La Jolla community of San Diego, California,[52][53] where he returned to writing children's books.

William Ellsworth Spaulding was the director of the education division at Houghton Mifflin (he later became its chairman), and he compiled a list of 348 words that he felt were important for first-graders to recognize.

It retained the drawing style, verse rhythms, and all the imaginative power of Geisel's earlier works but, because of its simplified vocabulary, it could be read by beginning readers.

The Cat in the Hat and subsequent books written for young children achieved significant international success and they remain very popular today.

In 1955, Dartmouth awarded Geisel an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters, with the citation: Creator and fancier of fanciful beasts, your affinity for flying elephants and man-eating mosquitoes makes us rejoice you were not around to be Director of Admissions on Mr. Noah's ark.

But our rejoicing in your career is far more positive: as author and artist you singlehandedly have stood as St. George between a generation of exhausted parents and the demon dragon of unexhausted children on a rainy day.

There was an inimitable wriggle in your work long before you became a producer of motion pictures and animated cartoons and, as always with the best of humor, behind the fun there has been intelligence, kindness, and a feel for humankind.

An Academy Award winner and holder of the Legion of Merit for war film work, you have stood these many years in the academic shadow of your learned friend Dr. Seuss; and because we are sure the time has come when the good doctor would want you to walk by his side as a full equal and because your College delights to acknowledge the distinction of a loyal son, Dartmouth confers on you her Doctorate of Humane Letters.

[63][non-primary source needed] He won a special Pulitzer Prize in 1984 citing his "contribution over nearly half a century to the education and enjoyment of America's children and their parents".

[64][non-primary source needed] Geisel died of cancer on September 24, 1991, at his home in the La Jolla community of San Diego at the age of 87.

[citation needed] In 2004, U.S. children's librarians established the annual Theodor Seuss Geisel Award to recognize "the most distinguished American book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding year".

[80] His cartoons portrayed the fear of communism as overstated, finding greater threats in the House Committee on Unamerican Activities and those who threatened to cut the U.S.'s "life line"[47] to the USSR and Stalin, whom he once depicted as a porter carrying "our war load".

[83][84] Geisel converted a copy of one of his famous children's books, Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now!, into a polemic shortly before the end of the 1972–1974 Watergate scandal, in which U.S. president Richard Nixon resigned, by replacing the name of the main character everywhere that it occurred.

Geisel and later his widow Audrey objected to this use; according to her attorney, "She doesn't like people to hijack Dr. Seuss characters or material to front their own points of view.

[95][96] Geisel's early artwork often employed the shaded texture of pencil drawings or watercolors, but in his children's books of the postwar period, he generally made use of a starker medium—pen and ink—normally using just black, white, and one or two colors.

Geisel evidently enjoyed drawing architecturally elaborate objects, and a number of his motifs are identifiable with structures in his childhood home of Springfield, including examples such as the onion domes of its Main Street and his family's brewery.

However, he did permit the creation of several animated cartoons, an art form in which he had gained experience during World War II, and he gradually relaxed his policy as he aged.

From 1972 to 1983, Geisel wrote six animated specials that were produced by DePatie-Freleng: The Lorax (1972); Dr. Seuss on the Loose (1973); The Hoober-Bloob Highway (1975); Halloween Is Grinch Night (1977); Pontoffel Pock, Where Are You?

Audrey approved a live-action feature-film version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas starring Jim Carrey, as well as a Seuss-themed Broadway musical called Seussical, and both premiered in 2000.