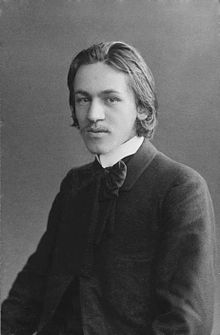

Blaise Cendrars

In 1995, the Bulgarian poet Kiril Kadiiski claimed to have found one of the Russian translations in Sofia, but the authenticity of the document remains contested on the grounds of factual, typographic, orthographic, and stylistic analysis.

In many ways, he was a direct heir of Rimbaud, a visionary rather than what the French call un homme de lettres ("a man of letters"), a term that for him was predicated on a separation of intellect and life.

Like Rimbaud, who writes in "The Alchemy of the Word" in A Season in Hell, "I liked absurd paintings over door panels, stage sets, backdrops for acrobats, signs, popular engravings, old-fashioned literature, church Latin, erotic books full of misspellings," Cendrars similarly says of himself in Der Sturm (1913), "I like legends, dialects, mistakes of language, detective novels, the flesh of girls, the sun, the Eiffel Tower.

He was drawn to this same immersion in Balzac's flood of novels on 19th-century French society and in Casanova's travels and adventures through 18th-century Europe, which he set down in dozens of volumes of memoirs that Cendrars considered "the true Encyclopedia of the eighteenth century, filled with life as they are, unlike Diderot's, and the work of a single man, who was neither an ideologue nor a theoretician".

He became acquainted with the international array of artists and writers in Paris, such as Chagall, Léger, Survage, Suter, Modigliani, Csaky, Archipenko, Jean Hugo and Robert Delaunay.

Cendrars's style was based on photographic impressions, cinematic effects of montage and rapid changes of imagery, and scenes of great emotional force, often with the power of a hallucination.

These qualities, which also inform his prose, are already evident in Easter in New York and in his best known and even longer poem The Transsiberian, with its scenes of revolution and the Far East in flames in the Russo-Japanese war ("The earth stretches elongated and snaps back like an accordion / tortured by a sadic hand / In the rips in the sky insane locomotives / Take flight / In the gaps / Whirling wheels mouths voices / And the dogs of disaster howling at our heels").

[13] Cendrars became an important part of the artistic community in Montparnasse; his writings were considered a literary epic of the modern adventurer.

He was acquainted with Ernest Hemingway, who mentions having seen him "with his broken boxer's nose and his pinned-up empty sleeve, rolling a cigarette with his one good hand", at the Closerie des Lilas in Paris.

[19] Cendrars's departure from poetry in the 1920s roughly coincided with his break from the world of the French intellectuals, summed up in his Farewell to Painters (1926) and the last section of L'homme foudroyé (1944), after which he began to make numerous trips to South America ("while others were going to Moscow", as he writes in that chapter).

It was during this second half of his career that he began to concentrate on novels, short stories, and, near the end and just after World War II, on his magnificent poetic-autobiographical tetralogy, beginning with L'homme foudroyé.

[20] He was with the British Expeditionary Force in northern France at the beginning of the German invasion in 1940, and his book that immediately followed, Chez l'armée anglaise (With the English Army), was seized before publication by the Gestapo, which sought him out and sacked his library in his country home, while he fled into hiding in Aix-en-Provence.

He comments on the trampling of his library and temporary "extinction of my personality" at the beginning of L'homme foudroyé (in the double sense of "the man who was blown away").

Details of his time with the BEF and last meeting with his son appear in his work of 1949 Le lotissement du ciel (translated simply as Sky).

They had three children: Rémy (an airman killed in WW2), Odilon and Miriam Gilou-Cendrars who was active with the Free French in London during World War II.