Dual Contracts

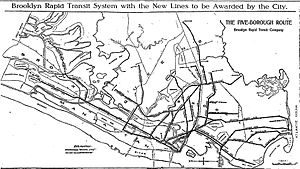

As part of the Dual Contracts, the IRT and BRT would build or upgrade several subway lines in New York City, then operate them for 49 years.

Both the IRT and BRT (later Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation, or BMT) worked together to make the construction of the Dual Contracts possible.

[2] Living in Manhattan was becoming a hazard due to the higher probability of crime and overcrowding, and for the most part, the first subway line only served areas that were already developed.

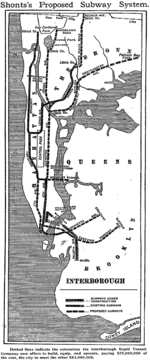

Although the PSC had created ambitious plans for the expansion of the city's subway system, they only had $200 million on hand.

[5] In 1911, George McAneny was appointed leader of the Transit Committee of the New York City Board of Estimate, which oversaw the subway expansion plans.

[6] Some opposed the Dual Contracts as they thought that the company owners and city officials were just looking for another way to produce personal revenue.

This would lower population densities in the city and also made as a good reason to help prove the subway expansion as necessary.

During the year ended June 30, 1911, shortly after which the construction of the new system was begun, the existing rapid transit lines carried 798,281,850 passengers.

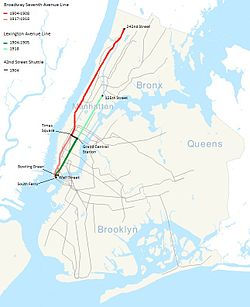

The system had four tracks between Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall and 96th Street, allowing for local and express service on that portion.

The city's third major rapid transit company, the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (now PATH), was excluded from the contracts.

The IRT would access the station from both the 1907 Steinway Tunnel and an extension of the Second Avenue Elevated from Manhattan over the Queensboro Bridge.

Technically the line was under IRT "ownership", but the BRT/BMT was granted trackage rights in perpetuity, essentially making it theirs also.

This came to be important when service was extended for the 1939 World's Fair, as the IRT was able to offer direct express trains from Manhattan, and the BRT was not.

To facilitate this arrangement originally, extra long platforms were constructed along both Queens routes, so separate fare controls/boarding areas could be established.

[13] Several provisions were imposed on the companies, which eventually led to their downfall and consolidation into city ownership in 1940: There were other conditions in regards to specific operations of the lines, as part of a deal between the IRT, the BMT, and the Public Service Commission.

The census resulted in the following: People were allowed to move to better parts the same cost and could have a better and more comfortable life in the suburbs.