Drexel Burnham Lambert

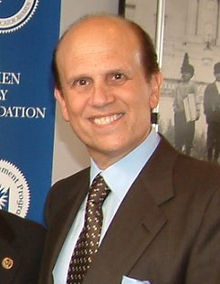

Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc. was an American multinational investment bank that was forced into bankruptcy in 1990 due to its involvement in illegal activities in the junk bond market, driven by senior executive Michael Milken.

Milken, who was Drexel's head of high-yield securities, was paid $295 million, the highest salary that an employee in the modern history of the world had ever received.

Milken and his colleagues at the high-yield bond department believed the securities laws hindered the free flow of trade.

Eventually, Drexel's excessive ambition led it to abuse the junk bond market and become involved in insider trading.

[8] Burnham started the firm with $100,000 of capital (equivalent to $1.7 million in 2023), $96,000 of which was borrowed from his grandfather Isaac Wolfe Bernheim, the founder of a Kentucky distillery.

A strict unwritten set of rules assured the dominance of a few large firms by controlling the order in which their names appeared in advertisements for an underwriting.

Michael Milken, one of the few senior executives who was a holdover from the old Drexel, got most of the credit by almost single-handedly creating a junk bond market.

Shortly after buying the old Drexel, Burnham found out that Joseph, chief operating officer of Shearson Hamill, wanted to get back into the nuts and bolts of investment banking and hired him as co-head of corporate finance.

While Milken was clearly the most powerful man in the firm (to the point that a business consultant warned Drexel that it was a "one-product company"),[3] it was Joseph who succeeded Linton as president in 1984, adding the post of CEO in 1985.

Milken himself viewed the securities laws, rules and regulations with some degree of contempt, feeling they hindered the free flow of trade.

He was under nearly constant scrutiny from the Securities and Exchange Commission from 1979 onward, in part because he often condoned unethical and illegal behavior by his colleagues at Drexel's operation in Beverly Hills.

Largely based on information Boesky promised to provide about his dealings with Milken, the SEC initiated an investigation of Drexel on November 17.

Two days later, Rudy Giuliani, then the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, launched his own investigation.

[1] A year later, Martin Siegel, the co-head of M&A, pleaded guilty to sharing inside information with Boesky during his tenure at Kidder, Peabody.

[10] For two years, Drexel steadfastly denied any wrongdoing, claiming that the criminal and SEC investigations into Milken's activities were based almost entirely on the statements of Boesky, an admitted felon looking to reduce his sentence.

Around the same year, Giuliani began seriously considering indicting Drexel under the powerful Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act.

This provision was put in the law because organized crime had a habit of absconding with the funds of indicted companies, and the writers of RICO wanted to make sure there was something to seize or forfeit in the event of a guilty verdict.

Senior Drexel executives became particularly nervous after Princeton Newport Partners, a small investment partnership, was forced to close its doors in the summer of 1988.

Princeton Newport had been indicted under RICO, and the prospect of having to post a huge performance bond forced its shutdown well before the trial.

[1][10] Nonetheless, negotiations for a possible plea agreement collapsed on December 19 when Giuliani made several demands that were far too draconian even for those who advocated a settlement.

Giuliani demanded that Drexel waive its attorney–client privilege, and also wanted the right to arbitrarily decide that the firm had violated the terms of any plea agreement.

[1][10] Only two days later, however, Drexel lawyers found out about a limited partnership set up by Milken's department, MacPherson Partners, they previously hadn't known about.

[13][14] The government had dropped several of the demands that had initially angered Drexel but continued to insist that Milken leave the firm if indicted—which he did shortly after his own indictment in March 1989.

[10] Drexel's Alford plea allowed the firm to maintain its innocence while acknowledging that it was "not in a position to dispute the allegations" made by the government.

[15] Due to several deals that did not work out, as well as an unexpected crash of the junk bond market, 1989 was a difficult year for Drexel even after it settled the criminal and SEC cases.

Reports of an $86 million loss going into the fourth quarter resulted in the firm's commercial paper rating being cut in late November.

Groupe Bruxelles Lambert refused even to consider making an equity investment until Joseph improved the bottom line.

The filing covered only the parent company, not the broker/dealer; executives and lawyers believed that confidence in Drexel had deteriorated so much that the firm was finished in its then-current form.

[16] Richard A. Brenner, the brother of a president with controlling stakes stated in his memoir My Life Seen Through Our Eyes that other firms at Wall Street did not support Drexel or come to its aid when the company got into trouble because they were "smelling an opportunity to grab this business".

[17] By the late 1980s, public confidence in leveraged buyouts had waned, and criticism of the perceived engine of the takeover movement, the junk bond, had increased.