Du "Cubisme"

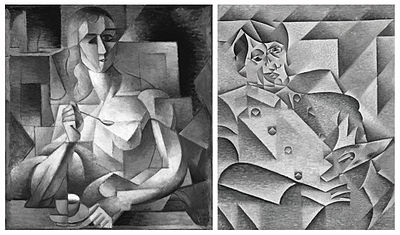

The book is illustrated with black and white photographs of works by Paul Cézanne (1), Gleizes (5), Metzinger (5), Fernand Léger (5), Juan Gris (1), Francis Picabia (2), Marcel Duchamp (2), Pablo Picasso (1), Georges Braque (1), André Derain (1), and Marie Laurencin (2).

Prior to publication the book was announced in the Revue d'Europe et d'Amérique, March 1912; for the occasion of the Salon de Indépendants during the spring of 1912 in the Gazette des beaux-arts;[1] and in Paris-Journal, October 26, 1912.

[2][3] It was subsequently published in English and Russian in 1913; a translation and analysis in the latter language by the artist, theorist and musician Mikhail Matiushin appeared in the March 1913 issue of Union of the Youth,[4] where the text was quite influential.

[5][6][7] The collaboration between Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger that would lead to the publication of Du "Cubisme" began during the aftermath of the 1910 Salon d'Automne.

In a review of the 1910 Salon d'Automne the poet Roger Allard (1885-1961) announced the appearance of a new school of French painters who—in contrast with Les Fauves and Neo-Impressionists—concentrated their attention on form rather than on color.

[8] But it was Metzinger, a Montmartrois in close contact with Le Bateau-Lavoir and its habitués—including Guillaume Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Maurice Princet, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque—who introduced to Gleizes and the others of the group, with his Nu à la cheminée (Nu), 1910, an extreme species of 'analytic' Cubism (a term that would emerge years later to describe the 1910–1911 works of Picasso and Braque).

A few months later, during the spring of 1911 at the Salon des Indépendants, the term "Cubisme" (derived by critics' attempts to derogatorily ridicule the "geometrical follies" that gave a "cubic" appearance to their work) would officially be introduced to the public in relation to these artists exhibiting in the 'Salle 41', which included Gleizes, Metzinger, Le Fauconnier, Léger, and Delaunay (but not Picasso or Braque, both absent from public exhibitions at the time resulting from a contract with the Kahnweiler gallery).

[3][9] A seminal text written by Metzinger titled Note sur la peinture, published during the fall of 1910, closely coinciding with Salon d'Automne, cites Picasso, Braque, Delaunay and Le Fauconnier as painters who were realising a 'total emancipation' ['affranchissement fondementale'] of painting.

This is the concept of "mobile perspective" that would tend towards the representation of the "total image"; a series of ideas that still today define the fundamental characteristics of Cubist art.

[11] Setting the stage for Du "Cubisme", Metzinger's Note sur la peinture not only highlighted the works of Picasso and Braque, on the one hand, Le Fauconnier and Delaunay on the other.

Gleizes and Metzinger, in preparation for the Salon de la Section d'Or, published Du "Cubisme", a major defense of Cubism, resulting in the first theoretical essay on the new movement; predating Les Peintres Cubistes, Méditations Esthétiques (The Cubist Painters, Aesthetic Meditations) by Guillaume Apollinaire (1913) and Der Weg zum Kubismus by Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1920).

In his capacity as Figuière's editorial assistant Nayral had selected for publishing Du "Cubisme" and Les Peintres Cubistes as part of a projected series on the arts.

These writers and other Symbolists valued expression and subjective experience over an objective view of the physical world, embracing an antipositivist or antirationalist perspective.

These preoccupations are in tune with Jules Romains’ theory of Unanimism, which stresses the importance of collective feelings in the breaking down of barriers between people.

[19] One major innovation made by Gleizes and Metzinger was the inclusion of the concept of simultaneity into not just the theoretical framework of Cubism, but into the physical paintings themselves.

It was in part a concept born out of a conviction based on their understanding of Henri Poincaré and Bergson that the separation or distinction between space and time should be comprehensively challenged.

[20][21] The concept of observing a subject from different points in space and time simultaneously (multiple or mobile perspective) "to seize it from several successive appearances, which fused into a single image, reconstitute in time" developed by Metzinger (in his 1911 article Cubisme et tradition[23]) and touched upon in Du "Cubisme", was not derived from Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, though it was certainly influenced in a similar way, through the work of Jules Henri Poincaré (particularly Science and Hypothesis).

If we wished to relate the space of the [Cubist] painters to geometry, we should have to refer it to the non-Euclidean mathematicians; we should have to study, at some length, certain of Riemann's theorems.

Loving light, we refuse to measure it, and we avoid the geometrical ideas of the focus and the ray, which imply the repetition-contrary to the principle of variety which guides us-of bright planes and sombre intervals in a given direction.

Loving colour, we refuse to limit it, and subdued or dazzling, fresh or muddy, we accept all the possibilities contained between the two extreme points of the spectrum, between the cold and the warm tone.

Here are a thousand tints which issue from the prism, and hasten to range themselves in the lucid region forbidden to those who are blinded by the immediate...[13]There are two methods of regarding the division of the canvas, in addition to the inequality of parts being granted as a prime condition.

This—its position on the canvas matters little—gives the painting a centre from which the gradations of colour proceed, or towards which they tend, according as the maximum or minimum of intensity resides there.

Far be it from us to throw any doubts upon the existence of the objects which strike our senses; but, rationally speaking, we can only have certitude with regard to the images which they produce in the mind.

It therefore amazes us when well-meaning critics try to explain the remarkable difference between the forms attributed to nature and those of modern painting by a desire to represent things not as they appear, but as they are.

We are frankly amused to think that many a novice may perhaps pay for his too literal comprehension of the remarks of one cubist, and his faith in the existence of an Absolute Truth, by painfully juxtaposing the six faces of a cube or the two ears of a model seen in profile.

From a reciprocity of concessions arise those mixed images, which we hasten to confront with artistic creations in order to compute what they contain of the objective; that is of the purely conventional.

(2) Juan Gris , 1912, Hommage à Pablo Picasso , Art Institute of Chicago . Exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants