Dragon king theory

[1][2][3] The dragon king theory was developed by Didier Sornette, who hypothesizes that many crises are in fact DKs rather than black swans, i.e., they may be predictable to some degree.

Given the importance of crises to the long-term organization of a variety of systems, the DK theory urges that special attention be given to the study and monitoring of extremes, and that a dynamic view be taken.

The black swan concept is important and poses a valid criticism of people, firms, and societies that are irresponsible in the sense that they are overly confident in their ability to anticipate and manage risk.

An analysis of the precise definition of a black swan in a risk management context was written by professor Terje Aven.

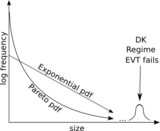

[8][9][10] Furthermore, from extreme value theory, it is known that a broad range of distributions (the Frechet class) have tails that are asymptotically power law.

[7][13] Physically speaking, dragon kings may be associated with the regime changes, bifurcations, and tipping points of complex out-of-equilibrium systems.

[1] For instance, the catastrophe (fold bifurcation) of the global ecology illustrated in the figure could be considered to be a dragon king: Many observers would be surprised by such a dramatic change of state.

The role of positive feedback loops in dragon king formation is well documented, particularly in oscillatory and cascading networks.

[16] Attractor bubbling is a generic behavior appearing in networks of coupled oscillators where the system typically orbits in an invariant manifold with a chaotic attractor (where the peak trajectories are low), but is intermittently pushed (by noise) into a region where orbits are locally repelled from the invariant manifold (where the peak trajectories are large).

Quantitative easing programs and low interest rate policies are common, with the intention of avoiding recessions, promoting growth, etc.

However, such programs build instability by increasing income inequality, keeping weak firms alive, and inflating asset bubbles.

[18][19] Ultimately such policies, aimed at smoothing out economic fluctuations, will enable an enormous correction—a dragon king.

As discussed in the previous section, dragon kings often arise in systems where other events follow a power law distribution.

Many systems exhibiting dragon kings alongside power laws can be understood by how their dynamics differ from pure SOC.

If this phase transition is first-order (discontinuous), it produces hysteresis, leading to large dragon king events.

[25][26] Even continuous transitions, which typically result in SOC, can enter regimes that produce dragon kings, depending on the nuances of the driving and dissipation.

The latter follows from the Pickands–Balkema–de Haan theorem of extreme value theory which states that a wide range of distributions asymptotically (above high thresholds) have exponential or power law tails.

However, the common approach will require continuous monitoring of the focal system and comparing measurements with a (non-linear or complex) dynamic model.

[28] For instance, in non-linear systems with phase transitions at a critical point, it is well known that a window of predictability occurs in the neighborhood of the critical point due to precursory signs: the system recovers more slowly from perturbations, autocorrelation changes, variance increases, spatial coherence increases, etc.

[30][31] These properties have been used for prediction in many applications ranging from changes in the bio-sphere[14] to rupture of pressure tanks on the Ariane rocket.

[32] The applications to a wide rage of phenomena have stimulated the complex systems perspective, which is a trans-disciplinary approach and do not depend on the first-principles understanding.

In systems that are discrete scale invariant such a model is power law growth, decorated with a log-periodic function.

This has been applied to many problems,[3] for instance: rupture in materials,[32][36] earthquakes,[37] and the growth and burst of bubbles in financial markets[12][38][39][40][41] An interesting dynamic to consider, that may reveal the development of a block-buster success, is epidemic phenomena: e.g., the spread of plague, viral phenomena in media, the spread of panic and volatility in stock markets, etc.

In the simplest case, one performs a binary classification: predicting that a dragon king will occur in a future interval if its probability of occurrence is high enough, with sufficient certainty.

In this dynamic setting, the test will likely be weak most of the time (e.g., when the system is around equilibrium), but as one approaches a dragon king, and precursors become visible, the true positive rate should increase.

Some statistical examples of the effect of extremes are that: the largest nuclear power plant accident (Chernobyl disaster) had a roughly equal damage cost(as measured by estimated US dollar cost) as all (+- 175) other historical nuclear accidents together,[44] the largest 10 percent of private data breaches from organizations accounts for 99 percent of the total breached private information,[45] the largest five epidemics since 1900 caused 20 times the fatalities of the remaining 1363,[7][46] etc.

Despite the importance of extreme events, due to ignorance, misaligned incentives, and cognitive biases, there is often a failure to adequately anticipate them.

Technically speaking, this leads to poorly specified models where distributions that are not heavy-tailed enough, and under-appreciate both serial and multivariate dependence of extreme events.

Some examples of such failures in risk assessment include the use of Gaussian models in finance (Black–Scholes, the Gaussian copula, LTCM), the use of Gaussian processes and linear wave theory failing to predict the occurrence of rogue waves, the failure of economic models in general to predict the financial crisis of 2007–2008, and the under-appreciation of external events, cascades, and nonlinear effects in probabilistic risk assessment, leading to not anticipating the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011.

To provide such risk characterizations, the dynamic dragon kings must be reasoned about in terms of annual frequency and severity statistics.

A: City sizes

B: Inoculation model [ 21 ]

C: Complex contagion model [ 21 ]

D: Quasicritical neuronal models [ 22 ] , rice-pile [ 23 ]

E: BTW–Kuramoto [ 15 ] , Facilitated sandpile [ 24 ]